Abstract Expressionism January - June 1948

by Gary Comenas

Arshile Gorky: "You don't recognize it when you are looking for it, and you won't recognize it by looking in a magazine. It's right here in the moon, the stars, the horizon, the snow formations, the first patch of brown earth under the poplar. In this house we can see all those things. But what I miss are the songs in the fields. No one sings them any more because every one has become a little business man."

1948: Franz Kline is listed in Who's Who in the East (Volume 2).

(FK178)

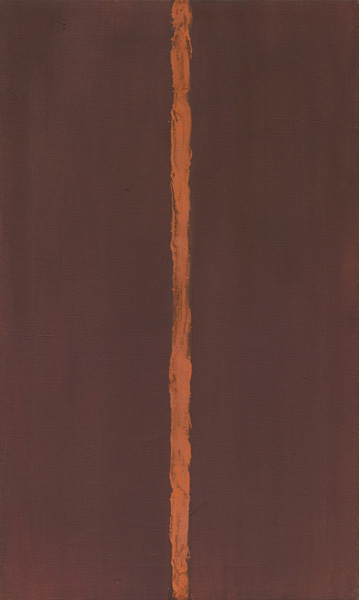

1948: Barnett Newman begins painting his "zip" paintings. (RO255)

Onement 1 (1948), Barnett Newman, Oil and painted masking tape on canvas, 27 1/4 x 16 1/4", © 2016 Barnett Newman Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, Museum of Modern Art, New York

The first was Onement I (1948). (RO255) The next two years would be the most productive of Newman's career. (MH)

Ned Denny [from "Nothing to It: Ned Denny Discovers Great Depths and Subtleties in Emptiness," New Statesman (October 7, 2002)]:

His [Barnett Newman's] paintings can seem to be barely doing anything at all, and yet, given time and attention, they reveal depths and subtleties of immense power. Their emptiness isn't the dumb, blank emptiness that comes from the feeling that there's nothing worth saying, but one charged with unfashionable notions of sacredness and mystery.... This much is clear from some of Newman's earliest surviving works (he resumed painting at the age of 40 after a long hiatus and destroyed all his previous efforts), a series of ink drawings that evoke a primal, blinding light. One shows what looks like a sun with a blazing halo of black, brushy strokes, but most are sliced by the stripe or ray or "zip" he would become indelibly associated with. What's easy to forget is that the searing whiteness we see in the sun and the rays is merely that of the paper, raised by Newman's brushwork to an unearthly pitch.

Aside from the beautiful and remarkably modern-looking The Word I (1946), in which a pale ray cuts through a desert-like zone of yellows, browns and feathery greys, the paintings of the same period are less successful. Newman chokes them with lurid, overworked textures, and the tapering, predominantly yellow beams give them the look of cheap science-fiction covers. The breakthrough comes with the famous Onement I (1948), actually a semi-worked canvas that Newman scrutinised for eight months before deciding it was complete, and from now on his "zips are allowed to breathe in clear, featureless voids. After Onement I, Newman said, he produced paintings as opposed to pictures, and you can see what he means. Works like Onement III (1949), its central, slender, flame-like column dominating yet menaced by the deep brown ground, are not in any way illustrative but purely and simply themselves. They are modest and sober and yet quietly, strangely, strong. They are serious paintings, yet without being academic or doctrinaire. They demand a response.

January 5 - 23, 1948: Jackson Pollock shows his drip paintings for the first time.

Jackson Pollock showed the new paintings at his first solo exhibition at the Betty Parsons Gallery. In addition to the drip paintings he also showed an earlier painting, Gothic (1944). Seventeen paintings were exhibited including, in addition to Gothic, the "allover" drip paintings Alchemy, Cathedral, Comet, Enchanted Forest, Full Fathom Five, Lucifer, Phosphorescence, Reflection of the Big Dipper and Sea Change. Pollock and Krasner went to New York for the show. (JP182) Works were priced as low as $150.

The reaction to Pollock's drip paintings was underwhelming. Only one painting was sold (to a friend of Guggenheim) and the press reaction was mixed. Robert Coates wrote in The New Yorker that some of the paintings have "a good deal of poetic suggestion about them" but that sometimes "communications break down entirely." The Art News review admired the use of aluminium paint and its "beautiful astronomical effects" but thought that the work suffered from "monotonous intensity." The reviewer for Art Digest, Alonso Lansford, characterized the work as "colorful and exciting" and commented that "it will be interesting to see the reactions" to the exhibition. (JP183).

Sculptor Herbert Ferber who also exhibited at the gallery asked Pollock if he could trade one of his sculptures for a painting and Pollock agreed, telling him to pick any one that he wanted. Ferber chose one of his smaller works, Vortex, later explaining "I didn't want to seem greedy." As part of the his deal with Parsons, Jackson was able to keep one of the paintings. He chose Lucifer, the largest painting in the show. He would later give it away to settle a doctor's bill. The remaining paintings were given to Peggy Guggenheim to fulfil Pollock's contractual obligations. His contract with Guggenheim would not end until three weeks after the exhibition closed. Over the next few years Guggenheim gave away all but two of the paintings to various museums.

Pollock's financial situation in the Springs became increasingly dire as a result of the lack of sales. Parsons wrote to Guggenheim on February 26th, "I hope he [Pollock] will be able to go on painting: his finances seem very precarious." On April 5, 1948 she wrote again to Guggenheim: "I am still very worried about the terrible financial condition of the Pollocks." (JP183) Parsons lent Jackson and Lee a few hundred dollars. Their grocer let them settle a $60 debt with a small untitled drip painting. Although the grocers' other customers laughed at the work and a rumour was started that Pollock painted with a broom, about ten years later the grocer sold the same painting for $17,000 and bought a small airplane with the money. (JP184)

January 31 - March 21, 1948: "Annual Exhibition of Contemporary American Sculptures, Watercolors and Drawings" at the Whitney Museum of American Art.

Arshile Gorky's The Betrothal is included. (BA552)

January 1948: Arshile Gorky negotiates with Julien Levy. (MS339)

Agnes wrote to Wolf Schwabacher on January 15, 1948 that Julien had agreed to Gorky getting an extra $25 a month but when Gorky had pointed out that $25 was just enough to cover the increased price of art materials Julien agreed to a $50 increase but wanted more paintings. (MS339)

January 1948: Clement Greenberg discusses "The Situation at the Moment" in Partisan Review.

Although no mention of Existentialism was made in his essay, Greenberg couched his argument in terms akin to Existentialism. For Greenberg there was "no use in deceiving ourselves with hope." Isolation and alienation was "the condition under which the true reality of our age" was experienced.

From "The Situation at the Moment" (1948) [repr. in Clement Greenberg: The Collected Essays and Criticism, Volume 2: Arrogant Purpose, 1945-1949]:

To define the exact status of contemporary American art in relation to the history of art past and present demands a certain amount of mercilessness and pessimism. Without these we shall not know where we are at. There is no use in deceiving ourselves with hope... As dark as the situation still is for us, American painting in its most advanced aspects - that is, American abstract painting - has in the last several years shown here and there a capacity for fresh content that does not seem to be matched either in France or Great Britain... The American artist has to embrace and content himself, almost, with isolation, if he is to give the most of honesty, seriousness, and ambition to his work. Isolation is, so to speak, the natural condition of high art in America.

Yet it is precisely our more intimate and habitual acquaintance with isolation that gives us our advantage at this moment. Isolation, or rather the alienation that is its cause, is the truth - isolation, alienation, naked and revealed unto itself, is the condition under which the true reality of our age is experienced. And the experience of this true reality is indispensable to any ambitious art. (CG192-3)

According to Greenberg "abstract painting, being flat, needs a greater extension of surface" and becomes "trivial when confined within anything measuring less than two feet by two." Works of art had to be big to be meaningful. Size mattered for the Abstract Expressionists. (See also 1941: Richard Pousette-Dart paints Symphony No. 1, the Transcendental.)

Clement Greenberg [from "The Situation at the Moment"]:

There is a persistent urge, as persistent as it is largely unconscious, to go beyond the cabinet picture, which is destined to occupy only a spot on the wall, to a kind of picture that, without actually becoming identified with the wall like a mural, would spread over it and acknowledge its physical reality... it is a fact that abstract painting shows a greater and greater reluctance for the small, frame-enclosed format. Abstract painting, being flat, needs a greater extension of surface on which to develop its ideas than does the old three-dimensional easel painting, and it seems to become trivial when confined within anything measuring less than two feet by two. (CG195)

January 1948: The U.S. Senate passes the Smith-Mundt Act.

From How New York Stole the Idea of Modern Art

by Serge Guilbaut:

In 1946 and 1947 certain members of Congress traveled to Europe and came back quite surprised by their reception and by the bad press the United States received overseas. To counter what American observers took to be the results of an adroit Communist propaganda campaign, the Senate passed the Smith-Mundt Act in January 1948, reorganizing and expanding the Information and Cultural Program. The act directed attention to the problem of presenting a clear and accurate image of the United States: 'If other people understood us, they would like us, and if they liked us, they would do what we wanted them to do...'

Improving the cultural image of the United States was identified in 1948 as the most important goal for American propaganda. But what sort of image was appropriate?... In 1949 Pollock became the looked-for culture hero big enough to gather something like a school around him. He was the catalyst, the 'ice-breaker' of the new American avant-garde. (SG192-4)

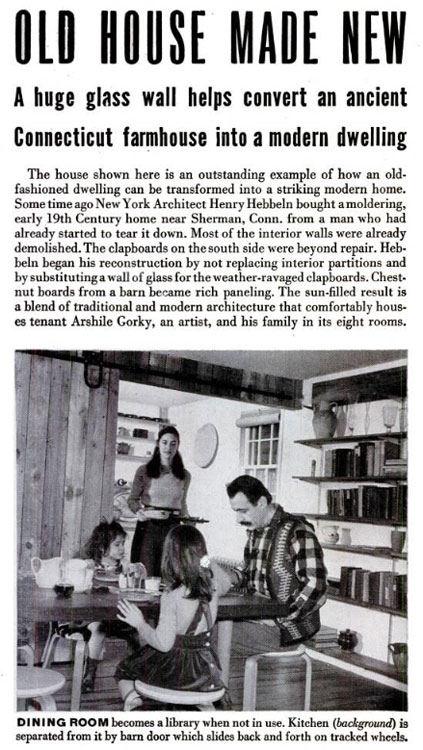

February 9, 1948: Arshile Gorky appears in the Waterbury Sunday Republican. (MS398)

Although Gorky biographer Matthew Spender wrote in his biography of the artist, From a High Place: A Life of Arshile Gorky, that Gorky's friend and neighbour Alexander ("Sandy") Calder sent a local reporter around to the Hebbeln house to interview Gorky after seeing a LIfe magazine article on the house which featured Gorky, the LIfe magazine article actually came out a week after the local reporter's article appeared in the Waterbury Sunday Republican. (MS398n341/342) The Life article, "Old House Made New" appeared in the February 16th issue while the local reporter's article, ""Modern Wall Applied to Old Sherman Farmhouse Interests Builders but Its Most Interesting Feature Is Its Tenant, Arshile Gorky with His Fresh Ideas About Art" had appeared in the February 9th issue of the Sunday Republican. The Gorkys were aware that the Life article would focus on the actual house rather than on Gorky. In a letter to Wolf Schwabacher dated January 15, 1948, Gorky's wife Agnes ("Mougouch") wrote, "Life magazine is underfoot today and tomorrow - They are doing the house & how we live in it - any plugs for Gorky will be purely incidental." (MS339)

Gorky invented a past for the local reporter as he had done in previous interviews and statements, telling him that he had been born in Russia (but preferred to describe himself as an "early American") and that he had been to Brown University (which he hadn't).

Arshile Gorky [in the Waterbury Sunday Republican]:

You don't recognize it [beauty] when you are looking for it, and you won't recognize it by looking in a magazine. It's right here in the moon, the stars, the horizon, the snow formations, the first patch of brown earth under the poplar. In this house we can see all those things. But what I miss are the songs in the fields. No one sings them any more because every one has become a little business man. And there are no more plows. I love a plow more than anything else on a farm. (MS342)

February 16, 1948: Arshile Gorky appears in Life magazine. (MS398)

Although the Life article, "Old House Made New" focused on the Hebbeln house and its renovation, it included photographs of Gorky in the house. Not long after the article appeared Gorky ran into Barnett Newman at a party given by Matta.

Excerpt from the Life magazine article that included a photograph of Arshile Gorky

Barnett Newman:

...I said, "I was glad to see you as the first American artist to be featured in Life magazine.: This had never happened before to that extent... And he said, "Yes, but didn't I look sad? Didn't I look unhappy?" So I said, "Well, I really didn't notice that. I thought you looked sort of quiet." And then Gorky said, "To hell with Life magazine. The important thing is life! What interests me is my two daughters and not all this nonsense about the art world." And so we had quite an animated conversation in relation to certain [concepts] where we definitely agreed. And then Gorky got light-veined. I don't remember exactly how it came up. I may have asked him indirectly. "You know how I came to this country?" Gorky said. And he told this sarcastic story which I have a feeling he made up on the spot. "Well, when I was a young boy in Armenia, my mother used to take me to church. And every time I went to church, I was always struck by the fact that the devils were all black and the angels were all blonde. Then later I heard that in the United States, all the girls are blonde. So I figured they were angels. So I came to this country." So we had a kind of a very good time. And I thought the story was fantastic. What a man. (HH558)

February 16, 1948: Boston's Institute of Modern Art becomes the Institute of Contemporary Art.

From Jackson Pollock: A Biography by Deborah Solomon:

Resistance to his [Pollock's] art had been mounting steadily ever since his Parsons show [of his drip paintings] had closed. In February 1949 James Plaut, the director of the Institute of Modern Art in Boston, announced that the museum was changing the 'modern' in its name to 'contemporary' to disassociate itself from certain modern painters whose work signaled 'a cult of bewilderment.' The museum statement did not mention any artists by name, although a follow-up story in The New York Times specified that the name change in Boston represented a necessary effort to distinguish the 'experimental meanderings' of such artists as Pollock and Gorky from art that possessed meaning. That May a group of artists headed by the painter Paul Burlin planned a well- publicized protest meeting at the Museum of Modern Art to oppose the name change in Boston, and while Pollock was not among the thirty-six official organizers, he and Lee both attended." (JP186-7)

February 25, 1948: Communists seize power in Czechoslovakia.

Jan Rychlik [Czechoslovakian historian - author of Cesi a Slovaci ve 20. stoleti:

What happened was a crisis of the government when ministers of three coalition parties: the National Socialist Party, the People's Party and the Slovak Democratic Party, submitted their resignations. This happened because the Communist Minister of the Interior Vaclav Nosek refused to re-hire some police officers who were dismissed for political reasons. When these ministers resigned, the Communists called for massive rallies and forced President Benes to accept their resignation and to appoint a new government which in fact was a government under the total domination of the Communist Party... Military forces were not involved. But, despite the fact that the coup was bloodless and carried out in a peaceful way - it should be noted that the Communists had strong support among a substantial part of the officers and of the staff. This meant that if President Benes didn't agree to appoint the new government, the army wouldn't support him, and he would remain without any real power, because the police were already totally in the hands of the Communists. So the army was behind the scenes, ready to act if necessary. It was not involved, but if the coup had not gone along the lines prescribed by the Communists, it probably would have intervened.

February 29 - March 20, 1948: Arshile Gorky's final solo exhibition at the Julien Levy Gallery. (MA311)

Only one work was sold from the exhibition - Soft Night - which went for $700. Levy sold only nine works by Gorky during the time he was with the gallery. Most were sold to friends of Gorky - two to Jeanne Reynal, one to Gorky's ex-student and early patron Ethel Schwabacher, one to Mina Metzger (another ex-student) and one to Gorky's neighbours in Connecticut, Yves and Kay Tanguy. Levy also sold a Gorky painting to his [Levy's] father which Levy apparently forgot about as two years later it was returned to a group of unsold works. (MS345)

Gorky wasn't happy with Levy's effort - or lack of effort. During one visit to the gallery he was upset to see that his drawings had been left on the floor and one of Levy's assistants were stepping on top of them. (MS345)

Gorky and his wife attended the opening of the show and stayed at Jeanne Reynal's new house on Eleventh Street while in New York. Reynal held a party where one main topic of conversation being the activities of the Surrealists in Paris. Arshile and Agnes also had lunch with the Schwabachers. Ethel Schwabacher told Gorky she wanted to write a book about him. He approved of the idea and asked her if she had read Robert Melville's book on Picasso and whether she could use it as a model for her own book. She suggested that they meet up again so that she could record what he said about art. Although they would meet up again, Schwabacher never got a chance to record Gorky's views on art although she would later publish the first biography of the artist. (MS343)

Clement Greenberg reviewed Gorky's show in the March 20th issue of The Nation.

Clement Greenberg [from his review in The Nation]:

What is new about these paintings is the unproblematic voluptuousness with which they celebrate and display the processes of painting for their own sake. With this sensuous richness, which is a refined product of assimilated French tradition, and his own personality as an artist, with all its strengths and weaknesses. Gorky at last arrives at himself and takes his place - awaiting him now for almost twenty years - among the very few contemporary American paints whose work is of more than national importance...

Gorky owes something to Matta's drawing, but he has exalted this ingredient, developing it with a plenitude of painterly qualities such as Matta himself appears incapable of. And he also owes something to Miro - but why not? Gorky's method is what the French call tachisme - 'spotting,' the adjustment of spots or isolated areas of color, usually against a more or less uniform background. Matisse is a tachiste, and so was Bonnard to some extent, but the source of the method as Gorky practices it is Miro, and it is because Miro is still so relatively new that Gorky appears to imitate him; in the time impression will fade...

Gorky's forte is his draftmanship, and his color is rather confined in its range and effect. Usually he keeps to one of two scales - black, blue, gray, white; or vermilion, red, rose, tan, ocher. In his two strongest pictures - The Calendars and Agony - the hotter scale is largely relied upon; in another, Soft Night, which is perhaps the most interesting and promising if not quite the best picture present, the register is black, gray, and white. But yellow is predominant in the excellent Pastoral, which is washed in like a water color... Also to be noticed is the orange and tan Plow and the Song. Gorky tends to favour horizontal or square formats, but he changes to the vertical in two impressive but uneven pictures, Betrothal I and Betrothal II, which are similar in their general tonality and linearism...

The presence of six pictures as excellent as those named about in a show comprising some fifteen or sixteen items in all declares a remarkable rate of performance, especially in view of the very high level the artist sets himself. And Gorky in my opinion, has still to paint his greatest pictures... (CG219-21)

Gorky never went on to, as Greenberg put it, "paint his greatest pictures." By the end of of the year he was dead.

March 1948: Mark Rothko's second show at the Betty Parsons Gallery.

Included were Phalanx of the Mind, Beginnings, Intimations of Chaos, Sacred Vessel, Dream Memory, Ceremonial Vessel, Aeolian Harp, Vernal Memory, Geologic Memory, Poised Elements, Gethsemane, Agitation of the Archaic, Dance and Companionship and Solitude. (RO232) (Gethsemane was priced at $550 at Rothko's Art of the Century exhibition in 1945. The price was raised to $750 for the Parson's exhibition.) (RO252)) No works were sold. However, according to records kept by the Betty Parsons Gallery, Rothko did sell at least six other works that year (Number 10, 1948 ($400), Number 23, 1948 ($250) and Number 24, 1948 ($250), an unidentified gouache ($125), Votive Mood ($150), and an unidentified watercolour ($250). One list kept by the gallery of sold works includes three Rothko watercolours dated 1948 but does not indicate the price or date of sale. (RO609fn50)

March 1948: "The Decline of Cubism" by Clement Greenberg appears in Partisan Review no 3 (1948).

The article was accompanied by reproductions of two paintings by Gorky - The Betrothal I (1947) and Agony (1947).

At a time when many American abstract artists had already progressed from Cubism to Surrealism to full abstraction (while often retaining elements of all three styles), Greenberg defended Cubism as being "still the only vital style of our time, the one best able to convey contemporary feeling, and the only one capable of supporting a tradition which will survive into the future and form new artists." (CG213) But Cubism was on the wane as the political environment it grew up in changed.

Clement Greenberg [from "The Decline of Cubism"]:

Cubism originated not only from the art that preceeded it, but also from a complex of attitudes that embodied the optimism, boldness, and self-confidence of the highest stage of industrial capitalism... Cubism, by its rejection of illusionist effects in painting or sculpture and its insistence on the physical nature of the two-dimensional picture plane... expressed the positivist or empirical state of mind with its refusal to refer to anything outside the concrete experience of the particular discipline, field or medium in which one worked; and it also epressed the empiricists's faith in the supreme reality of concrete experience. Along with this... went an all-pervasive conviction that the world would inevitably go on improving...

Cubism reached its height during the First World War and, though the optimism on which it unconsciously floated was draining away fast, during the twenties it was still capable, not only of masterpieces from the hands of Picasso, Braque, Léger, but also of sending forth such bold innovators as Arp, Mondrian, and Giacometti, not to mention Miró. But in the early thirties... the social, emotional and intellectual substructure of cubism began crumbling fast. Even Klee fell off after 1930. Surrealism and neo-romanticism... sprang up to compete for attention... After 1939 the cubist heritage entered what would seem the final stage of its decline in Europe... In a world filled with nostalgia and too profoundly frightened by what has just happened to dare hope that the future contains anything better than the past, how can art be expected to hold on to advanced positions? (CG214)

Greenberg associates the rise of Cubism with the "highest stage of industrial capitalism" but does not fully explain the reasons for its decline, although he seems to be inferring it had something to do with the second World War and the political and economic upheavals leading up to it. The end result of the decline of artists "as great as Picasso, Braque and Léger" was the migration of "the main premises of Western art" to the United States "along with the center of gravity of industrial production and political power." (CG215)

Clement Greenberg [from "The Decline of Cubism"]:

Obviously, the present situation of art contains many paradoxes and contradictions that only time will resolve. Prominent among them is the situation of art in this country. If artists as great as Picasso, Braque, and Léger have declined so grievously, it can only be because the general social premises that used to guarantee their functioning have disappeared in Europe. And when one sees, on the other hand, how much the level of American Art has risen in the last five years, with the emergence of new talents so full of energy and content as Arshile Gorky, Jackson Pollock, David Smith... then the conclusion forces itself, much to our own surprise, that the main premises of Western art have at last migrated to the United States, along with the center of gravity of industrial production and political power. (CG215)

One could deduce from Greenberg's statements that artistic movements follow the "center of gravity of industrial production" ie Capitalism and that Capitalism, therefore, is a positive force on aesthetics. But I doubt if Greenberg, who has been described as a "cultural Trotskyite," would agree.

March 20, 1948: Clyfford Still tells Betty Parsons not to show his art to the public.

In a letter to Parsons dated March 20th, Still wrote, "Please - and this is important, show only to those who may have some insight into the values involved, and allow no one to write about them. NO ONE... And I no longer want them shown to the public at large, either singly or in group." (SG201)

c. March 1948: Arshile Gorky's wife's Great-Aunt Marion Hosmer dies. (HH560)

Not long before dying Aunt Marion told Mougouch that if she didn't come soon to see her it might be too late. Gorky refused to let Agnes go and Marion died without seeing Mougouch for a final time. (HH560)

End March 1948: Ethel Schwabacher visits the Gorkys at the Hebbeln house in Sherman, Connecticut.

Ethel accompanied Arshile and Agnes ["Mougouch"] back to Sherman from one of their regular trips to New York. In Sherman Gorky showed Ethel a work that would be titled Dark Green Painting after his death. (MS346)

While living in Sherman, Gorky made trips to New York every six weeks for a check-up with Dr. Weiss but rarely discussed his condition with others. His sister Vartoosh asked one of their friends who was a doctor to speak to Dr. Weiss. Dr. Hampartsoum Kelikian (at the time the surgeon general to the U.S. Army) spoke to Weiss and concluded that there was little hope for Gorky. After Gorky's death, some family members believed that Kelikian had also told Gorky the true situation. (MS354)

April 6, 1948: The Soviet Union signs a "treaty of friendship" with Finland.

From Article 1 of the treaty:

Should either Finland, or the Soviet Union through the territory of Finland, become the object of military aggression on the part of Germany or any Power allied with Germany, Finland will carry out its duty as a sovereign State and will fight to repel aggression. In so doing, Finland will direct all the forces at its disposal towards defending the integrity of its territory on land, sea and air, acting within the limits of its boundaries, in accordance with its obligations under the present treaty, with the help, if necessary of the Soviet Union or together with the Soviet Union.

April - May 1948: Henri Matisse: Retrospective Exhibition of Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Franz Kline attended the exhibition with David Orr. (FK178)

May 10 - 29, 1948: Robert Motherwell solo exhibition at the Samuel Kootz Gallery. (RM135)

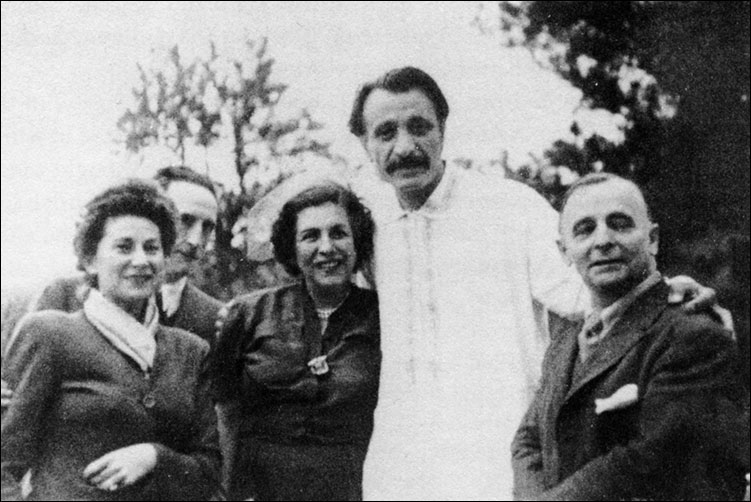

May 23, 1948: Frederick Keisler and Marcel Duchamp visit the Gorkys and Tanguys in Sherman. (MS354)

L to R: Maria Martins, Marcel Duchamp (behind Maria), Mrs. Enrico Donati, Arshile Gorky and Frederick Kiesler, Sunday 23 May 1948

Gorky's wife Agnes ("Mougouch") was visiting her parents in Virginia, leaving the children there when she returned a day or so later.

Spring 1948: Samuel Kootz gets Picasso and gives up his gallery.

Samuel Kootz gave up his gallery at 15 East 57th Street and moved his operation to an apartment at 470 Park Avenue.

Samuel Kootz:

In the spring of '48, something happened as the result of a show we had in January of '47 when we had gone to Paris to pick up a show by Picasso, and did so well with that and a couple of succeeding trips to Picasso that he suggested that my wife and I give up the public gallery and take an apartment in New York where we could show his work and also an apartment in Paris where we'd be for six months of the year, and he was to give me the names of the European collectors. This probably was so enticing to become the world agent for Picasso that we deliberately gave up the Gallery and took an apartment at 470 Park Avenue. And the whole apartment, of course, was covered by Picasso paintings. We gave this up in not too long a time for a very curious incident. We found that as a private dealer anyone who had a big dinner party and who had nothing to do with his guests would think it would be perfectly all right to bring them over to our apartment and spend the evening discussing Picasso. So that we had very little private life.

In addition to that, one of my biggest customers was Stephen Clark who had already purchased six or seven paintings from me by Picasso. And I had just received a wonderful picture by Picasso that was subsequently sold. And I wrote Mr. Clark thinking this would be just up his alley. On Saturday morning, I was sitting in my living room unshaved, my hair uncombed, in pajamas and a robe, drinking coffee and reading the morning paper when the doorbell rang. We had always suggested to the building that someone must be announced, and consequently when I went to the door I thought it was probably one of the employees of the building. But there was Mr. Clark all dandified, dressed to the hilt. He could not have been more embarrassed nor could I have been more embarrassed, and he couldn't get out fast enough. This was a picture that I knew he would have purchased under any other circumstances.

When my wife awoke at ten o'clock, I told her I had news for her; we were going back to a public gallery where anybody could enter and leave as he sees fit with no desire to give a greeting or to purchase a picture, but that we were free. At 5:30 the gallery would be closed, and we had our private life back again. (KD)

Malcolm Goldstein [from Landscape with Figures]:

Kootz had worked his way into Picasso's favor by presenting him with a copy of Harriet and Sidney Janis' Picasso: The Recent Years, 1939-46 (1946), as Kootz was pleased to tell Sidney Janis on his return. Apparently Picasso had not already seen the book. Why the Janises themselves had not given him a copy is a mystery. Persistent rumor had it that Kootz gave Picasso another, considerably more costly present: a white Cadillac, sent on to the artist in advance of their meeting as a "calling card." (FG241)

Spring 1948: Clyfford Still moves to New York.

Still moved to New York after resigning from the California School of Fine Arts. (RO263)

Spring 1948: The Sidney Janis Gallery opens.

Sidney Janis:

Writing books on art wasn't very profitable, and in the late forties I decided to come out of retirement, this time to go into a business I knew; something I really loved. After ten years of meditation and writing, I decided to open a gallery. In May of 1948 I took the space Sam Kootz had given up on Fifty-seventh Street... Our opening exhibition was given over to Léger, a show with with important paintings I had on loan from European collections. Only one was sold. We followed with one-man shows of Kandinsky, Mondrian, Schwitters, Albers - all definitive shows... We continued with exhibitions of the School of Paris, and by late 1951 began to include one-man exhibitions of important American painters. The Pollock generation was shown side by side with the Picasso generation, the acknowledged masters of Europe. Clement Greenberg later found that such juxtapositions helped the public make the transition, the very long step from Cubism and Surrealism to the New York School. (AD36-7)

Janis would eventually represent Willem de Kooning, Mark Rothko, Robert Motherwell and Adolph Gottlieb. A year after Gorky's death, Gorky's wife would also move his estate from the Julien Levy Gallery to the Janis Gallery. (DK316)

April 1948: The Marshall Plan is adopted by Congress. (SG147)

April 12, 1948: Willem de Kooning's first solo show opens at the Charles Egan Gallery.

At the age of 43 (soon to be 44) de Kooning finally had a one-man exhibition. It consisted of ten black and white paintings which Charles Egan had noticed while visiting de Kooning in his studio. Egan and de Kooning met on a regular basis. Egan's then wife, Betsy Egan Duhrssen recalled, "Charlie used to go down to Bill's studio early in the morning. Bill had a way of not letting people in when he was working. They'd take walks and talk. Charlie loved to talk about art." (DK250)

The paintings were priced from $300 - $2,000. When nothing sold during the first month, Egan extended the exhibition another month. Although the exhibition may not have been popular with the collectors, young artists flocked to it who had heard of de Kooning through other artists or from the Waldorf Cafeteria. Jane Freilicher was one of them, later saying "Bill was acclaimed from the minute he started showing... Everybody was talking about him." (DK251-2) Artist and writer Louis Finkelstein lived across from de Kooning's studio and later recalled, "There was a current of talk about him, a word of mouth. People who had missed the first Egan show were waiting for another de Kooning event." Finkelstein could see de Kooning in his studio, painting "far into the night with an air of great seriousness." (DK266-7)

Press reaction was generally favourable. Renee Arb wrote in Art News, "Here is virtuosity disguised by voluptuousness - the process of painting disguised by voluptuousness... the range of color seems as rich in black and white as in the brilliant hues." Clement Greenberg's review in The Nation referred to the show as "this magnificent first show" and de Kooning as "one of the four or five most important painters in the country." (DK252-3)

One of the paintings in the exhibition, Painting, was eventually purchased in the autumn by the Museum of Modern Art for $700. (DK265) It was the only painting sold from the exhibition. (DK266)

April 1948: Elaine de Kooning writes for Art News.

She had previously written dance pieces under the tutelage of Edwin Denby. (DK275)

April 25, 1948: Stephen Spender proclaims that Europeans "can still be swung to western culture" in The New York Times magazine.

In an article titled "We Can Win the Battle for the Mind of Europe" (and subtitled "The Europeans, Even Those Behind the Iron Curtain, Can Still Be Swung to Western Culture") in the April 25th issue of The New York Times Spender wrote "American freedom of expression in its greatest achievements has an authenticity which can win the most vital European thought today... For what is realistic today is to expect nothing of propaganda and political bludgeoning, but to take part in showing Europeans the greatest contemporary achievements of American civilization in education and culture." (SG173)

May 5, 1948: "The Modern Artist Speaks" at The Museum of Modern Art.

(AG172)

The forum was attended by 36 artists and an audience of about two hundred people, including Jackson Pollock, Stuart Davis, Adolph Gottlieb, L.K. Morris and Paul Burlin. James Johnson Sweeney also attended. (SG244fn54)

Paul Burlin [from "The Modern Artist Speaks"]

The modern artist is aware of the speculative thoughts of man, for this is not the age of tranquility. Titillating, kiss-mummy pictures are no longer acceptable. The prissy decor of the mantelpiece is finished. (SG181)

Stuart Davis took the opportunity of the forum to rail against the decision of Boston's Institute of Modern Art to rename itself the Institute of Contemporary art. Davis criticized the Institute's statement regarding the change as an attempt "to find ways and means to censor the artist, freedom of expression. In this way they have affinity with the Un-American Committee and the Moscow art purges, which from different motives seek to control creative ideas for ulterior purposes." Davis added "I do not impute political motives to these recent attackers in any sense, but their campaign lends support to all attacks against the artist's integrity. In fact, their arguments are identical in substance with those used against the artists by Moscow." (SG182)

May 10 - May 29, 1948: "Paintings and Collages by Motherwell" at the Samuel M. Kootz Gallery.

May 29 - September 30, 1948: Jackson Pollock, Arshile Gorky and Mark Rothko at the XXIV Venice Biennale.

Arshile Gorky, Theodoros Stamos, Mark Rothko and Mark Tobey were among the 79 American painters shown at the American pavilion (managed by The Museum of Modern Art) at the Venice Biennale. (SG248fn27)

Peggy Guggenheim's collection was shown in her own pavilion with six works by Jackson Pollock including Eyes in the Heat, The Moon Woman and Two. The show traveled (with an additional four Pollock paintings) to Florence in February 1949 and Rome in June 1949. Guggenheim referred to Pollock's Biennale showing the following year in a letter to Betty Parsons dated October 8, 1949: "I am glad you took on Pollock and only wish he could sell. Here in the Biennale he was considered by far the best of all the American painters." (JP186)

June 1948: Jackson Pollock gets a grant. (PP322)

Pollock, whose financial situation had become increasingly dire due to his lack of sales, was given a $1500 grant from the Eben Demarest Trust Fund to be paid in quarterly installments. James Johnson Sweeney had convinced the Fund to give Pollock the money. (JP184)

June 1948: Jackson Pollock is re-introduced to Tony Smith.

Through Betty Parsons, Jackson and Tony became reacquainted. They had known each other previously at the Art Students League. (PP322)

June 1948: "Survey of the Season" group show at the Betty Parsons Gallery. (MH)

Included Barnett Newman. (MH)