Abstract Expressionism 1975 - 1979

by Gary Comenas

"the same letter seven times"

1975

1975: Robert Motherwell retrospective at the Museo de Art Moderna in Mexico City. (HM)

1975: Kate Rothko wins her lawsuit against the Marlborough Gallery and the executors of Rothko's will.

After an 8 month trial, Surrogate Millard L. Midonick ruled that the executors (Bernard Reis, Theodoros Stamos and Morton Levine) and Frank Lloyd, owner of the Marlborough Gallery, had acted negligently and imposed damages and fines totaling $9,252,000 against the executors and gallery. The contracts entered into on May 21, 1970 were cancelled and the gallery was told to return to the estate any unsold paintings. The executors and gallery appealed the decision. The appeal court ruled on the case on November 22, 1977 affirming the decision made by the Surrogate Court in favour of Kate Rothko et al. (ML/MR)

1975: Willem de Kooning exhibitions in Japan and Paris.

1975: Willem de Kooning asks Mimi Kilgore to marry him.

Mimi said no, but continued her relationship with de Kooning.

Emilie ("Mimi") Kilgore:

"He was sitting in one of those chairs in front of the television set and I was sitting below him on the floor leaning on his chair, and I had turned around and was looking at him, and he asked me to marry him. I didn't know how to respond... It was tempting but it would have been too big a change. So many lives would have been affected." (DK560)

Spring 1975: Willem de Kooning completes twenty works in six months. (DK560)

October 1975: Willem de Kooning exhibition at Fourcade, Droll, Inc. (DK563)

1976

1976: Matta's son dies.

Roberto Matta's son, John Sebastian, fell from the window of his twin brother's studio, the artist Gordon Matta-Clark. He had been in and out of mental hospitals prior to his death.

1976: Robert Motherwell retrospectives in Dusseldorf and Stockholm. (HM)

1976: A major traveling exhibition of de Kooning's work is planned with sponsorship by the Hirshhorn Museum and the U.S. Information Agency.

The show would tour eleven cities in Europe and Eastern Europe, including Poland, Yugoslavia, Hungary and East Berlin. (DK564)

1976: Xavier Fourcade becomes Willem de Kooning's exclusive dealer. (DK491)

1976: Willem de Kooning visits the Rothko Chapel. (DK558)

From de Kooning: An American Master by Mark Stevens and Annalyn Swan:

"In 1976, de Kooning's half brother Koos paid a visit to the United States; de Kooning, at a loss how to entertain his relative, flew with him to Houston to see Mimi. At one point when she was busy teaching, Mimi asked the young painter John Alexander to take de Kooning to the Rothko Chapel so that he could see the somber abstractions Rothko painted shortly before his suicide. De Kooning sat on a bench in the chapel, perhaps remembering when he first met Rothko on the bench near Washington Square, and wept." (DK558)

October 1976: Fourcade mounts show of twelve new works by Willem de Kooning. (DK565)

Reviews were generally favourable. John Russell wrote in The New York Times, "Mr de Kooning in his 70s is still inventing new ways of mixing paint, new ways of getting it to do his will, new ways to accommodate the thrusts of the psyche." (DK565)

1977

1977: Robert Motherwell retrospective exhibitions in Vienna, Edinburgh and Paris. (HM)

1977: Robert Motherwell works on mural for the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.

The mural was commissioned by the National Gallery for I.M. Pei's annex which opened on June 1, 1978.

Summer 1977: Elaine de Kooning helps Willem de Kooning go to Alcoholic Anonymous. (DK567)

Elaine de Kooning had purchased a summer house near her husband in the Springs in 1969. In 1976 she became the Lamar Dodd Visiting Professor of Art at the University of Georgia and commuted between Georgia, New York and Long Island. In order to stop drinking she began attending AA meetings and while at one meeting in Bridgehampton she met a Montauk resident, Eugene Tritter, and asked if he would take Bill to some meetings. At the time Tritter had no idea who Bill was, but would eventually become the artist's "sponsor" in AA. (DK568/593)

Eugene Tritter:

"I genuinely enjoyed him [de Kooning] even after I knew he was famous. He was so funny. He'd say things like, 'You know, I'm really a pretty famous guy.' But it wouldn't make you mad. If you got to know him, it wasn't ego... Sometimes he'd come in his overalls [to AA meetings] that were all full of paint. He enjoyed that, because he had been a housepainter. He'd go to meetings and sit through them. I don't remember him talking a lot at AA." (DK568)

In addition to alcohol, Bill was also taking sedatives such as valium. At the time it was not uncommon for doctors to prescribe valium to help alcoholics withdraw from alcohol, not realizing that valium was even more physically addictive than alcohol. According to Tritter, "Pills keep up the sedative effect. And then you crash when you're back home and you drink again because you feel terrible." (DK569)

1978

1978: Robert Motherwell retrospective at the Royal Academy of Arts, London. (HM)

1978: "Mark Rothko, 1903-1970: A Retrospective" at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York.

Elaine de Kooning:

When I saw the retrospective at the Guggenheim, his paintings, as far as I'm concerned, shrank tremendously from when I saw them fresh. I mean the colors had dimmed. Well, that happens just physically with turpentine washes. The turpentine is not a substantial enough vehicle to maintain the color. Also, they didn't have the impact that they did at that time. But those big black paintings, they took me by surprise, because I had had them described and I doubted it. I mean, I didn't think that I would be as impressed as my informant was. But I was. I was tremendously impressed. I found them very grand and the scale of them, the size, it was just quite amazing... I felt that they had this sense of content and awareness of death. He didn't specify whether it was death, but this is the kind of thing in back of what he was talking about... Rothko's paintings to me were without surface. They are atmospheric. You can feel the colors hover, but you don't feel the paint describes a surface, the way the paint on a Clyfford Still canvas does. I mean, in Clyfford Still you see the actual surface. But with Rothko, there is no surface. There were no brush strokes and that color is definitely very atmospheric. (SE)

February 10 - April 23, 1978: "Willem de Kooning in East Hampton" exhibition at the Guggenheim Museum in New York. (DK565)

Organized by Diane Waldman with the help of Linda Shearer, it included 84 paintings, 24 drawings and 17 sculptures, all from the period 1962 - 1977. (NR) About half of the paintings (such as Whose Name Was Writ in Water) were from a series that de Kooning began in 1975. (DK580) With the exception of two paintings from 1962 all of the work was produced by de Kooning after moving to East Hampton in 1963. (NK)

Hilton Kramer reviewed the show for The New York Times:

Hilton Kramer:

"The East Hampton 'landscapes' are indeed the most orthodox examples of Abstract Expressionist painting that Mr. de Kooning has ever produced... Whether he is evoking the figure or his memories of a landscape, or the memories of other paintings (which one suspects is often the case), there is a visual quality in his work that is arresting and seductive. We are never in doubt that we are in the presence of a superior artist.

Why then do I find so much of this large exhibition so dispiriting?... It is not that the paintings lack structure, but that the structure is often so slack and loose, so utterly feckless in the face of the demands of the painterly energy it is called upon to support, that it seems almost to amount to a failure of will." (NK)

John Russell interviewed de Kooning in East Hampton for The New York Times prior to the exhibition, noting that "De Kooning sees very few people nowadays, and he doesn't much care to be interviewed or photographed. He spends virtually every day in the studio and virtually every evening at home, by himself... Insofar as he is formal at all, in his capacity of host, it is in relation to two monumental rocking chairs that he salvaged from a resort hotel... Now that de Kooning rarely leaves East Hampton and turns down even the most tempting of foreign invitations, these giant rockers seem to precipitate a free-running conversation in which memory and speculation, out-of-the way knowledge and shrewd comment, all play a part. " (NR)

John Russell [in The New York Times]:

"[De Kooning's] studio is large, as one might expect, but in architectural terms it is more like an engineering workshop than a place in which paintings and sculptures are made. Metal structures whizz this way and that across the ceiling. Thousand-watt Klieg lamps would have proved strong enough for the lobby of Grauman's Chinese Theater in the heydey of Hollywood. An enigmatic platform is cantilevered high into the air... Even the studio floor bears his personal mark, in that beneath every painting in progress sheets of newspaper are laid out to catch the paint that drips down (or is wiped off) as work goes forward... His studio tables look like a cross-mating of the workshop of a Renaissance chemist wit the kitchen of a very good cook who is big on sauces... To make precisely the right sexy juices for those new paintings demands an enormous application. Oil paint is thinned with water. Safflower oil, kerosene and mayonnaise are pressed into service as binding agents. 'One day,' he said, 'I'd like to get all the colors in the world into one single painting.'

...De Kooning uses (apart from knives and spatulas) everyday housepainters' brushes that come in a 'Pak-o-Four' for $1.49. He also has devices of his own invention - pullings and tuggings and overlays - for the perfecting of the licked look that gives so sumptuous a consistency to his recent paintings." (NR)

De Kooning explained the "enigmatic platform" by saying "It's just that when I make lithographs I like to look down at them from a height and see how they are getting on." In regard to the newspaper on the floor, he said, "You remember how it was with Matisse. Matisse at one time used to cover the studio floor with sheets of newspaper. Everyone thought he was anxious to protect the floor, but Matisse said no, he didn't care at all about the floor, but he did like the way the light was reflected off the sheets of newspaper... I'd like someday to do a studio. A studio like Matisse used to do, with two or three figures in an interior and maybe a table... Anyway, a big interior with figures." (NR)

May 1978: Elaine de Kooning gives up the right to control de Kooning's estate and resigns from the University of Georgia. (DK581)

Elaine wanted to resign from her teaching position at the University of Georgia, but was dependent on the salary. She discussed her options with Bill. Although they had lived separately for a long time, they were still legally married. De Kooning's lawyer, Lee Eastman drew up papers granting her a substantial financial settlement in exchange for her giving up the right to control de Kooning's estate. She agreed to the terms and quit her teaching job. (DK582)

May 1978: "American Art at Mid-Century: The Subjects of the Artist" opens the new East Building at the National Gallery in Washington. (DK581)

The exhibition in the new East Building (designed by I.M. Pei) included Willem de Kooning, Arshile Gorky, Jackson Pollock, Barnett Newman, Mark Rothko, Robert Motherwell and David Smith. (DK581)

Willem and Elaine de Kooning attended the black tie opening dinner on May 30th, hosted by Paul and Rachel "Bunny" Mellon for two hundred guests. (DK581)

July 11, 1978: Harold Rosenberg dies. (DK582)

Time magazine announced his death in the July 24, 1978 issue:

"DIED. Harold Rosenberg, 72, author (Saul Steinberg, Barnett Newman) and art critic of The New Yorker; of a stroke, in Springs, N.Y. Rosenberg's essays on Pollock, de Kooning, Gorky, Motherwell and Rothko, whom he called action painters, helped legitimise the first New York school of Abstract Expressionism in the '50s."

July 13, 1978: Thomas Hess dies. (DK582)

An announcement of Hess' death appeared in the same issue of Time magazine as that of Harold Rosenberg:

"DIED. Thomas B. Hess, 57, former editor of Art News magazine, who last February became chairman of 20th century art at the Metropolitan Museum; of a heart attack; in Manhattan. As art critic for New York magazine in the 1970s, Hess kept alive his romance with Abstract Expressionism."

July 1978: Willem de Kooning goes on a binge.

Saddened by the deaths of his friends, Harold Rosenberg and Thomas Hess (see above), de Kooning went on a binge. Joan Ward contacted Bill's AA sponsor, Eugene Tritter, who collected Bill from the Springs and took him to Montauk. Although their first evening together went well, when Bill woke the next morning he wanted to be taken home so he could have a drink, offering Tritter a painting if he complied. (DK583)

Elaine continued to try to keep de Kooning away from alcohol and de Kooning continued to drink, sometimes getting alcohol from Dane Dixon who, as a friend and employee found it difficult to say no. (DK583) She turned to her brother Conrad for help. Conrad and Elaine had become estranged because of her drinking but reconciled when Elaine stopped drinking. Conrad moved into the studio with Bill and with his sister went through the town asking local bars and liquor stores not to serve Bill. Elaine also tried giving Bill antabuse which causes a person to become ill should they have a drink. She added it to his eggs or health food drinks but he would still drink, ending up sick or unconscious. Once, when the writer Arnold Weinstein stopped by de Kooning's studio to take him to a party, he found de Kooning lying on the floor in what looked like a coma. He later recalled, "This was really terrible. My wife got really scared; she thought he was dead. We called up and got him to the hospital. He was drunk, and this was the response to the antabuse." (DK584)

August 27, 1978: Matta's son dies of pancreatic cancer at the age of 38.

Two years after his twin brother's death, Gordon Matta-Clark died of pancreatic cancer.

October 1978: Abstract Expressionism retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art. (DK581)

The first ever retrospective of Abstract Expressionism featured 120 paintings by 15 artists. (DK581)

1979

1979: Robert Motherwell retrospective exhibition at the William Benton Museum of Art, University of Connecticut. (HM)

March 1979: Philip Guston suffers a major heart attack.

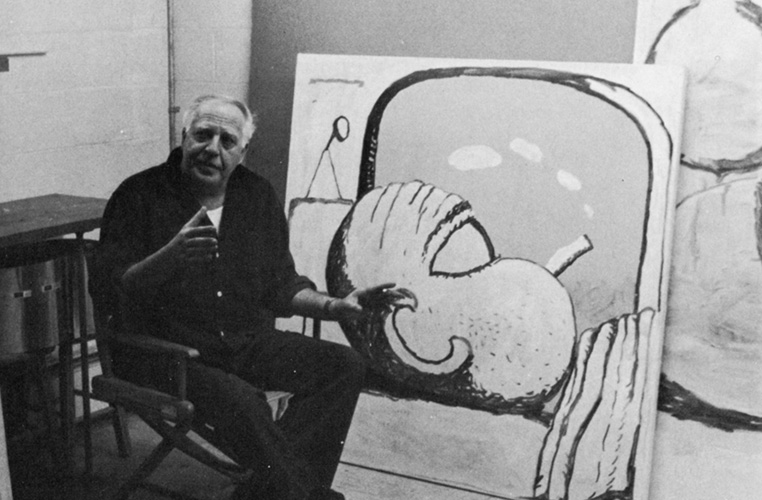

Philip Guston with Smoking I, 1973 (Photo: Barbara Sproul)

Guston had been talking on the phone to Mercedes Matter from his home in Woodstock. Stricken with pain he ended the conversation abruptly, went into the kitchen and vomited into the sink before collapsing unconscious on the floor. He ended up in the Coronary Care Unit at Benedictine Hospital in Kingston, New York.

Musa Mayer [Philip Guston's daughter]:

The beds in the Coronary Care Unit of Benedictine Hospital were arranged like spokes in a wheel around a central nursing station... My father's bed was cranked up as high as it would go... I approached the bed. His wrists were tied with strips of cloth to the two side rails. Angry tears sprang into my eyes. They had put my father in restraints!.. He began mumbling something about Nazis and interrogations. As he tried to speak, his tongue lolled in his mouth as if it didn't belong there - this from the Thorazine they'd given him when he'd begun to hallucinate the day before. (MM188)

Guston, suffering from delirium tremens, had imagined the hospital staff to be Nazis interrogating him. He fought back and had to be restrained. The extent of Guston's drink problem had previously gone unnoticed by his family.

Musa Mayer:

I knew he drank to calm his nerves and relieve pain; his preferred treatment, when his ulcer bothered him, was a glass of vodka and milk. Come to think of it, while we sat and talked, my father was usually drinking something from a jelly glass. And there were refills, too, repeated trips to the pantry, where the liquor was kept. I tried to think back, to remember. I had never even seen him drunk. Or had I? The truth was, I had never seen him acting drunk... In the studio that evening, I looked at his paintings. It wasn't as if he had hidden anything; the signs were clearly there. I simply hadn't wanted to see. In The Desire, painted only the year before a fist lies on a high red wall, clenched, as if to avoid clasping the highball glass beside it. And Head and Bottle, from 1975, has his lima bean-shaped head with its enormous, all-seeing eye glaring down fixedly at an empty green bottle. When I opened the kitchen cabinet my parents used for their medications, there were bottles and bottles of pills meant to help with anxiety and insomnia - Librium, Valium, Seconal, Dalmane... Illness and death had been much on my father's mind since my mother's stroke in 1977. (MM190-91)

His daughter was informed by the doctors that Guston might not recover from his heart attack. She informed her father.

Musa Mayer:

He listened with his eyes closed, then looked up at me and began to weep, silently, tears welling up and sliding down his cheeks into his ears.

"I want Kaddish said for me,'" he whispered. "It's very important... There are three men I want to say Kaddish for me. Do you understand?" I nodded. The three men were Morton Feldman, Philip Roth, and Ross Feld - the three dearest and deepest friends of his life. "But my poor dear Musa," he murmured. "What will happen to her?" Thinking of my mother brought fresh tears. I tried to reassure him that I would take care of her best as I could." (MM192)

Guston did eventually recover from that heart attack. A nurse recalled visiting his bedside when he was feeling better and asking him "Is there anything I can get for you Mr. Guston?" He replied "A nice stiff whiskey and a cigarette would be fine." (MM193)

Musa Mayer:

Cigarettes were part of him; they appear everywhere in his work. Almost every photograph of my father I've ever seen shows him smoking. In a painting that hangs in my study now, entitled Language II, among the familiar symbols of the shoe, the wheel, the manhole cover, the green glass shade, is the image of a cup of coffee with a butt in a little cloud about it, that represents, as my father told me, "a cup of coffee dreaming of a cigarette." (MM197)

Guston would die the following year - on June 7, 1980 from another heart attack after returning home from a retrospective of his work at the San Francisco Museum of Art.

c. April 1979: The damage to Mark Rothko's Harvard murals is reported.

A conservator's report revealed that between February 1978 and April 1979 the paintings had suffered numerous scratches and abrasions including a two-inch tear, a three inch dent, and someone named ALAN C had scratched his name onto Panel Three. By 1979, the room had become the "Party Function Room" and was rented out during the week for banquets, seminars and, on one occasion, an end-of-term disco party. (RO456) The room eventually became an office for the Harvard Real Estate Corporation and the murals, irreparably damaged, were moved permanently into Dark Storage at the Fogg Museum. (RO454)

1979: Willem de Kooning stops painting. (DK585)

The previous year de Kooning had given the impression to a journalist that painting was not a problem even though he was in his seventies.

Willem de Kooning [1978]:

"You get old, you get used to yourself. A painter can go down, way down, when he's waiting to go down. Franz Kline went very down, and I used to be so nervous I got palpitations. Now I don't have that trouble. I see the canvas, and I begin. But you have to keep on the very edge of something, all the time, or the picture dies." (NR)

As de Kooning continued to drink, Elaine took control of his studio, monitored his finances through his bookkeeper and oversaw who was fired or hired and who was allowed to visit him at the studio. Joan Ward thought that de Kooning stopped painting in an effort to resist Elaine. Ward would later say, "Think about it: I've captured the lion, and now the lion is no longer doing what makes him the lion. I've saved him from himself and he isn't painting? How's it going to look to the outside world?" (DK588)

Joan Ward:

"Bill was playing the game out to the end. He thought between the three of us [Joan, Elaine and Mimi] there would be a real push and pull... Come in and fight over me and let the best man win... But he didn't realize that as he was getting older and a little shaky, Elaine as the wife could come back and legally take over. And, I must admit, I retreated. It wasn't until he realized that he was trapped - that nobody was going to do battle - that he tried to rebel. But it was too late. He was trapped in his own trap." (DK588)

1979: Willem de Kooning writes his last letter to Mimi.

From De Kooning: An American Master by Mark Stevens and Annalyn Swan:

The year 1979 was extraordinarily difficult for de Kooning, not only because he was drinking but because he was deeply depressed. Sometimes, he hardly seemed to move, rendered helpless by a melancholy darkness closing over him... When the depression grew so severe that he could not bear it, he would demand a slug of whiskey. Occasionally, a combination of alcohol and sedatives left him disoriented and foggy... De Kooning's failing memory further deepened his depression and signaled a more general deterioration of his mental faculties. He was aware of the problem, painfully so, but spoke to no one about it. As early as 1974, before leaving for Georgia, de Kooning's longtime assistant John McMahon began noticing how vague de Kooning could be... In 1979, de Kooning wrote his last letter to Mimi. He could begin but not end it. He repeated the opening passage again and again. It was, said Mimi, "the same letter seven times"... (DK586)