Abstract Expressionism 1900 - 1909

by Gary Comenas

1900

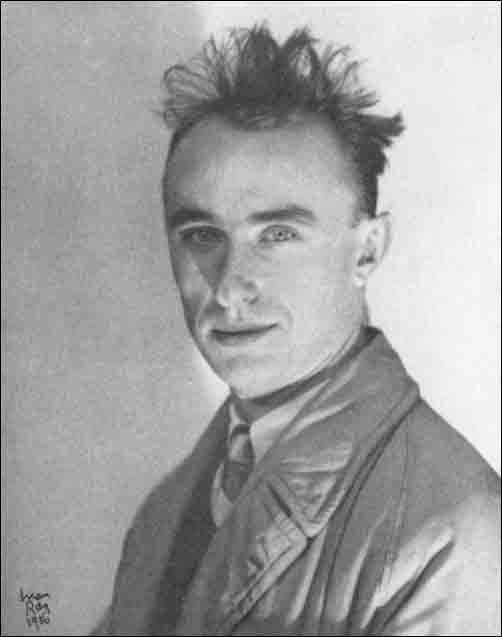

January 5, 1900: Yves Tanguy is born in Paris.

Surrealist Yves Tanguy, who would later be one of Arshile Gorky's neighbours in Connecticut, was born Raymond Georges Yves Tanguy in Paris to parents of Breton origin.

Yves Tanguy by Man Ray (1936)

From Arshile Gorky: His Life and Work by Hayden Herrera:

Of the friendship with Yves Tanguy and his wife, Kay Sage, Mougouch [Arshile Gorky's wife] recalls that 'Tanguy was very charming and he would sing in my ear, but Gorky was never jealous of Yves.' Sage, she said, was wonderful with Gorky, and Gorky felt protective of her because Tanguy was so rude to her, ignoring her and telling her to shut up. The well-brought-up Sage wanted everything to be perfectly arranged in her immaculately clean Colonial house... Wanting to arrange her husband as well, she tried to transform Tanguy into a country squire by equipping him with a shotgun and rifle as well as a hunting cap and a shooting jacket from Abercrombie and Fitch. Tanguy resisted. Instead, with his robust humour amplified by alcohol, he told tales of his vagabond youth. (HH496-7)

January 31, 1900: Betty Parsons is born.

Betty Parsons was born Betty Pierson in 1900 at 17 West 49th Street (now the site of Rockefeller Plaza) and was educated at the Chaps School and Miss Randall Keever's Finishing School. After seeing the Armory Show in 1913, she became interested in art and later studied sculpture with Gutzon Borglum (creator of Mount Rushmore). Her wealthy, conservative family disapproved of her following a career in art and was also opposed to women going to college.

When Parsons was nineteen years old she married Schuyler Livingston. She left him three years later and went to Paris for a divorce. She stayed for 11 years, studying art (sculpture) and hob nobbing with the likes of Alexander Calder, Man Ray, Hart Crane, Max Jacob, Gertrude Stein, and Dada founder Tristan Tzara.

In 1933 she returned to the United States (after the Depression wiped out her wealth) and first lived in Hollywood (where she met both Marlene Dietrich and Greta Garbo) before continuing on to Santa Barbara where she studied sculpture, gave art lessons, painted portraits and worked in a liquor store. After six years she returned to New York - a trip she financed by selling her engagement ring.

After she exhibited some of her work at the Midtown Gallery in New York, she was offered a job as a salesperson. (The owner of the gallery was Mary Sullivan who, with Abby Rockefeller and Lizzie Bliss, founded The Museum of Modern Art.) In early 1940 Parsons started a gallery in the basement of the Wakefield Bookshop on East 55th Street showing Joseph Cornell, Saul Steinberg, Hedda Sterne, Theodoros Stamos and Adolph Gottlieb. In 1944 she was hired by Mortimer Brandt to open a modern section in his gallery of Old Masters. She showed Rothko's watercolours there in the spring of 1946.

Brandt decided at the end of the 1946 season that modern art didn't sell and moved to a new location leaving his space at 15 East 57th Street which Parsons took over raising $5,000 - $1,000 of her own and $1,000 from each of four friends. (RO249-50) When Peggy Guggenheim moved back to Europe at the end of the 1947 spring season, Parsons took over her gallery space. Artists who would sign to Parsons gallery included Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, Clyfford Still, Barnett Newman, Ad Reinhardt and Theodoros Stamos.

Betty Parsons:

Most artists don't think I'm tough enough. That I don't go out and solicit, call up people all the time. I don't. I know how people hate that sort of thing, because I hate it myself, so I don't do it. (RO253)

August 15, 1900: Jack Tworkov is born in Biala, Poland.

Tworkov was the brother of artist Janice Biala. They immigrated to the United States as children in 1913. Tworkov was part of the WPA Federal Art Project from 1935 to 1941. From 1948 to 1953 he and Willem de Kooning had adjoining studios in New York.

1901

1901: Valentine Dudensing is born.

Dudensing founded the Dudensing Galleries in 1924 at 45 W. 44th Street in Manhattan. In c. 1926 the galleries were renamed F. Valentine Dudensing and later the Valentine Gallery. The gallery closed in 1948. Artists represented by the gallery included Henri Matisse, Mondrian and Milton Avery. Adolph Gottlieb had his first solo show at Dudensing's gallery in 1930. (GC/TH12)

1903

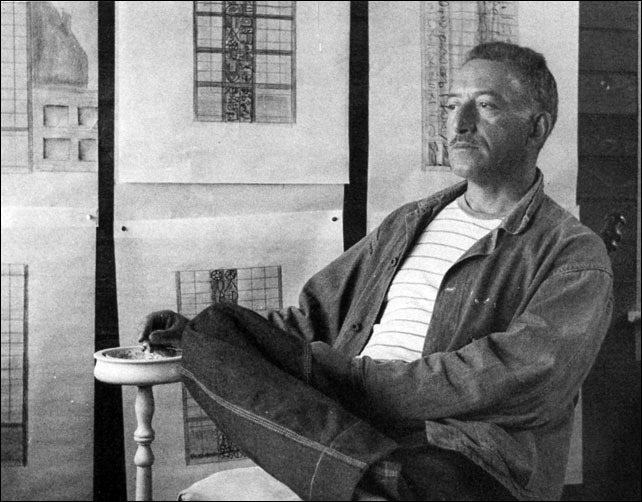

March 14, 1903: Adolph Gottlieb is born in New York.

Adolph Gottlieb in his Provincetown studio, 1952

(Photographer:

Maurice Berezov)

Gottlieb was born in downtown Manhattan.

Adolph Gottlieb:

I'm a born New Yorker. I don't know if it means anything to you, but I was born on Tenth Street, right across from Tompkins Square Park. I guess that makes me the original Tenth Street artist. But I left Tenth Street when I was about five or six years old. (JG254)

After leaving 10th Street, Gottlieb was raised by his family in the Bronx before moving with his family in the mid-1920s to 285 Riverside Drive in Manhattan. His father, Emil (1872-1947) had immigrated to the United States as a child with his family from what would later become known as Czechoslovakia. Emil's father established a stationary supply firm, L. Gottlieb & Sons and Adolph's father succeeded him in the family business. Gottlieb's mother, Elsie (née Berger, 1882-1958), was also a Jewish immigrant from Czechoslovakia. Her father was a wholesale grocer. Two sisters were born after Adolph's birth - Edna (1908-1956) and Rhoda (b. 1914). (AG11)

Unlike many of the Abstract Expressionists, Gottlieb had a financially comfortable childhood. According to him, his middle-class parents "deplored" his "being absorbed in art." As a child he would copy Mutt and Jeff comics, later saying he was "brought up with comic strips and the Gibson books on the library table." (AS)

Adolph Gottlieb [1967]:

Well, I was a very early, youthful rebel. I found that I was good at art when I was in high school and took as much art work as I could. It was what interested me. I wasn't interested primarily in making money. This didn't seem to me a reasonable goal. I rather despised people who were primarily interested in making money. So I decided I would be able to get along some way or other and do what I wanted to do. And I did that. Finally, it has worked out that I still don't think about money and I am able to sell and make a living with my work. (AS)

September 25, 1903: Mark Rothko is born in Dvinsk - at that time part of the Russian Empire, now Daugavpils, Latvia.

The Rothkowitz children

L-R: Albert, Sonia, unidentified man with moustache, Marcus (Mark) and Morris

Photographer unknown c. pre-1910

(portlandart.net)

Mark Rothko (born Marcus Rothkowitz) was the youngest of four children. His oldest brother was Moise, than a sister, Sonia and then another brother, Albert.

Rothko's early childhood was spent at 17 Shosseynaya in Dvinsk - then part of the Settlement of Pale which was home to most of Russia's five million Jews. Approximately half of Dvinsk's population of 11,000 was Jewish. Rothko's brother Moise later recalled that "We escaped pogroms," but that they did "have Cossacks; they would come in with whips and do what they wanted and scare the life out of people." According to artist/sculptor Herbert Ferber, Rothko once told him about "being carried in the arms of his mother or a nurse at one time when a Cossack rode by and slashed at them with a whip. And he had a scar on his nose which he claimed had been caused by the whip of a Cossack." (RO13) Another friend of Rothko, Al Jensen, recalled Rothko telling him about "a childhood memory of his family and relatives talking about a Czarist pogrom. The Cossacks took the Jews from the village to the woods and made them dig a large grave. Rothko said he pictured that square grave in the woods so vividly that he wasn't sure the massacre hadn't happened in his lifetime. He said he'd always been haunted by the image of that grave, and that in some profound way it was locked into his painting." (RO326) Historian Louis Greenberg referred to the period of 1906 - 1911 as "the worst in the history of Russian Jewry." (RO13)

Rothko would later change his name from Marcus Rothkowitz. According to Avis Berman, Rothko changed his name at the suggestion of art dealer J.B. Neumann who came up with "Rothko." (JK)

1904

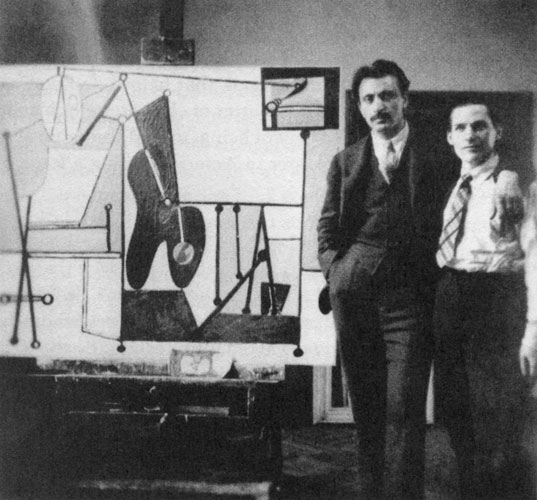

April 24, 1904: Willem de Kooning is born in Rotterdam.

Arshile Gorky (L) with Willem de Kooning in Gorky's studio, 36 Union Square, c. 1935

(Photographer unknown)

(DK)

Willem De Kooning was born at home at Zaagmolenstraat 13 in a working-class district of North Rotterdam to Leendert de Kooning (b. February 10, 1876) and his wife Cornelia (neé Nobel - March 3, 1877). Willem had one older sister Marie (b. 1899). His mother gave birth to several children between the time of Marie's birth and that of Willem but none of the children survived - twin girls who died several days after being born in 1901 and a daughter who died in 1902 at the age of 8 months. De Kooning felt loved by neither of his parents and was particularly fearful of his mother who could become violent. Photographer Dan Budnik later recalled that when Willem visited his mother in a nursing home in Rotterdam in 1968, de Kooning commented about the frail woman he saw, "That's the person I feared most in the whole world." (DK514) De Kooning's sister Marie became a sort of surrogate mother. It was to Marie whom de Kooning turned to when in trouble. As an adult de Kooning would write to his sister that he would "never forget," that while he was growing up, "you were always there to protect me." (DK13)

See Willem de Kooning's childhood.

September 23, 1904: Meyer Schapiro is born in Lithuania.

Art writer and educator, Meyer Schapiro, immigrated to the United States at the age of three. (MX) His father had immigrated the previous year and after finding work as a Hebrew teacher arranged for his family to follow. In 1940 a dissident group led by Schapiro withdrew from the Artists' Congress because of their failure to condemn the invasion of Finland by Russia. Members of the dissident group, including Adolph Gottlieb and Mark Rothko, then went on to form the Federation of Modern Painters and Sculptors. In addition to writing about art in various publications including The Nation and Partisan Review, Schapiro was a professor at his alma mater Columbia University. He began teaching there in 1928.

Robert Motherwell [1974]:

It was in order to study with Meyer Schapiro that I came to New York, which was the single most decisive factor in my development. He introduced me to European artists in exile here from the war in the 1940s, and this was the second most important factor in my orientation. I have great admiration for him as a sage, though I disagree with him on some judgments. I admire him as an irreplaceable man and as an extraordinary representative of the unique greatness of New York City. (MX)

November 30, 1904: Clyfford Still is born in Grandin, North Dakota. (RO224)

During his early childhood Still and his family moved from North Dakota to Spokane Washington. In Spokane his father found work as an accountant and in 1910 moved to Alberta, Canada to homestead. Still grew up moving between the family home in Spokane and the farm in Alberta. "My arms have been bloody to the elbows shucking wheat" he would later say when speaking of his childhood - "when there were snowstorms, you either stood up and lived or laid down and died." (RO224)

1905

January 29, 1905: Barnett Newman is born in New York.

Barnett Newman was born on January 29, 1905 at home (480 Cherry Street) on the Lower East Side of Manhattan - the oldest of four surviving children. An older brother had died in infancy. Barnett's brother George was born after him followed by two sisters - Gertrude and Sarah. (MH/TH9) The name "Barnett" was his parents' Americanisation of "Baruch," meaning "The Blessed." During his first year in high school in 1919, Barnett translated Baruch into the Latin "Benedict" and used it as a middle name or just used the extra "B" as an initial so he was referred to as "B.B." Later he commented that he wanted to be called B.B. because he was "getting tired of being called Barney all the time." (TH8)

Barnett's parents were Abraham Newman (born c. 1874) and Anna Steinberg Newman (b. 1882) - Jewish immigrants from the town of Lomza in Russian Poland who had immigrated to New York in 1900. (TH9) Barnett grew up in relative comfort - at least from a financial point of view. By 1911 when the Newman family moved to Tremont in the Bronx, his father owned a successful male clothing manufacturing company. (TH9/MH) (Note: The Thomas Hess biography of Newman dates the move to the Bronx in 1911 although the Barnett Newman Foundation includes it in 1915 in their chronology of the artist.)

Newman's first school was P.S. 2 on Henry Street in lower Manhattan. (MH) According to his mother, he began to draw as soon as he learned to hold a pencil. In kindergarten he had what he later referred to as his "first art experience" when he watched his teacher, who was trying to show the pupils how to tell time, draw a clock on the blackboard adding a curve for perspective. As a youth Newman would also also model small animals out of warm tar scraped from the pavement. (TH9)

Adrian Searle [art critic and curator]:

Barnett Newman was not Jackson Pollock, the consummate action painter. Nor was he Rothko, the gloomy suicide. He did not perform for the camera ('I am not a dancer!' he once said), and he didn't paint in a barn. He took care to wear a suit for photographers; he even wore a monocle. Like Magritte, he affected the disguise of the bourgeois. He doesn't fit in with our received notions of how painters in New York in the 1950s looked and behaved...

His work mostly consists of undifferentiated fields of flat colour interrupted by sometimes narrow, sometimes broader verticals, which have come to be called zips rather than stripes... A whole lot of difficult thinking goes on in his large, grand, apparently pared-down canvases. They are filled with resonances and silences, passages of stillness and sudden, surprising yet somehow inevitable events. At his best, Newman produced paintings that balanced calculation and reserve with intuitive leaps; he is a painter to whom the dictum that the whole is greater than the sum of its parts can truly be applied. (Adrian Searle, "Read Between the Lines," The Guardian (London: September 17, 2002)

1905: Misha Reznikoff is born in Kabilia, Russia.

De Kooning biographers, Mark Stevens and Annalyn Swan, describe Reznikoff as "a perennial gadabout who knew everyone and kept abreast of the gossip." (DK254) Misha (sometimes spelled Mischa or Micha) arrived in the U.S. in 1921, studying at the Rhode Island School of Design and the Art Students League (where he befriended Stuart Davis). Reznikoff was an early friend of both Arshile Gorky and Willem de Kooning. He had first met de Kooning when de Kooning was working for a design firm, the Eastman Brothers, soon after de Kooning moved to Manhattan in 1927. (DK97) It was with Reznikoff's help that de Kooning landed a job teaching at Black Mountain College in 1948. Reznikoff had asked the sculptor Peter Grippe (who ran the Atelier 17 print studio after its founder, Stanley William Hayter, returned to France) if he could do anything for de Kooning who was "down and out" and Grippes suggested de Kooning to Josef Albers who was organizing the summer session of Black Mountain.

(DK254/NMAA)

Reznikoff was married to Genevieve Naylor, one of the first woman photojournalists hired by the Associated Press. In 1940 Naylor and Reznikoff were sent to Brazil by the U.S. State Department's Office on Inter-American Affairs (OIAA) to photograph the country and promote American goodwill. The photographs taken by Naylor were exhibited in a one-woman show - rare for the time - at The Museum of Modern Art in New York and toured throughout the U.S. in 1944.

In a review of a show by Reznikoff at Knoedler's, Clement Greenberg referred to Reznikoff as a "frail talent" but that his "decollages" ventured into "the more dangerous and exciting territory of the abstract."

Clement Greenberg [The Nation, February 21, 1948]:

Misha Reznikoff, an American painter whose work is to be seen at Knoedler's, seems also a frail talent. But in his 'decollages' - which are large water colours that get their texture and some of their color from the effect left by peeling off various layers of the cardboard on which they are painted and then applying the color - Reznikoff ventures into the more dangerous and exciting territory of the abstract. Again, Reznikoff's talent is indisputable, and it shows to good effect in his two most abstract pictures - Brown Figure, which is a work of perfection, and Dances. Both of these are almost monotone in color and have a strength that is belied elsewhere in this show... His other paintings, though they seem so various among themselves in conception and design, are almost uniformly spoiled - some of them, like Party in the Evening and the Picassoid Masks, are just barely spoiled - by a decorative and faintly academic slickness and syrupy grace which in may cases ruin works that appear initially to have been well felt out. It is probably, however, that Reznikoff has it in him to say much more than he does in this show, and I look forward to his next.

Reznikoff died in 1971 in New York.

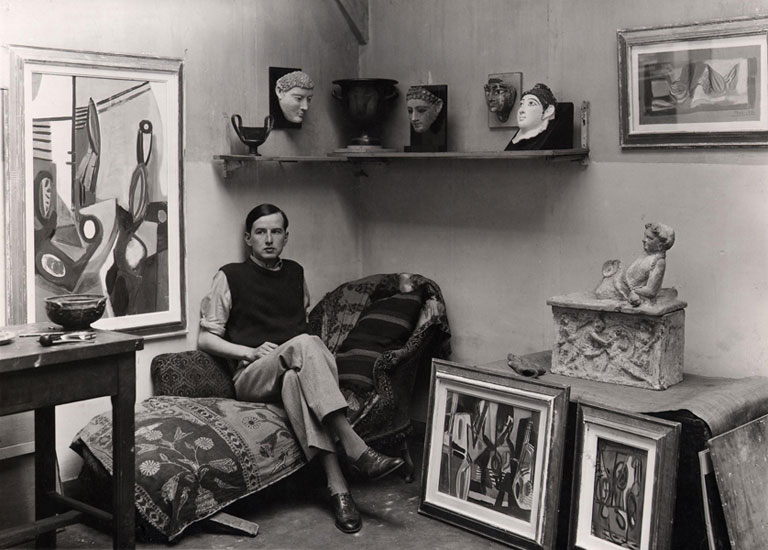

July 22, 1905: Wolfgang Robert Paalen is born in Baden, near Vienna Austria.

Wolfgang Paalen in his studio apartment in Paris, rue Permety, c. 1933

(Photo: Eva Sulzer)

Wolfgang Paalen's work was included in the 1936 exhibition, "Fantastic Art, Dada and Surrealism," at The Museum of Modern Art. He immigrated to the United States in 1939 and then moved to Mexico where he participated in the International Surrealist Exhibition at the Galeria de Arte Mexicano in Mexico City in 1940. The same year he traveled to New York for a solo exhibition at the Julien Levy Gallery and met Robert Motherwell, Adolph Gottlieb, Jackson Pollock and Barnett Newman. (CV)

In 1941 Motherwell studied with Paalen in Mexico for several months and Paalen encouraged Motherwell to collaborate with him on a new magazine he was planning named Dyn. He also introduced Motherwell to André Breton the same year. (CV). The first issue of Dyn was published in Mexico in 1942 and included Paalen's "Farewell au surréalisme." Only four issues of the magazine would be published from 1942 - 1944. During 1945, after the end of World War II, Paalen stayed with Motherwell during the summer and his book Form and Sense was published as the first book of Motherwell's Problems of Contemporary Art series.

In February 1948 Paalen traveled to New York and Chicago to plan a DYNATON exhibition in San Francisco and stayed with Motherwell during November and December in East Hampton to discuss the foundation of a new art school with Mark Rothko and Clyfford Still. By the time the school opened in October 1948 as The Subjects of Artist School, neither Still nor Paalen were still involved with it. (RO263)

On the night of September 24, 1959 Paalen committed suicide in Taxco, Mexico after a long depression made worse by alcohol and drugs.

October 17, 1905: John Ferren is born.

John Ferren was the only American artist included in the opening show of Peggy Guggenheim's Art of This Century Gallery in 1942. He was one of the few American artists who had actually been to Europe by the time of the exhibition. He had traveled there in 1929, studying at the Sorbonne in Paris and briefly at the Universita degli Studi in Florence and the Universidad de Salamanca. He returned to the United States in 1930 (where he had his first solo exhibition at the Art Center in San Francisco) and then went back to Paris in 1931 where he participated in workshops at Stanley Hayter’s Atelier 17 before returning to the United States in 1938.

Ferren was an active member of The Club when it first opened in New York. When Philip Pavia, who organized the events at The Club, relinquished his responsibilities in the spring of 1955, Ferren took over for about a year until Irving Sandler replaced him in 1956.

(IS32)

Late 1905: The 291 Gallery opens at 291 Fifth Avenue, New York.

The gallery was founded by Alfred Stieglitz and Edward (originally Eduard) Steichen. It was initially called the Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession but became known as the 291 Gallery because of its address. (FG99)

Although the Armory Show of 1913 is often credited as introducing European modern art to the United States, at least some of the artists included in the Armory Show exhibited at the 291 Gallery first. Henri Matisse had his first ever American exhibition there in April 1908 and the work of Cézanne was introduced to the American public there with a show of his watercolours in March 1911. During April 1911 the gallery presented the first solo show of Pablo Picasso with an exhibition featuring his watercolours and drawings. (AE) (According to John Richardson in the second volume of his Pablo Picasso biography, the Picasso exhibition at 291 was in March 1911. (PV310))

Samuel Kootz, who would open his own art gallery in New York in April 1945 was a regular visitor to Stieglitz' gallery during the 1920s.

Samuel Kootz:

I used to come for weekends to New York and visit two galleries that seemed to me to be promoting painting that was a little advance of what else was being shown in New York. That was the Stieglitz Gallery and the Charles Daniel Gallery. Stieglitz was showing Dove, Marin, Demuth, O'Keeffe, Hartley, Weber. And Daniel was showing Peter Blume, Dickinson, Kuniyoshi, and a number of other men who at that time were striving to be a little more personal, a little more ambitious in getting out of the Puritan strain of American painting... Stieglitz took a group of men and stayed with them. It seemed to me that in spite of what everybody has idealized that particular gallery for, that Stieglitz, actually, being an enormous personality himself, really did no good for the artist. Poor Hartley was trying to get $4.00 a week to live on at that period. Dove was being supported by an occasional purchase by Duncan Phillips. And this went on all through the group. I remember my antagonism when someone would come in to ask about buying a Marin watercolour, and Stieglitz would try to find out whether he was entitled to own a Marin watercolour, or whether he could spend enough to support Marin for one year in order to own that watercolour. This seems to me to be in violent opposition to a correct gallery attitude which is to keep the man alive and not interpose any objections to the purchase of a picture. (KD)

1906

February 2, 1906: Art writer Harold Rosenberg is born in New York.

Rosenberg coined the term "action painting" in his article "The American Action Painters" in the December 1952 issue of Art News. (JP210/274n210).

Harold Rosenberg [from "The American Action Painters"]:

At a certain moment the canvas began to appear to one American painter after another as an arena in which to act - rather than as a space in which to reproduce, redesign, analyse or 'express' an object, actual or imagined... Call this painting 'abstract' or 'Expressionist' or 'Abstract-Expressionist,' what counts is its special motive for extinguishing the object, which is not the same as in other abstract or Expressionist phases of modern art... Many of the painters were 'Marxists' (WPA unions, artists' congresses); they had been trying to paint Society. Others had been trying to paint Art (Cubism, Post-Impressionism) - it amounts to the same thing. The big moment came when it was decided to paint... just to PAINT. The gesture on the canvas was a gesture of liberation, from Value - political, aesthetic, moral... So far, the silence of American literature on the new painting amounts to a scandal. (AT589-92/DK353)

Although Jackson Pollock was not specifically mentioned in the article he assumed that Rosenberg was writing about him. Hans Namuth's photographs of Pollock energetically working on several paintings, including Autumn Rhythm: Number 30, 1950, had appeared in the May 1951 issue of Art News. Namuth's film on Pollock, which showed the artist painting on glass with the camera situated beneath the glass, had premiered at The Museum of Modern Art on June 14, 1951.

From Jackson Pollock: A Biography

by Deborah Solomon:

Pollock was appalled by Rosenberg's famous essay on 'action painting' ... Pollock felt sure that that the piece was about him. It had to be, for it even included a comment he had once made to Rosenberg. The previous summer, a time when he was having difficulty getting down to work, he had casually referred to his canvas as an 'arena'... The last thing he had meant to imply was that he considered the canvas 'an arena in which to act,' but there was his word, completely out of context, with Rosenberg building a theory around it and caricaturing him as a Promethean paint-flinger who cared more about the act of hurling paint than making good paintings... To the outside world he was suddenly an 'action painter,' a title that must have struck him as cruelly ironic. His creative powers had begun to wane. Inside his studio the action was virtually over. (JP237)

In June 1970 Rosenberg denied that his term "Action Painting" was synonymous with Abstract Expressionism although did not deny that it applied to Pollock, saying that "Action Painting was not intended to describe Rothko, Still, Gottlieb or Newman. Nor Gorky either... In short, A.P. [Action Painting] is not a synonym for Abstract Expressionism, though there is a connection..." (JE)

October 18, 1906: James Brooks is born.

James Brooks was born James David Brooks in St. Louis and studied art at the Southern Methodist University and the Dallas Art Institute. He arrived in New York in 1927, studied at the Art Students League while working as a commercial artist and joined the Mural Division of the Federal Art Project in 1936. He served as an art correspondent for the United States Army from 1942 to 1945.

He was photographed as one of the "Irascibles" by Life magazine in 1950, participated in the NInth Street Show in 1951 and was one of the artists representing the "American Vanguard" at the Sidney Janis Gallery in 1951 and the Galerie de France in Paris in 1952. As with Pollock and de Kooning he had a home in the Springs area of Long Island and served as a pallbearer at Pollock's funeral (wearing one of Pollock's suits that Krasner loaned him for the occasion). (JP250) He had been friends with Pollock and exhibited with Pollock and Krasner in the "Ten East Hampton Abstractionists" show which opened at the Guild Hall in East Hampton on July 1, 1950 (which also included the work of John Little, Wilfrid Zogbaum, Buffie Johnson and others. (JP207)

He died on March 9, 1992 after suffering from Alzheimer's disease since 1985.

From his obituary in The New York Times ["James Brooks, an Artist, Is Dead; Abstract Expressionist Was 85" (March 12, 1992)]:

James Brooks, one of the last of the original generation of Abstract Expressionist painters, died on Monday at Brookhaven Memorial Hospital in Brookhaven, L.I. He was 85 years old and lived in Springs, L.I. He had Alzheimer's disease since 1985, said his wife, Charlotte Park Brooks.

Known as a lyrical painter, Mr. Brooks was one of the most technically accomplished -- if not the most innovative -- members of the New York School. His skilled, rhythmic compositions of abstract shapes, textures and color values, carefully orchestrated in shallow space on the canvas, brought acclaim from critics as well as several major prizes. One was awarded by the Carnegie International exhibition in 1956 and another by the Art Institute of Chicago in 1957. A decade later, he was given a full-scale retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York City...

In his first one-man show at the Peridot Gallery in 1950, he presented stained and "dripped" canvases, influenced by his close friend Jackson Pollock, in which stains made on the reverse side of the canvas were used to generate "spontaneous" painted shapes on the front.

In 1951, he participated in the historic "Ninth Street Exhibition," an artist-organized show that included the work of Pollock, Hans Hofmann, Franz Kline, Willem de Kooning and Robert Motherwell. In 1956, his work was part of the "Twelve Americans" show at the Museum of Modern Art, as well as the Modern's influential "New American Painting" show in 1959, which traveled through Europe.

His wife is his only survivor.

1907

September 4, 1907: Leo Castelli is born.

Art dealer Leo Castelli was born Leo Krauss in Trieste. His first passion was not art, but literature.

Leo Castelli:

Literature was the first passion in my life, and it was, as I suppose it is for many of us, a way of finding out about myself. My father was a bank executive, and during World War I my family went to Vienna. By the time we moved back to Trieste three years later, I had learned to speak and read German... My father felt I should have a career in business, so after I finished law school he managed to have me placed in an insurance company... I tried it for a year, but finally told my father that I wanted to quit and study comparative literature and become a teacher... He made a bargain with me: if after working in a branch office of the insurance company in Rumania for a year I still wanted a career in literature, he would be happy to support my studies. So in the spring of 1932 I went to Bucharest, I was as bored as ever with the insurance business, but my social life had surprises in store. After a few months I met Ileana Schapira, the daughter of a Rumanian industrialist, and we married the following autumn. Ileana shared my love of literature, and we also seemed to bring out in each other an interest in collecting, mainly antiques at that time... My father-in-law was very wealthy, so we could afford practically anything: travel, a beautiful apartment, antiques, whatever. (AD81)

Ileana's father managed to get Leo a position with the Paris branch of the Banca d'Italia. Although he "did not like banking any more than Paris," he did enjoy the social life of Paris. One of the people he befriended was the architect/interior designer Rene Drouin and with the financial support of Ileana's father, Drouin and Castelli opened a gallery between the Hotel Ritz and Schiaparelli's. The gallery was meant to display paintings, contemporary furniture and objects d'art, much of it in the Art Deco style which Drouin planned to design himself. But due to the influence of another friend of Castelli, the Surrealist Leonor Fini, Drouin's Art Deco furniture, according to Castelli, "was overshadowed by the fantastic creations of our Surrealist friends." The first show at the gallery, which opened in the Spring of 1939, was of a single work: Pavel Tchelitchew's Phenomena. According to Castelli, "Le tout Paris showed up for the opening, and we really seemed to be on our way." (AD82)

Unfortunately, Hitler was also on his way. Drouin joined the French Army and Ileana and Leo retreated to the south of France. They escaped the German invasion of 1940 via a complicated route through Algeria, Morocco and Spain, finally arriving in New York in 1941. A year later they were living on the fourth floor of a town house at 4 East Seventy-seventh Street - a building owned and renovated by Ileana's father. From 1943 - 1946 Castelli served with the U.S. Army. After his stint in the Army he worked for the Paris Gallery as their U.S. representative. Among his clients were Baroness Hilla Rebay. During this time, he was also supposed to be working for his father-in law's subsidiary company, a sweater factory, but Castelli later admitted that his "heart and mind were elsewhere, either on East Tenth Street with the artists, or at The Museum of Modern Art." (AD84) In 1949 he ended his association with the Paris gallery - by which time he had got to know the art dealer Sidney Janis and many of the Abstract Expressionists. In 1950, he helped Janis organize the "Young Painters in the U.S. and France" and in 1951 played a key role in organizing the "Ninth Street Show." In February 1957, feeling that he "couldn't go on doing petty deals with Janis" he opened his own gallery in his apartment.

Leo Castelli:

My first show was a declaration of intention: I wanted to indicate that the American artists were just as important as the European artists, perhaps more so. I placed three of them - de Kooning, Pollock and David Smith - next to a number of recognized Europeans including Dubuffet, Léger, Picabia and Mondrian. The Mondrian came from Harry Holtzman, a friend of the artist who inherited everything Mondrian had when he died. Holtzman wanted $30,000 for it. Pollock was, at that time, selling for maybe $5,000 or $6,000. So $30,000, I told Holtzman was an outrageous price, and I'd never be able to sell it. He said never mind, it doesn't matter, but that's what the price is. To buy a Mondrian of that caliber today would cost over $1 million, maybe even $2 million, but of course I didn't sell it, and it went back to Holtzman. My hope was that later would include younger European and American artists. (AD87)

In May 1957, Castelli put on an exhibition titled "New Work" which included a Jasper Johns flag and a Rauschenberg "Combine" painting (Gloria). In January 1958 hosted a solo show of Johns' work. Eventually he took on many of the Pop artists including Roy Lichtenstein and Andy Warhol.

In 1959 Castelli and his wife divorced and she married Michael Sonnabend who she had first met in the 1940s when both were taking classes at Columbia University. As Ileana Sonnabend she opened a gallery with her new husband in Paris in 1962 with a show of Jasper Johns. She kept in touch with Castelli and showed many of the same artists. In the autumn of 1971 both she and Castelli opened galleries one floor apart at 420 West Broadway which, according to his The New York Times obituary, heralded "the arrival of the Soho gallery scene."

Castelli died on August 21, 1999 at his home in Manhattan.

1908

February 3, 1908: Exhibition of "The Eight" opens at the Macbeth Gallery, 450 Fifth Avenue, New York. (VA)

The full name of the exhibition was "Paintings by Eight American Artists Resident in New York and Boston." The participating artists became known as The Eight and would later also be referred to as Ashcan painters or painters of the Ashcan school (sometimes spelled with two words as in Ash Can).

In addition to the Macbeth Gallery, the exhibition was also shown in Chicago (at the Art Institute), Toledo, Detroit, Indianapolis, Cincinnati, Pittsburgh, Bridgeport and Newark and Philadelphia (Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts). (VA) The organizer of the show, Robert Henri (born Robert Henry Cozad on June 25, 1865 in Cincinnati, Ohio) had been a student at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts (beginning in 1886) and had previously exhibited there, including a solo show in 1897.

(FG69)

Four of the members of The Eight had previously been known as the "The Four" or the "Philadelphia Four." The group consisted of four illustrators from the Philadelphia Press newspaper who gathered regularly in Robert Henri's studio in Philadelphia to discuss art and culture. They were: William Glackens, George Luks, Everett Shinn and John Sloan. (RF) Those four artists later became part of The Eight. The other four members of The Eight were Robert Henri, Maurice Prendergast, Ernest Lawson and Arthur B. Davies.

Robert Henri had been spurred on to organize the exhibition of The Eight after a disagreement with the National Academy of Design where he had been elected an Associate Member in 1905 and an Academician in 1906. Henri was on the the jury for the Academy's annual exhibition in 1907 but walked out after accusing his fellow jurors of bias and unfair procedures. He withdrew two of his three entries from the exhibition and took his case to the press. (VA) The idea of staging an independent exhibition of The Eight was brought up at a dinner at John Sloan's house in March 2007.

From Landscape with Figures: A History of Art Dealing in the United States (2000) by Malcolm Goldstein:

The notion of staging a group show came up quite casually on March 13, 1907, when Henri and Luks went to dinner at the apartment of of Sloan and his wife... Prendergast was a late addition, having been invited by Davies to show along with the others after Macbeth's commitment was in hand. Moreover the artists were a mixed lot with respect to what they liked to paint and how they painted it; in their choice of subjects and their technique at least four of the Eight, Davies, Lawson, Prendergast, and Shinn, were closely akin to such American Impressionists among their older contemporaries as Frank W. Benson, Childe Hassam, and John Twachtman, men who late in 1897 along with seven other artists had formed a group that came to be known as the Ten American Painters. The others among the Eight were less romantic in their subjects; their depictions of city life eventually caused the entire Eight and other American realists to be known as the 'Ashcan school.' The term was invented by Art Young, a cartoonist for the Masses, the satirical (eventually socialist) magazine to which Davies, Sloan, and the Luks were contributors. (FG67-8)

The exhibition at the Macbeth gallery consisted of 63 works. The owner of the gallery, William Macbeth stipulated that he should receive 25% of the take and required a $400 guarantee. (FG67) Shortly before the opening each artist also contributed an additional $45 to cover expenses. (FG331n23)

The show was a success, both critically and financially. Seven paintings were sold for just under $4,000, a considerable amount of money at the time for work by American artists. (FG69)

1909

1909 - 1912: Stuart Davis studies art at Robert Henri's school.

Stuart Davis dropped out of high school in order to attend Henri's school the year that it opened. In 1910 Henri secretly sold the school to Homer Boss but continued to teach there until 1912. He began teaching at the Art Students League in 1915. (RA)

January 16, 1909: Clement Greenberg is born in the Bronx, New York.

Clement Greenberg was the reviewer for The Nation and Partisan Review. In 1955 he was hired by the gallery, French and Co., as an artistic advisor - something which Irving Sandler, who began writing for Art News in 1956, thought was "suspect" and "hurt his reputation." In 1961, however, after Greenberg's essays were published in book form, Sandler noted that Greenberg "quickly outstripped Harold [Rosenberg] in influence and prestige." (IS184-5)

Irving Sandler:

Clement Greenberg was not as highly regarded by my circle of friends in the 1950s as Harold [Rosenberg] and Thomas Hess. For example, in 1957, Philip Guston put Clem down as 'a mixture of unlearned art historian, semi-Marxist, and box-score keeper'...I never liked Clem, but I was always cordial to him and he to me...

Clem formulated three major premises. The fist was a theory of the historical development of modernist or avant-garde or mainstream art (the terms were used interchangeably). According to Clem, what made any art modernist was its quest for 'purity,' and it achieved this by separating itself from every other art. In the case of painting, it had to 'confine itself to the disposition pure and simple of color and line, and not intrigue us by associations with things we can experience more authentically elsewhere...'

Toward what had modernist art progressed? What was the 'mainstream,' as Clem saw it? In 1944, he announced, 'Abstract art today is the only stream that flows toward an ocean.' Anointed by history, it opened up to the future. Conversely, figurative art was banished to the dustbin of history. Consequently, Clem hailed Abstract Expressionism generally - and Pollock in particular - as the modernist painting (and in sculpture, David Smith)...

Clem's second theoretical premise was that the primary function of art criticism was judging quality... Aesthetic experience was immediate and involuntary; an instant glance was sufficient. The recognition of quality - the 'conviction' that a work had it - depended on individual taste or an 'eye' for art...

Clem's third supposition was that when avant-garde styles become academic, new styles emerge from their ruins.... This was Clem's most useful idea, one more fully developed by Michael Fried...

In the end I found it impossible to integrate logically Clem's historically deterministic theory of the progressive purification of the medium (which was very questionable in itself) and his idea that painting could advance through retrogressive moves, and his conception of the role of quality, which was purely subjective (although he later revised this tenet, claiming quality could be objective)... In any case, I was preoccupied with the meaning of art, and I could not accept his exclusively formalist analysis. In my view, if art has an human significance, it reaches beyond formal matters to an artist's vision and emotions... (IS184-7)

Not everyone shared Sandler's negative view of "Clem." In the March 1998 issue of Art Forum, art theorist Arthur Danto referred to Greenberg as one of "the century's great philosophers of art." (IS185)