Women in Revolt

by Gary Comenas

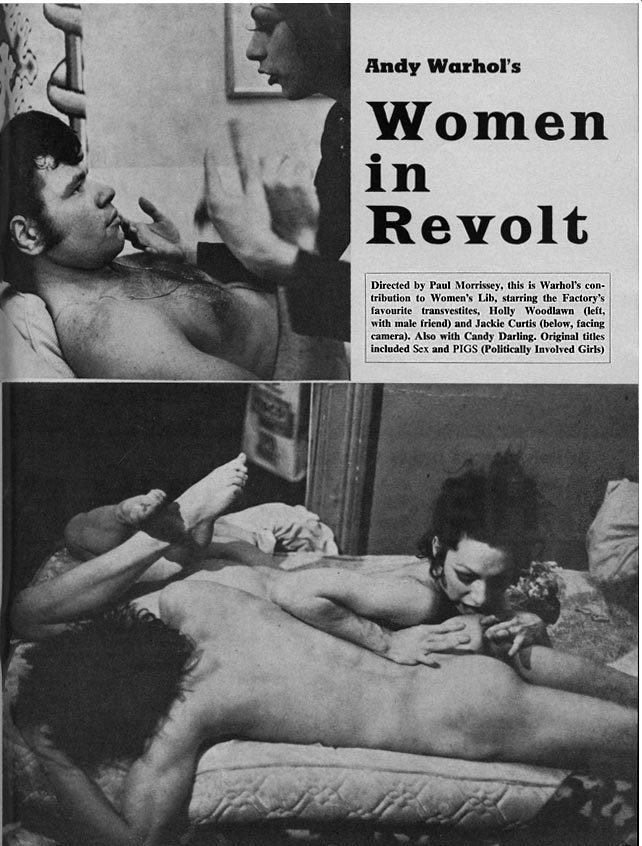

Full page spread on Women in Revolt in Films and Filming magazine (London), August 1973, p. 73 (Although both pictures feature Holly Woodlawn, the drag queen in the bottom photo is incorrectly credited as Jackie Curtis - one of Woodlawn's co-stars in the film. Note also that, although the film is advertised as "Andy Warhol's Women in Revolt," the director of the film is listed as Paul Morrissey in the boxed credits. The film is described as "Warhol's contribution to Women's Lib.")

97 mins. - Director: Paul Morrissey

Partial cast listing: Jackie Curtis (Jackie) - Candy Darling (Candy) - Holly Woodlawn (Holly) - Marty Kove (Marty) - Maurice Braddell (Candy's father) - Duncan MacKenzie (Duncan, Candy's brother), Jonathan Kramer (journalist), Johnny Kemper (Johnny Minute), Michael Sklar (Max Morris), Sean O'Meara (Mrs. Fitzpatrick), Jane Forth (Jane, Mrs Fitzpatrick's niece) - George Abagnalo (photographer) - Dusty Springs (Jackie's houseboy), Paul Kilb (Jackie's first boyfriend), Geri Miller, Brigid Polk (PIG women) (FPM136-7)

-----

1. Is Women in Revolt a Paul Morrissey film or an Andy Warhol film?

Women in Revolt was directed by Paul Morrissey.

In regard to the question of who produced the film, Warhol is not credited as the producer in the on-screen credits of the version released by First Independent, but IMDB currently (April 2022) lists him as the producer, along with Jed Johnson as the associate producer and Paul Morrissey as executive producer. He is also referred to as the producer of the film in the second volume of the film cat. rais.

Presumably, the film was paid for by Warhol under the aegis of Andy Warhol Films Inc. and, therefore, was produced by Warhol. The assignation of "producer" in regard to a film does not necessarily imply a creative role. For instance, Warhol is credited as the "producer" of another Morrissey film, Flesh, even though he was recovering from the gun wounds inflicted by Valerie Solanas when it was being made, and was never involved in the filming.

Warhol biographer, Blake Gopnik, argues that Flesh was a Warhol film because it was financed by Warhol Films Inc.:

Blake Gopnik:

However much Flesh wasn't by Warhol... it was most definitely 'an Andy Warhol film,' given that it was the first product to come out of the sleek new offices of Andy Warhol Films, inc. Its ads proclaimed Flesh to be presented by Andy Warhol in the way a classic Hollywood picture might be 'presented by' Warner Bros or Paramount. (Blake Gopnik, Warhol: Life as Art, Chapter 36)

Warhol's name was used in advertising because Warhol was better-known than Morrissey, but should fame determine the 'authorship' of a film? I wouldn't refer to a Godard film, say Breathless, as a 'de Beauregard film' (the name of the producer). Classic Hollywood pictures might have been referred to as a Warner Bros. or Paramount Film, but that was when actors and actresses were contracted to studios for what was usually a substantial period of time for a number of pictures. During the late '60s and '70s, it is doubtful that anyone would refer to Easy Rider, The Graduate, or Midnight Cowboy by the studios that produced the films - or even know who the studios were.

Later releases of the Morrissey films corrected the problem of authorship. On VHS and DVD versions of Flesh, the wording is: "Andy Warhol presents A film by PAUL MORRISSEY." The same is true of Women in Revolt: "Andy Warhol presents A film by PAUL MORRISSEY." So somewhere down the line, it was decided by the powers that be that Women in Revolt wasn't 'an Andy Warhol film,' It was (as advertised on the packaging), "A film by PAUL MORRISSEY." That's still the case today. Women in Revolt is a Morrissey film because it was Morrissey who directed it - Morrissey who was the 'auteur.'

According to the film scholar, J. Hoberman, the Warhol Foundation granted the rights to both Flesh and Women in Revolt to Morrissey.

J. Hoberman ("A Warhol Film Surfaces, but Is It His?," New York Times, January 18, 2013):

Around the time that Mr. Morrissey completed “San Diego Surf” he came to an agreement with the Warhol Foundation, securing the rights to “Flesh,” “Trash,” and other Warhol productions and waiving them for movies like “Lonesome Cowboys” and others, including “San Diego Surf,” on which he might have a legitimate claim. Thus the 1971 feature “Women in Revolt,” a more interesting movie than “San Diego Surf” (and, according to my research, one in which Warhol was far more involved), is credited to, and owned, by Mr. Morrissey, while “San Diego Surf” is attributed to Warhol and owned by the Warhol Museum.

Women in Revolt is written about as a Morrissey film in The Films of Paul Morrissey by Maurice Yacowar, although there are problems with the filmography in that book. Yacowar also attributes The Chelsea Girls to Morrissey as the sole director when the film is generally attributed to Andy Warhol.

Given that Paul Morrissey has always maintained that he directed the Women in Revolt and that, legally, he now owns the rights to the film, it means that three of Warhol's best known "superstars" - Candy Darling, Jackie Curtis and Holly Woodlawn - never actually appeared in a movie directed by Andy Warhol. Darling and Curtis also appeared in Flesh, but that film was directed by Paul Morrissey. Holly Woodlawn appeared in Trash, but that was also directed by Paul Morrissey. Even a bit player in Women in Revolt has referred to herself as a "Warhol superstar" in advertising for her cabaret show in New York (and captioned as such in a BBC documentary on Warhol), despite never having been in a film directed by Andy Warhol.

2. Did Andy Warhol film any of the scenes in Women in Revolt?

Footage in the David Bailey documentary on Andy Warhol is sometimes mistaken as a scene being shot for Women in Revolt. The scene, however, does not appear in the film (at least not in the First Independent release in the UK), and looks staged.

When Jackie Curtis and Holly Woodlawn were interviewed separately by Patrick Smith in 1978, both claimed that Warhol operated the camera during at least some of the scenes of the film.

Jackie Curtis (Patrick S. Smith, Andy Warhol's Art and Films (Ann Arbor: UMI Research Press, 1986), p. 272:

It would have been better if Paul Morrissey left his two fucking cents out... My big scene was when I was painting my toenails, and Paul Morrissey wanted that scene out, but I wanted it, and Andy said, 'I want the scene in.' That's it. I told Andy that I'd be in it only if he'd be behind the camera, and all the scenes that I'm in, Andy shot them. At least, I could say, 'I did the movie for Andy'...

In her interview with Smith, Holly says that Warhol turned the camera on during her scenes.

Holly Woodlawn: In Women in Revolt, I worked with Andy. He did the filming on that. I remember once he put the film in backwards. It was funny.

Patrick Smith: Now, Jackie told me that Jackie insisted that Andy be behind the camera when Jackie's scenes were being shot. Did Paul [Morrissey] stay behind the camera for the rest of the movie?

HW: No. Andy was...

PS: Andy was behind it?

HW: Paul was there, but Andy was the one who actually turned it on. (Ibid, p. 525)

Holly later contradicted herself in her autobiography. In A Low Life in High Heels, she writes (with the help of co-author Jeff Copeland), "... Jackie Curtis told the story about how, during the filming of Women in Revolt, she demanded that Andy shoot all of her scenes and, in doing so, Andy loaded the film backward. Miss Curtis was obviously out of her mind when she spun that yard. Andy never got behind the camera and she never made such a demand because Paul would not have allowed it." (HW13)

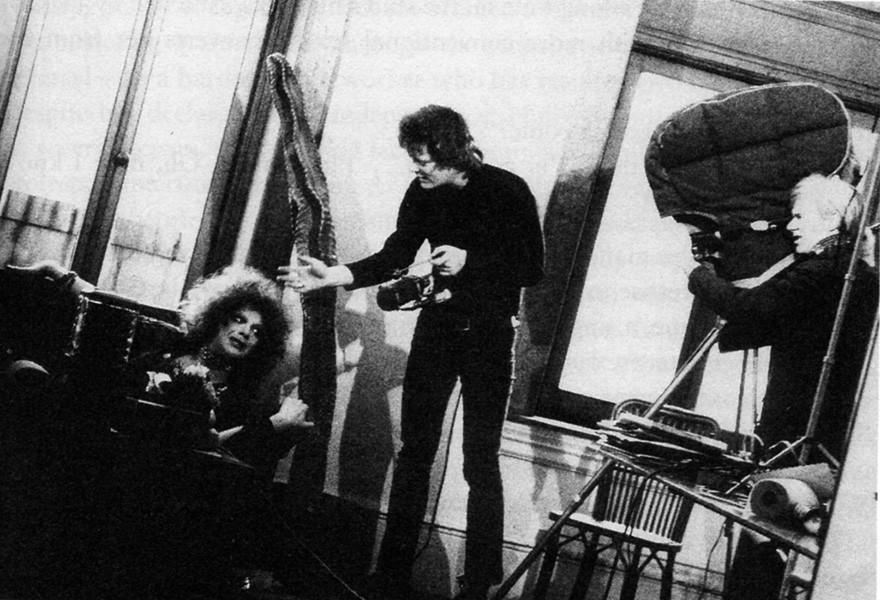

A photograph appears in Yacowar's book which apparently shows Andy Warhol behind the camera during one of Jackie Curtis' scenes.

The photograph is captioned, "Paul Morrissey directs Jackie Curtis in Women in Revolt while Andy Warhol operates the camera." (FPM57)

3. Women in Revolt, the Women's Liberation Movement and Valerie Solanas

Women in Revolt has been referred to as a satire on the Women's Liberation Movement and has also been linked to the attempted murder of Warhol in 1968 by Valerie Solanas. Bob Colacello claimed that "Although Paul [Morrissey] didn't come out and say it, and Andy certainly would have denied it, Women in Revolt is essentially Andy's revenge on Valerie Solanas." (Holy Terror, p. 78)

J.J. Murphy, Professor of Film at the University of Wisconsin, writes "The specter of Valerie Solanas hangs over Women in Revolt (1971), Morrissey's satire of the women's movement." (The Black Hole of the Camera: The films of Andy Warhol (London: University of California Press, 2012), p. 239). (For more on Valerie Solanas, see "Valerie Solanas.")

Questions were being asked about the portrayal of woman in Andy Warhol's films before Women in Revolt was released. In a press conference in Berlin for Trash (the previous film directed by Morrissey for Warhol) a journalist brought up the subject of Valerie Solanas. Bob Colacello was in attendance and later recalled the press conference in an issue of the Village Voice.

Bob Colacello ("King Andy's German Conquest," Village Voice, March 11, 1971:

Saturday, February 20, Berlin:

Once again a press conference and luncheon, this one distinguished by a rising stallion carved of butter as the centerpiece of the standard buffet of herring and hams and by a particularly strident group of women journalists determined to pin evasive Paul and quiet Andy down to some concrete statements of intent and meaning.

As the questions got tenser - "Why do women appear as vamps in your films?" "Why are all women stupid in your films?" "Mr. Warhol, was it also a comedy when you were shot by Valerie Solanis [sic]?" - the sun rose higher and higher, glaring down into the Hilton Roof Garden like a bright inquisitory lamp in a Nazi torture scene out of the some post-war movie. Andy seemed increasingly confused and afraid, trapped, but when it was over, to the surprise of everyone, he asked the most persistent and probing journalist of all, a dramatic old woman in red, for her name and phone number in the event he returned to Germany to make a film. "Me in a film," she shrieked, "but I'm a journalist." "Ohhh, but You're so good" said Andy, affirming his belief that actors are everywhere, that personality is all that matters.

A small group of women demonstrated against the film the day after it premiered in New York (see section 6 below).

4. PIGS, Sisters and Women in Revolt

Women in Revolt went by various names before it was actually released as Andy Warhol's Women in Revolt. As pointed out by Gavin Butt in his essay "Living the Dream in Women in Revolt," when the Village Voice announced that Warhol/Morrissey's new film would be called "PIGS" the "public reaction was so bad that they decided to change it to "Sisters." (Butt's essay appears in Glyn Davis and Gary Needham (eds), Warhol in Ten Takes (London: BFI/Palgrave Macmillan, 2013), p. 185)

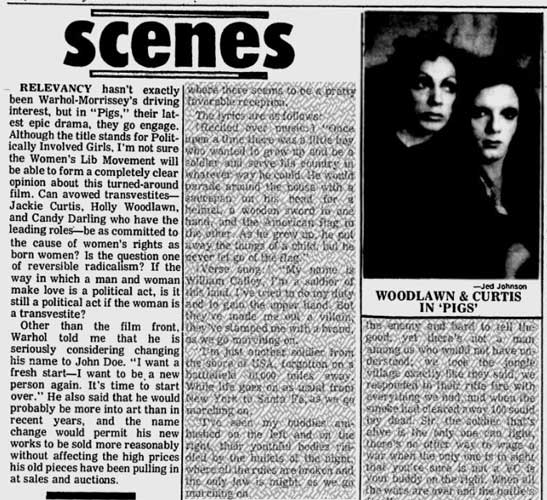

Howard Smith, "Scenes," Village Voice, April 1, 1971 referring to the new film as "Pigs"

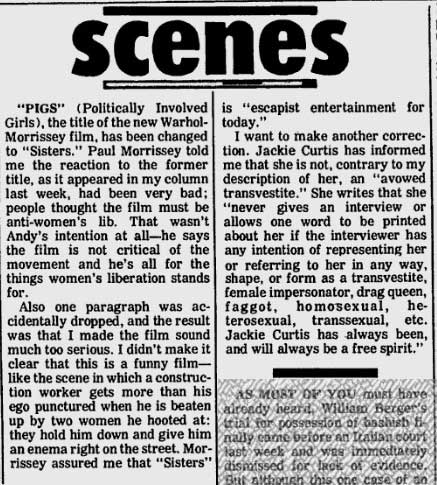

Howard Smith "Scenes" Village Voice, April 8, 1971 referring to the new film as "Sisters"

Despite the name change, the acronym PIGS was used in the film as the name of the woman's liberation group that Jackie, Holly and Candy belonged to. The fact that PIGS was an acronym linked it satirically to Solanas' group which was also an acronym - SCUM or the Society for Cutting Up Men.

In her biography of Valerie Solanas, Breanne Fahs draws a link between comments made by Solanas in real-life and lines that appear in Women in Revolt.

Breanne Fahs (Valerie Solanas: The defiant life of the woman who wrote SCUM (and shot Andy Warhol) (NY: The Feminist Press at the City University of New York, 2014), p. 99:

In 1967 Valerie and Andy spent time together at Max's Kansas City musing about things she had on her mind while he held court over his emerging group of superstars. He listened to Valerie's statements and then put some of them into his movies, which infuriated Valerie. "He would give the lines to Viva and Valerie told him to stop it and he kept doing it," a friend recalled. Valerie repeatedly told Andy to stop stealing her lines, but he refused, continuing to to feed them to different - and perhaps more conventionally attractive - female stars he surrounded himself with. Many of her lines appeared in Women in Revolt, clearly without her permission or approval. She often was angry at Andy, but he just shrugged her off, attributing her reactions to eccentricity.

Fahs, however, does not indicate which of the lines in Women in Revolt were borrowed from Solanas and the source of her information is third generation - the drag queen editor (Donny Smith) of the underground newspaper DWAN recounting what he was told by Valerie's ex-boyfriend, Louis Zwiren, who was recounting what Solanas originally told him. (p. 343 fn. 82 and 83).

5. When was Women in Revolt filmed?

It's difficult to pinpoint the exact start and end date of the filming. According to J. Hoberman, at least one of the scenes in Women - the exterior shot where "Jackie and a feminist comrade (Prindeville Ohio) retaliate against a taunting construction worker (Frank Cavestani) by attempting to administer an enema" - was filmed as late as March 1971, although the film first went into production in March 1970. (LT39-41) The July 29, 1970 issue of Variety reported that the film was "already in the can." (LT39). The is a signed release from Holly Woodlawn dated March 1970. (Jim Hoberman, "Women in Revolt: Late, Last, or Post Warhol?," The Late Work of Andy Warhol (NY: Prestel Verlag, 2004), p. 42.

According to Holly in her autobiography, A Low Life in High Heels, she shot her first scene in the Spring of 1971. This seems unlikely if she signed a release in 1970. In an interview that appeared in the November 15, 1970 issue of the New York Times, she says "I've already done another movie for Paul and Andy. It's called Women in Revolt, and it's about the Women's Lib movement. I play a Lesbian - but badly." (Guy Flatley, "He Enjoys Being A Girl," New York Times, November 15, 1970.)

In her autobiography, Holly also says "Shortly after Women in Revolt had wrapped production, I was back riding the publicity wave of Trash, and it was a tsunami! I was making guest appearances at colleges and universities and had been invited to appear at that film's opening in Atlanta." (p. 190)

There is an advertisement and a review of Trash playing at the Broadview Cinema in Atlanta in the January 4, 1971 issue of an Atlanta underground newspaper called The Great Speckled Bird, but no mention of a public appearance by Holly. (The newspaper was founded by New Left activists from Emory University and members of the Southern Student Organizing Committee, an offshoot of Students for a Democratic Society.) There is, however, an interview with Holly in a later issue of the newspaper - dated March 1, 1971. Holly says in that interview that she is in Atlanta to visit her boyfriend Johnny who lives there. (Johnny played the high school student in Trash whom Holly shoots up with heroin after telling him to trust her - "no needles." They were in a relationship in real-life.) The blurb at the end of the interview says that Women in Revolt has already been "completed."

Given that that more than one source mentions that Women in Revolt had been completed by Spring of 1971 and that it was completed by the March 1, 1971 issue of The Great Speckled Bird, it is likely that Holly's first scene was filmed earlier than Spring 1971. Since there is a 1970 release signed by Holly, it may have been as early as Spring 1970. In any case, it appears that the film was shot over a long period of time from about March 1970 through March 1971. According to Jackie Curtis, it took 2 1/2 years to make Women in Revolt, although this is most likely an exaggeration.(PS272) It probably just seemed that long because of the drug-fuelled chaotic lives of Jackie and Holly at the time. However, there was a two year period from when shooting (probably) began in about March 1970 and its New York premiere in March 1972. By the time of its premiere, Morrissey/Warhol had already finished filming another film, L'Amour. (See Andy Warhol's L'Amour)

In Holly's March 1971 interview in The Great Speckled Bird, the interviewer begins by explaining that "Holly Woodlawn, the 'drag queen' who played Joe's girlfriend in Trash, was in town last week and Carter and Ron and I went down to the Regency to get an interview." At the end of the interview, referring to Trash, he asks Holly if she made a lot of money from the film. The note about Women in Revolt being completed follows Holly's response to the question.

Smokey Kaufman, "Holly Woodlawn," Great Speckled Bird (Atlanta, Georgia), March 1, 1971, p. 7

The full interview, with photographs of Holly, can be read here. The article refers to Women's in Revolt as a "Warhol film."

6. The opening of Women in Revolt and the demonstration against it

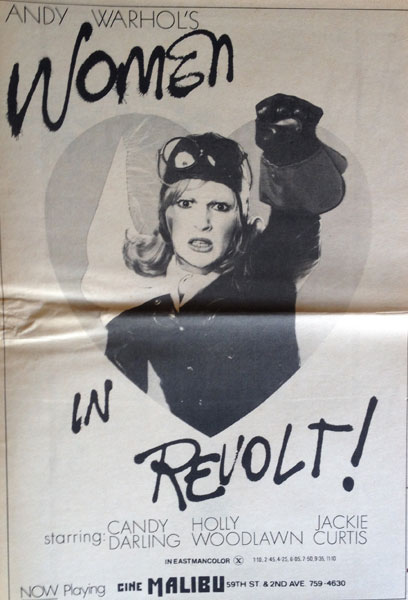

When Women in Revolt opened at the Cine Malibu in New York on February 16, 1972, it was advertised as "Andy Warhol's Women in Revolt." The prominence of Warhol's name probably had more to do with marketing than anything else. Hoberman claims that the film also played L.A. previous to its New York opening.

J. Hoberman:

Announced in Variety's July 29, 1970 issue as Women in Revolt, directed by And Warhol and "already in the can," the movie had its world premiere as Sex, 15 months later in a midnight screening at the Los Angeles Film Festival; it then opened on December 17, 1971 at the Cinema Theater in Los Angeles as Andy Warhol's Women and, on February 16, 1972, at the Cine Malibu in New York now (again) Women in Revolt.(Late works, p. 39)

It's unclear, however, where Hoberman got his Los Angeles dates from. I have found no advertising for the L.A. presentations of Women in Revolt and Bob Colacello does not mention the L.A. screenings in Holy Terror:

Bob Colacello (Holy Terror, p. 84-85):

Despite weekly screenings at the Factory all fall of 1971, Women in Revolt still didn't have a distributor. Nobody would touch it, not Cinema Five, not smaller art-film distributors like New World Films; even the Germans were wary. Andy decided to rent the Cine Malibu, a small sexploitation movie house on East 59th Street, and we launched the run with a celebrity preview on February 16, 1972.

Women in Revolt ad in the March 1972 issue of Interview magazine (Warhol Film Ads)

The fact that the film was a satire of the womans' movement may have contributed to the difficulty in getting a distributor, particularly because of the link with Valerie Solanas. Some women's liberationists had sympathized with Valerie. Ti Grace Atkinson, the head of the New York branch of the National Organization of Women initially supported Solanas but Betty Friedan the national head of NOW wanted nothing to do with her. In the end it was Valerie who rejected them, accusing Ti Grace in a letter sent on February 27, 1969 of using her (Valerie's) case to "receive the widespread recognition that you've been grovelling and sucking after for the past 8 or 9 months" and effectively accusing the women's movement of having stolen her ideas. (Fahs, p. 191)

A small group of women demonstrated against the film the day after it opened in New York, according to Bob Colacello.

Bob Colacello (Holy Terror, 1990, p. 86):

The next afternoon [after the premiere], about a dozen women in army jackets and peacoats, jeans, and boots were outside the Cine Malibu waving protest signs. Vincent [Fremont], who stood beside the ticket booth counting the customers to make sure that Andy Warhol Films, Inc. wasn't cheated, called the Factory to describe the scene, and I called Candy. "Who do these dykes think they are anyway?" she joked. "Well, I just hope they all read Vincent Canby's review in today's Times. He said I look like a cross between Kim Novak and Pat Nixon. It's true - I do have Pat Nixon's nose."

Although Canby was kind about Candy, he wasn't so kind about her co-stars, Holly Woodlawn and Jackie Curtis. Canby wrote that Holly is "very funny in short takes, and, in longer ones, so grotesque that it's difficult to watch her." About Jackie, he wrote that she "reminds me a good deal of an Elizabeth Taylor stripped of that fabulous face..." (Vincent Canby, "Warhol's 'Women in Revolt,' Madcap Soap Opera," New York Times, February 17, 1972). In his review, Canby also credits Andy Warhol as the director of the film, with Paul Morrissey the executive producer.

7. Candy Darling vs. Holly Woodlawn vs. Jackie Curtis

After Women in Revolt, the three drag queens who starred in the film (and who had known each before the film was made) - Candy Darling, Jackie Curtis and Holly Woodlawn - were often mentioned together as a comedic threesome who continued to be friends on and off-screen. But, in real life, there was quite a bit of rivalry between them which Holly later wrote about in her autobiography:

Holly Woodlawn (The Holly Woodlawn Story: A Low Life in High Heels (NY: St. Martins Press, 1991) p. 242-43)

After Women in Revolt we had nothing in common except for the press, which was forever linking us together as Warhol's transvestite trio and comparing us to the stars of the Forties. Candy was always compared to Lana Turner because she was the seductive, glamorous blonde! Jackie was the hardened, take-it-on-the-chin Joan Crawford type; and I was the loose, full-lipped chiquita comedienne, which somehow earned me a combined comparison to Phil Silvers and Marlene Dietrich! Ain't that a pisser? As far as I was concerned, I was the next Hedy Lamar and no one could tell me any different!

In the eyes of outsiders, we were the Andrews Sisters of the Underground. I would have loved it if it were true, but he fact is after we each attained our Superstardom, we became competitive rivals and couldn't stand one another most of the time."

[end]

Gary Comenas, warholstars.org, 2022 (An earlier version of this essay is available on request.)