Jerome Hill and Charles Rydell cont.

by Gary Comenas (2016)

page two

Warhol, Taylor Mead and other Warhol stars also visited Hill and Rydell at their home in Bridgehampton. Gerard Malanga refers to a visit there in the summer of 1971 in the description of a photograph on the Christie's auction house website. Malanga is quoted as saying, "We took the train to Bridgehampton to visit our friends Jerome Hill and Charles Rydell at Hill’s home, ‘Windy Hill’. Taylor Mead (who starred in several films by Warhol and other ‘underground’ filmmakers) is sitting in a chair, waiting for his close-up, and I’m coming through the door, clutching my Nikon in one hand and something else — maybe another camera — in the other. Paul Morrissey was there, too." ("Gerard Malanga on Polaroid — ‘The Friendly’ Camera")

When in Manhattan, Hill and Rydell lived at the Algonquin and continued to host dinners there. Bob Colacello recalls that Hill hosted an "off-to-Cannes" party there in May 1972. (BMB496) (BC112)

Colacello writes, "Parties, parties, parties, all winter, all spring, all night" before going on to describe the premiere of Cabaret, the premiere of Holly Woodlawn's film A Scarecrow in a Garden of Cucumbers and then Jerome Hill's "off-to-Cannes" party at the Alonquin.

Bob Colacello:

Jerome Hill's off-to-Cannes party at the Algonquin, where Andy, William Burroughs, Terry Southern, and Larry Rivers sat in a row, like some Mount Rushmore of Hip, and Brigid Berlin burst in with a radio broadcasting Nixon's massive bombing of Hanoi. Everybody said it was the end of the world, except Burroughs, who had already passed out, and Andy who was deep into dessert - a "snowball" of ice cream covered in coconut and vodka. (BC112)

Jerome Hill Films

Hill was off to Cannes because his film, Portrait (aka Film Portrait) was going to be screened at the Festival de Cannes. The film had been chosen to be part of the "Directors' Fortnight" lineup that year. (Hill also owned property in Cassis in the south of France - see below.)

The B.F.I. lists Hill as the director of the following films:

Grandma Moses (1950)

Albert Schweitzer (1956)

The Sand Castle (1961)

Open the Door and See all the People (1963)

Death in the Forenoon or Who's Afraid of Ernest Hemingway? (1966)

The Canaries (1968)

Merry Christmas (1969)

Film Portrait (1972)

In addition to the Cannes tribute, Film Portrait was also selected as "an outstanding Film of the Year for presentation at the 1972 London Film Festival and won the Gold Dukat Prize at the 21 st Annual Film Festival in Mannheim." (MAC9) Art writer, Mary Ann Caws describes the film:

Mary Ann Caws (Jerome Hill: Living the Arts, Jerome Foundation, 2005, p. 21):

The film seems to speed by, reflecting one of Jerome's tenets for vitality in his work: for him, everything that flutters seems full of life, as opposed to what is static. All the different aspects of his life, some filmed by others, some by himself, compose this portrait. It is clearly not meant to be an autobiography of the usual sort, in which the moments would be presented in a more chronological order. It is a portrait of himself in a moment, and at moments - more than an evolution of a personality. In this experimental film, which is widely accepted as a masterpiece of the avant-garde, the avant-garde filmmakers with whom he associated, in particular Brakhage and Broughton, were highly influential.

Hill's films were documentary in nature, often employing experimental film techniques. His short documentary, Grandma Moses, was nominated for an Academy Award in 1949. (MAC9) Another documentary, Albert Schweitzer, received an Academy Award in 1957. (MAC10)

Caws notes that "From 1956 to 1960, Jerome made the semi-narrative film The Sand Castle, based on the ideas of Carl Jung. Subsequent films included the full-length Open The Door and See All the People, also related to Jung's thoughts; and four hand- painted animation shorts, Anticorrida, Merry Christmas, The Artist's Friend, and Canaries. (MAC10)

Hill's film, Death in the Forenoon or Who's Afraid of Ernest Hemingway, also incorporated animated figures.

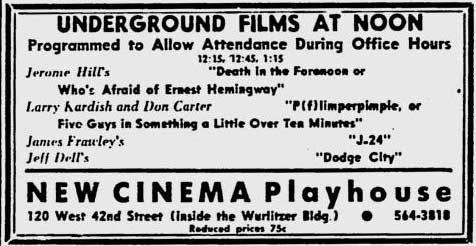

Village Voice ad for a screening of Hill's film in the December 14, 1967 issue, p. 48

Nanci Bialler reviewed the film in the Vassar College newspaper.

Nanci Bialler ("Underground Movies, Mekas Films Varied, Absorbing," Vassar Miscellany News, vol. LI, no. 23, Poughkeepsie, NY, May 3, 1967:

... Death in the Forenoon, or Who's Afraid of Ernest Hemingway, by Jerome Hill, was a clever and slick combination of photography and animation. To a thirty-year-old film of a bullfight, Hill added semi-abstract animated figures who dashed about the ring trying to shield the bull from the matador. In his use of vivid colors, rinky-dink music, and sparclty of animation, Hill set a furious pace which transformed the slow stateliness of a bullfight into a light comedy. He mocked both the institution of bullfighting and the efforts of the pseudo-Humane Society.

In addition to his filmmaking, Jerome was also an accomplished painter, particularly while residing at his home in Cassis in the south of France.

Cassis

In 1939, Hill purchased a property known as "La Batterie" in Cassis, France. Eventually he also bought the building across the street - formally known as the Hôtel Panorama. (MAC8)

Cassis had been recommended by one of his teachers, Othon Friesz, at the Académie Scandinave in Paris where Hill had studied painting for three years. Jerome had graduated at the age of 17 from the Saint Paul Academy and then, for five years, attended Yale where he studied music. After Yale, he went to the British Academy of Painting in Rome for two years before enrolling at the Académie Scandinave. (MAC6)

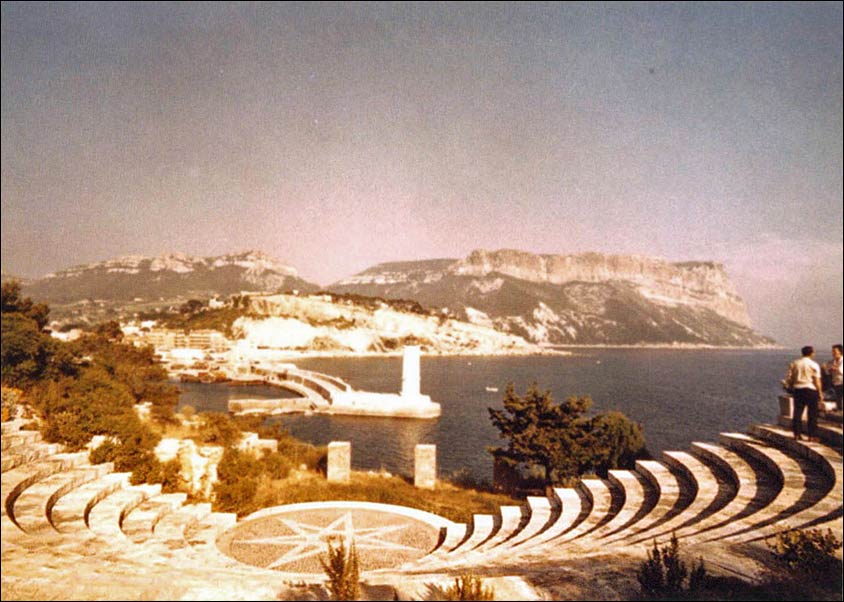

Othon Friesz described the geography of Cassis as an "alternation of layers of stony chalk and gravel forms, thanks to the declivities, breaks, and geologic slidings, recognizable silhouettes of all shapes and sizes. What shows up "large on the slopes of Cap Canaille is repeated on the cliffs of the Château de Cassis as well as on the rocks of Bestouan. Everywhere there is a single theme, richly varied. From the summit of the mountains (right after Carpiagne, and before the descent into the amphitheatre where Cassis is situated), the immense sweep of waves of stones appears in all its majesty... (MAC7)

Hill organized a festival in an amphitheatre in Cassis on a regular basis. According to the author of The Living Theatre: Art, Exile, and Outrage, the amphitheatre was "built by Jerome Hill." Originally called the Theatre de la Mer it later became known as the Jerome Hill Greek Theatre.

Mary Ann Caws recalls, "In that theatre, he arranged over the years, for an elaborate Cassis town festival. Over and over, the theatre was used, for Shakespeare's The Tempest and other spectacles... Once he arranged for an appearance by The Living Theatre with Julian Beck and Judith Malina." (MAC14)

The Living Theatre

Theatre de la Mer (Jerome Hill Greek Theater), Cassis, France (MAC5)

The Cassis performance of The Living Theatre is the one that took place in late July 1966 which was famously heckled by Warhol star Taylor Mead.

From The Living Theatre: Art, Exile, and Outrage (London: Methuen Drama, 1997) by John Tytell:

In July, the [Living Theatre] company drove through the Alps, returning to Reggio Emilia to continue working on Frankenstein and to spend the hot nights under mosquito netting. At the end of the month, after packing the sets of The Brig and Frankenstein, the company boarded their old, beat-up buses for a long drive along the Mediterranean coast to Cassis in Provence. There, they were met by poet Taylor Mead and the film maker Jonas Mekas, and quartered in unfinished buildings meant for French Algerians. In the nagging wind of the mistral - reputed to drive people mad - surrounded by stone-pocked hills, they performed Mysteries under the sky in a stone amphitheatre built by Jerome Hill, their host, the black sheep of an American railroad family, who had given the company $20,000 to help pay for their 1962 European tour. Taylor Mead found the performance "communal to the point of sameness." He was irritated by the frequency with which Julian kept repeating "End the war in Vietnam!" and began shouting "A bas les intellectuals!" and "Vive la guerre de Vietnam!" in response.

Under a full moon, near the sea, they did an extravagant five-hour version of Frankenstein. The local newspapers parodied the company, maligning them with implications of drug use, but the curious audiences still came. As usual, there were supporters as well as unsympathetic observers, one of whom filled a hubcap with gunpowder and left it under one of the buses. Fused and detonated, it fortunately did little damage but existed as an ominous sort of warning.

The organizers of the festival at Cassis permitted the company to stay on for an additional three weeks, and in the middle of August, with the mistral wind bending the trees and one of the buses leaking oil because of a faulty piston, they drove to Berlin. (JT216-17)

Jerome Hill and Jonas Mekas

Jonas Mekas later recalled filming the Living Theatre's performance of Mysteries at Cassis, although he didn't release the film at the time.

Jonas Mekas:

I filmed The Living Theatre's Mysteries in 1966, at the Festival de Cassis, organized by Jerome Hill. I didn't like the results and I never released the film, but I always liked the segment based on MacLow's script. Maclow's version differs slightly from The Living Theatre's version. You can find MacLow's script in Kastelanetz's anthology called Scenarios. MacLow says he wouldn't have said some of the things the Living Theatre said. Noel Burch helped me to record the sound. (JMF)

Mekas later released at least some of the Living Theatre footage in his film, Street Songs (1966/1983) which is currently available from the Film-Makers' Coop. (JMF)

Hill also appeared in a number of films by Jonas Mekas: In Between: 1964 - 68 (1978), Birth of a Nation (1997) and Notes for Jerome (1978). Mekas describes Notes for Jerome as follows:

Jonas Mekas:

During the summer of 1966 I spent two months in Cassis, as a guest of Jerome Hill. I visited him briefly again in 1967, with P. Adams Sitney. The footage of this film comes from those two visits. Later, after Jerome died, I visited his Cassis home in 1974. Footage of that visit constitutes the epilogue of the film. Other people appear in the film, all friends of Jerome: Taylor Mead, Bernadette Lafont, Charles Rydell, Barbara Stone and David Stone and their children; Noel Burch, Judith Malina and Julian Beck and the Living Theater collective, Ms. Chaliapin, Jean Jacques Lebel, Michael Fontayne; Alec Wilder, P. Adams Sitney and Julie Sitney and Jerome's perhaps closest and oldest friend, whose name I forgot, but whom he always called Rosebud. The soundtrack was practically all recorded during the same period, during the same visits to Cassis. Piano improvisations are Jerome's and Taylor Mead's; the soloist (Monteverdi's 'Lasciatemi morire!' and Giordani's 'Caromioben') is Charles Rydell's practicing, in Cassis; the ocean and most of the wind is the late summer mistal; and so are the cicadas, street music, scooters, motorboats, birds, and my own sing-songing. The text of my Lithuanian 'song' is, in translation, 'the sun is setting, the sky is red, I am sitting by the sea and I am singing by myself.' Those were lonely summers for me, I thought a lot about home. That's why this film, this elegy for Jerome is dedicated 'to the wind of Lithuania.' Sometimes, though, I had a feeling that Jerome was as much of an exile as was I. (JMF)

Mekas also shot a 4.5 minute film in Cassis called Cassis (1966) which is described in the Film-Makers' Coop catalogue as "A small port in South of France, a lighthouse, the sea, shot from just before the sunrise until just after the sunset, all day long, frame by frame, a frame or two every second or every few minutes."

Hill and Mekas were connected both artistically and financially. Film scholar, Paul Arthur, writes in his essay "Routines of Emancipation: Alternative Cinema in the Ideology and Politics of the Sixties" that "Mekas relied on several 'angels' such as Jerome Hill and publisher Harry Grant to underwrite the costs of commercial space or the printing of Film Culture, but virtually all outside funding was garnered ad hoc." (DJ26)

Film Culture was the film magazine that Mekas published and the "costs of commercial space" were presumably related to Mekas' various cinematheques and his the Film-Makers' Cooperative during the 60s. (See "Jonas Mekas and the Film-Makers' Cinemathque.")

In 1970 Hill was involved in the founding of the Anthology Film Archives with Mekas. According to film scholar, David E. James, the Anthology was to be "a permanent home where the classic works of film could be shown on a regular basis. Jerome Hill, P. Adams Sitney, Peter Kubelka, Stan Brakhage, and Mekas himself drew up plans for such a museum, to be called Anthology Film Archives. A selection committee made up of James Broughton, Ken Kelman, Peter Kubelka, Jonas Mekas, and P. Adams Sitney were to establish 'The Essential Cinema,' a permanent collection of "the monuments of cinematic art.' Unlike Mekas' previous screenings, the Anthology was from the beginning critical and discriminatory." (DJ12) (See also: "Jonas Mekas and the Film-Makers' Cinematheque," p. 6.)

Jerome Hill R.I.P.

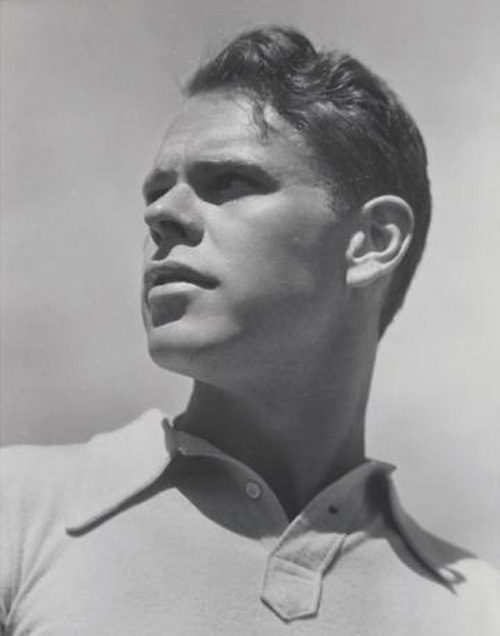

Jerome Hill (1931) (Photographer: Edward Weston)

Collection Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona © 1981 Arizona Board of Regents (MAC)

("Living the Arts," Jerome Foundation, 2005)

Two years after the founding the Anthology Film Archives, Jerome Hill died at St. Luke's Hospital on November 21, 1972. He was sixty-seven years old. (MAC17) Charles Rydell retreated to the Hamptons but later returned to New York and appeared in video projects by Andy Warhol and Vincent Fremont.

After Jerome's death, Jonas Mekas paid the following tribute to him in the Village Voice, December 7, 1972 and re-published it in the No. 56-57 (Spring 1973) issue of Film Culture:

A POET IS DEAD (IN MEMORY OF JEROME HILL) by Jonas Mekas

Only four weeks ago, Jerome Hill’s film ‘Film Portrait’ was screened at the Museum of Modern Art, and he was there himself to talk, to answer questions. He was thin and white. Very few people knew it, but he knew it, and his close friends knew it: Jerome has been ill, very ill. He collected his strength to come to the screening, to see his friends, to see the screen sing for the last time. The film was beautiful, the projection was beautiful, and the screen sang. Jerome received an enthusiastic and warm reception for his film. It was a perfect, beautiful crowning of a very humble life of a very great artist.

No, Jerome Hill didn’t receive proper recognition during his life. From his friends, yes: Stan Brakhage, Peter Kubelka, P. Adams Sitney, James Broughton, a few others saw his work and praised it and told him what a great artist he was. ‘Film Portrait’ will remain among the masterworks of cinema-a masterwork of form, of treatment of an era, an extraordinary work of animation and color. I cannot go into all its values and all its beauties here. But the film critics, during his life, they looked at Jerome, they looked at his work, and they could’t see it: they saw his grandfather’s railroads behind him, instead; they discussed the railroads, and the money, and they missed the colors and the movements and the glories of cinema. And so one more artist is gone, and now we can begin to praise his work! Will it always be the same? Why can’t we praise our living artists! No, Jerome won’t add a single frame now, he made his last film.

One of the extraordinary things about Jerome was that while everybody around him was getting older with the years, Jerome seemed to get younger and younger. His work got younger and younger every year. His cinema began at Warner Brothers, and it ended in the lines of avant-garde film. His progress was slow and painful. He had to free himself from many society, family and commerce traditions. But he was freeing himself and opening himself continuously, until, in the early ‘60s, his search brought him into the lines of the avant-garde film. After that, he seemed to discover his own style, and he threw himself into the making of the ‘Film Portrait’, his crowning achievement. His films and his paintings exploded with little bursts of ecstasies.

Simultaneously with his own creative work, he became very sensitive to the creative work of other film artists and he did everything to assist their work. Probably nobody will ever know the extent of help he has given to independent film-makers; because of his humility, practically all help was given anonymously. But I can tell you this much, that neither the Film-Makers'’ Cooperative nor the Film-Makers’ Cinematheque nor Film Culture magazine nor the Anthology Film Archives would exist or be what they are, if not for the kind help of Jerome Hill, who came always just at the right time, whenever our heads were sinking below the water line; without pampering-but never letting us down in real need. The whole movement of the American avant-garde film of the ‘60s would have taken a completely different turn, much slower and thinner, without the help of Jerome. I am not writing here a history of the American avant-garde film; I am writing a last tribute to Jerome. So I am talking in very general terms, and I am skipping details and names and figures. But when such a history is written, that history will be dedicated to Jerome Hill.

But now Jerome is gone, his body. The American avant-garde film is a chapter in the history of cinema, a fact of cinema, a reality of cinema that cannot be turned back. The cinema will never be the same again. And a long line of works of great beauty has been created. A form of cinema exists vaguely known as the avant-garde film, that will have to be discussed, analyzed, taken into account by whoever makes cinema, teaches cinema, or looks at cinema. Will there be another Maecenas for the art of cinema, for avant-garde film? Will there be anyone to whom we’ll be able to turn in real need? The creation of art and the Maecenas of art go hand in hand. An artist, in order to create, doesn’t need a wide acclaim and a wide audience: give him two or three friends, one critic, and one Maecenas, and he’ll produce great works and he’ll expand the vision and ideals of humanity.

Yes, it’s very possible that we are at the end of a great period of creativity in American cinema; it’s very possible that Jerome Hill’s death marks the beginning of another stage of the American avant-garde film: the stage of preserving for posterity what has been created. It was the genius foresight of Jerome that he thought about that too: during the last three years of his life he put himself completely behind the creation of the Anthology Film Archives, a place in which the works of American avantgarde film-makers can be preserved and seen in their full glory. Yes, even here, Jerome was younger than many of us: he was in the future. He knew that it’s not enough to create, no: taking loving care of what has been created, taking care of the flowering fruits of the human spirit, which is art - he knew that that was the other side of the matter, and they both made One. Such was the work and wisdom of Jerome Hill. But death has its own wisdom. Jerome Hill died on November 21, in the afternoon, in St. Luke’s Hospital. Upon his wish, he was cremated. A small funeral service was held for family and friends at St. James’s Episcopal Church, Madison Avenue at 72nd Street, at noon on November 24.

to page three

(Brigid Berlin and Charles Rydell)