Andy Warhol Pre-Pop

by Gary Comenas (2006)

page three

Warhol's exhibition at the Hugo gallery was sparsely attended. James Fitzsimmons wrote a short review in Art Digest, noting that the work had an "air of precocity, of carefully studied perversity." (1) David Mann, the gallery manager, recalled that Truman and his mother did attend the exhibit, although does not say anything about Warhol meeting Truman at the time. Mann would later work for the Bodley Gallery which would host three exhibitions of Warhol's work from 1956 - 1959.

David Mann:

"Very few people came because it was pretty much the end of the season... I remember that Truman came and looked at them... he came with his mother. They both liked them very much... The next thing I knew, Andy told me he'd won some kind of poster contest. I think it was for NBC, a series of programs they were doing against drugs. He did one of his black and white drawings. They used that and that kind of shoved him to the forefront. He started his series of shows with me [at the Bodley Gallery] which I loved doing, but they were always kind of crazy." (2)

The poster that Mann referred to sounds like the illustrations that Warhol did for a CBS Radio program on organised crime. See "Andy Warhol - 'The Nation's Nightmare.'"

ALBUM COVERS

Warhol would continue to do album covers throughout his life - the most well-known being the 1967 Velvet Underground album featuring a banana and the 1971 cover for The Rolling Stones' album Sticky Fingers, co-designed with Craig Braun, which featured an image of a man's crotch in a pair of jeans with a functioning zipper. The Nations Nightmare was probably the first album cover featuring Warhol's work. Coincidentally, it dealt with the use of recreational drugs - a theme that would often be associated with Warhol and his entourage throughout the 1960s as a result of films like The Chelsea Girls which showed Brigid Berlin shooting up speed on camera. Warhol would also became known for his use of transvestites in his films. In approximately 1952, the same year that he won the award for The Nation's Nightmare, Warhol also did some of his earliest drawings of a man in drag when he sketched the photographer, Otto Fenn, dressed as a woman. Warhol's drawings were similar to photographs that Fenn had taken of himself dressed as a woman.

OTTO FENN

Otto Fenn

Self-Portrait in Drag (ca. 1952/4)

According to Fenn, Warhol was a regular visitor to his studio in mid-town Manhattan.(5) Fenn had dabbled in art prior to concentrating on photography and had also designed sets for theatrical productions. He had photographed the collections in Paris after World War II and had worked as an assistant to Louise Dahl-Wolfe.(6) In addition to sketching Fenn, Warhol also drew butterfly images which were then projected onto the faces of models for a series of fashion photographs taken by Fenn in 1952. Later, during the 1960s, Warhol would achieve a similar effect during performances of the Velvet Underground by projecting his films onto the musicians and dancers onstage. He would also use projections on the faces of Nico and Eric Emerson in his film, The Chelsea Girls. Fenn eventually retired to Sag Harbour where he ran an antiques shop prior to his death. (7)

LIMITED EDITIONS

When Warhol wasn't sketching friends, he was busy doing commercial illustrations - or trying to get new commissions. One way that Warhol attempted to insure that his name was remembered when art directors were commissioning illustration work was to give them quirky gifts or one of his self-published portfolios which he began producing in 1952.

Tina S. Fredericks:

Almost every visit was accompanied, Japanese style, by a gift. Usually it was carefully wrapped in tissue and came in the ubiquitous brown paper bag. Around Easter there were eggs, wonderfully painted - by his mother, he said - in traditional complicated, colourful Ukrainian patterns. Sometimes it was a little book: One of those printed by Seymour Berlin in editions of a hundred or so copies - sometimes as many as two hundred - and hand-coloured in brilliant washes by friends he was apparently already recruiting to 'help,' as they were later to do in his famous 'factories.'" (8)

The promotional books were limited editions. As the early numbers of a print run of limited editions are more desirable than later numbers, Warhol often purposefully mis-numbered the books. According to Nathan Gluck who had first met Warhol soon after the artist arrived in New York (9) and would work as Warhol's commercial assistant beginning in 1955 (10), "Andy got the idea that everybody wanted to have low numbers. So, he never kept track of the numbers. So he would arbitrarily just write numbers: 190, 17, 16 and so on." (11) One of the earliest of these portfolios was There was snow in the street and rain in the sky, consisting of 18 unbound pages in ink and pencil.

THERE WAS SNOW IN THE STREET AND RAIN IN THE SKY (1952)

There was snow in the street and rain in the sky was a collaborative effort. Warhol did the illustrations while Ralph T. Ward (Ralph Thomas Ward) provided the words. Warhol had been introduced to Ward, who went by the nickname of "Corkie," by George Klauber at a Christmas Eve gathering at Klauber's Brooklyn apartment. Klauber later remembered how the festive gathering was interrupted by the police after Klauber hurt himself while dancing in his underwear.

George Klauber:

"I had taken my trousers off and Ralph and I were waltzing wildly around and crashed into a table and when I got up I had this big gash in my side so we called for an ambulance, which meant the police would come too. Andy got quite sick with apprehension and flew the scene. He was just really terrified. Of course to the cops it was apparently a gay party and they thought somebody had stabbed me." (12)

According to Klauber, "Andy was very upset and left immediately, but waited downstairs for Ralph, thinking that he and Ralph could go off together. Unfortunately for Andy, Ralph came with me to the hospital..." (13) Klauber thought Andy had a crush on Ralph but that Ralph thought Andy was a "boorish peasant." (14) Ward later recalled he and Andy did have "a love affair" but that he (Ward) was never really attracted to him. (15)

Klauber was also indirectly responsible for Warhol taking on an agent for his commercial work. One of the recipients of Warhol's promotional gifts was Klauber's boss, Will Burtin. In 1952 Warhol drew an arthritic hand for a medical pamphlet designed by Burtin for the Upjohn Company. When, in Spring 1953, Warhol arrived at Burtin's office to give him a hand painted Easter Egg, Burtin introduced Warhol to Fritzie Miller who would later work as Warhol's agent.

BEN SHAHN

The Upjohn pamphlet cover that Warhol illustrated for Burtin in 1952 incorporated his blotted line technique and was similar to work being done at the time by another graphic artist, Ben Shahn. Shahn was an exception in the commercial art world. Not only was he a successful illustrator, he had also achieved success as a fine artist. According to George Klauber, Ben Shahn had done a lot of work for Upjohn and "they looked upon Andy as a cheaper Ben Shahn." (16) Shahn, like Warhol, had also done work for CBS.

Shahn's work was known at Carnegie Tech when Warhol was a student there. Warhol's classmate Bennard B. Perlman remembered that an instructor, Sam Rosenberg, had taught them about Shahn during their junior year and had told the class about the Shahn retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. (17) When Warhol was asked in 1978 who his "favourite or "most memorable teacher" was at Carnegie Tech, Warhol answered, "Hmm. Sam Rosenberg."17b Another classmate, Jack Wilson, recalled that Andy mentioned Shahn to him with "great admiration." (18) Ted Carey, who later worked as Warhol's assistant, thought that the work of Warhol and Shahn had "a strong similarity."

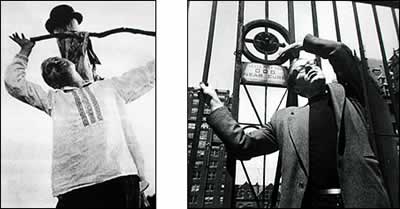

Andy Warhol (right) strikes a (Ben Shahn) pose (ca.

1952)

(Shahn photographer unknown/Warhol by Leila Davis Singeles)

Ted Carey:

"The only person at that time who had a line that looked like that [Warhol's blotted line]... was Ben Shahn. And Ben Shahn and Andy... their work had a strong similarity, and, in a way, they were very competitive... I can remember once Andy was doing some theater work - and I don't remember if it was a poster or some costume design - and, if I can remember, it was for the Spoleto Festival, but I'm not absolutely sure. And in some way, Ben Shahn was involved, whether it was as a judge or he had some sort of influence deciding whether his [Warhol's] work would be used or not. And, as I can remember, he more or less put Andy down because he was more of a 'commercial artist' rather than a 'fine artist' which is kind of interesting now because I think Andy is much more recognized and more famous than Ben Shahn... But, anyway... I don't think the work was used." (19)

Shahn, like Warhol's first New York roommate, Philip Pearlstein, was a Realist painter. He also worked for some of the same commercial clients as Warhol. Peter Palazzo, who would later use Warhol for the I. Miller account beginning in 1955, had earlier worked as the art director for American magazine, published by the U.S. government for circulation overseas. According to Palazzo he first met Warhol "around 1950 - 51," when Warhol did "a few drawings" for the magazine. Palazzo thought Warhol's work "had a style and a technique that was very reminiscent of Ben Shahn," but that Shahn was "a lot more expensive" than Warhol and, in any case, was "not available" at the time. (20)

One reason that Shahn was more expensive than Warhol may have been because he was considerably older and had already earned an impressive array of artistic credentials by the early 1950s. Born on September 12, 1898 in Kovno, Lithuania, Shahn had immigrated to Brooklyn in 1906, serving as an apprentice in a lithography shop in Manhattan while attending high school. He had his first solo exhibition at the Downtown Gallery in New York from April 8 - April 27, 1930, consisting of mostly African subjects. He had traveled extensively in Europe and North Africa for approximately three years during the 1920s. In April 1932 he had another exhibit at the Downtown Gallery which featured his paintings based on the controversial Sacco - Vanzetti court case. (21)

SACCO AND VANZETTI

Bartolomeo Vanzetti and Nicola Sacco were Italian immigrants who were involved with anarchist groups in the U.S. On June 2, 1919, a suicide bomber, Carlo Valdinoci, blew himself up outside the home of the U.S. Attorney General, A. Mitchell Palmer. Sacco and Vanzetti had traveled to Mexico two years previously with Valdinoci and were rumoured to be involved with the bombing. On April 15, 1920, two thieves killed and robbed two employees of the Slater & Morrill Shoe Company, who were carrying a payroll of $15,776.51. On September 11, 1920, Sacco and Vanzetti were indicted for the murders and they were brought to court on May 31, 1921. Although the testimony of some of the witness was called into question by the defence, they were both convicted of the murders and sentenced to the electric chair where they met their deaths on August 23, 1927. (22)

Shahn's series of gouache paintings based on the case were exhibited at The Downtown Gallery in New York from April 5 - 17, 1932 as "The Passion of Sacco and Vanzetti." The same year, Shahn also did another series of paintings based on the trial of Tom Mooney, a labour leader who had been convicted of bombing a "Preparedness March" in 1916 - a march suspected of being organized by factory owners who would benefit from increased spending on munitions. Previously, in 1930, Shahn had also painted watercolours based on The Dreyfus Case. Some of Warhol's artwork from his college days and his early years in New York is reminiscent of both Shahn's style and political subject matter - such as Untitled (Huey Long) (1948/49) and Communist Speaker (ca. 1950).

F.B.I.

The political nature of Shahn's work and his involvement in progressive organizations, brought Shahn to the attention of the FBI. A September 1952 FBI report indicated that he had been under surveillance for some time:

From the FBI report on Ben Shahn:

"A review of the Bureau's files reflects a long history of Communist Party front activity on the part of the subject, continuing to the present time. It is observed that the subject has been identified with the following Communist Party front groups, among others: Southern Conference for Human Welfare in 1947; the publication Jewish Life in 1948; Civil Rights Congress in 1948; National Council of Arts, Sciences and Professions in 1948 and 1950; Scientific Cultural Conference for World Peace in 1949; Young Progressives of America in 1949; American Lab or Party in 1950; New Jersey Committee for Peaceful Alternatives in 1951 and 1952." (23)

Shahn and his employer at the time, CBS, were openly criticized in the July 25, 1952 issue of the Counterattack newsletter - a reactionary "hate sheet" which was founded in 1947 by three ex-FBI agents in order to expose the names of Communist sympathisers. Counterattack argued that CBS had run an ad with an illustration by Shahn to publicize the television network's coverage of the Democratic and Republican conventions and that Shahn had previously contributed artwork to Communist magazines and was involved with organizations sympathetic to the Communist cause. CBS and their sponsor, the Westinghouse Electric Corporation, were therefore guilty, by hiring Shahn, of aiding Communism. The editors of Counterattack urged their readers to write to CBS and Westinghouse to ask them to justify their "carelessness in helping to finance a leading, continual supporter of Communist Party causes." (24)

Although the president of CBS, Jack Van Volenburg, defended Shahn as "one of the greatest living painters," the network eventually agreed to withdraw Shahn's work from future ads and another artist was hired to replace Shahn. (25) The same year (1952) Andy Warhol won the Art Directors Club Medal for the Shahn-like illustrations he did for CBS for The Nation's Nightmare. Although he tended to avoid political controversy whenever possible, Warhol would, in 1968, also come under investigation by the FBI over his film, Lonesome Cowboys.