Art is a Jealous Lover: May Wilson: 1905-1986

by William S. Wilson/November 18, 2001

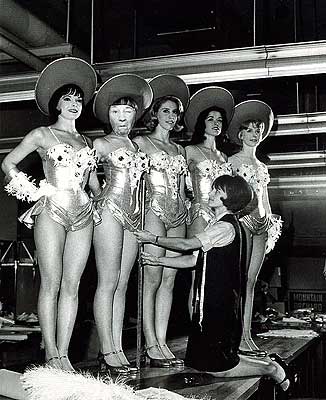

Untitled collage by May Wilson from her Ridiculous Portraits series (1968-1972)

May Wilson, because she was not beautiful, was not exempted from necessities and adversities, as beautiful people often are. An axiom of her life was that people had to earn their way, perhaps doing as she had done about 1920, leaving high-school after her first year to go to work at a ten-hour-a-day job, while fitting in a class in art at night school. Even though she paid for the course with her earnings, and paid her mother $5.00 a week for room and board, her family made her quit the course. Yet she worked her way from an uneducated poor family into marriage with a lawyer and motherhood of two educated children. By 1948 she lived as an artist on a ten-acre gentleman's farm north of Towson, Maryland.

With an odd large nose, her peculiar appearance won her nothing, but she took prizes in swimming and dancing. She understood the power of youthful beauty, but because it was unearned, and not an achievement, she did not respect it. Without beauty, or even prettiness, she nevertheless sought to be an object people would gaze at. However when seeking attention from her strenuous efforts, she sought it on her terms, whether for sewing clothes, crocheting rugs, cooking and canning food, gardening organically, making wine, or painting the walls of the house. These activities, with so many skills in her unglamorous hands, prepared her for tentative work with photography just after World War II, and then for courses she took by correspondence in studio art and in the history of art.

By 1951 her two children were out of the house, so she began showing her paintings, then also teaching painting to neighbors, among them farm-folk who paid very small sums. She sold work for a few dollars, trying to earn enough money to pay for supplies like paint and glue, while not exploiting students or collectors. Her family was somewhat bewildered, even disappointed. People who assumed that she aspired to the upper middle-class had expected that social ascents would improve her conduct. But she rarely was driven past a country club without taking a cigarette out of her mouth to curse it. Even American entertainments began to bore her.

Instead of conforming to her social and economic sphere, with each social move she became more outrageous. Gradually she moved herself out of her economic class, positioning herself as an artist, a person who subordinates social class by working toward achievements in accord with self-set standards. By the age of fifty, she reached the goal she had announced as a small poor child in Baltimore: she was an artist. Her communication with family and friends became a summoning toward art, or nothing.

Wilson had always known that she was not going to be seen the way other women are seen, because of her unusual nose, probably broken in childhood. While she might wear a touch of lipstick, she never wore rouge or eyeliners. When she began painting, she used her body, arms, hands and whole torso to paint pictures from her shoulder, not to embroider from her wrists. She stopped wearing girdles and high-heels, or anything which constricted even social movement. Thus her work as an artist increased her vigilance about women as they fictionalize themselves by twisting their appearances to fit male assumptions. She had always despised beauty parlors, and campaigned intensely against them among her family and friends. She wanted the attention of men without making herself conventionally attractive, intent on being verbally interesting for talks, and visually interesting for looks.

When Wilson became aware that her husband was attracted to a younger woman, she began to pay more attention to how she looked when she was with her husband. But she had left their marriage to follow her art. Her children and her grandchildren were welcome to follow her, or they could wave good-bye. As I have often had reason to say, art is a jealous lover. Later she admitted that she had left her husband for art before he had left her for the other woman. Still, she had been called a gargoyle, and suffered the fury of the scorned. During her sixtieth birthday weekend she was with her husband for their fortieth wedding anniversary, but she was also with her friend Ray Johnson, there in her studio by the Chesapeake Bay. She was already cutting into sexy photographs of young women.

Wilson, whose arms and hands were probably stronger than her husband's, sliced the centerfolds from Playboy magazine, folded them many times, then scissored patterns into the folds. Then, when unfolded, the centerfold revealed a pattern like a doily or a snowflake. Thus an airbrushed pornographic picture was overwhelmed by an abstract pattern of holes cut into the image of a woman. From her perspective, she subsumed an insensitive photograph, with no aesthetic vitality, into a formal composition in which an abstract pattern animated an image from a belabored sensuality. If she saw that pornography was negating her, then with her scissors she both negated that negation, and got more home-made material for her art.

The snowflaked image was sometimes glued down over an old collage, but more often was glued down over another centerfold. One picture had holes through which selected parts of the other picture were visible. Then every decision about form in relation to important parts of the images had inadvertent random effects. No matter what formal relations she made between two pictures, she had to accept some chance of uncontrollable effects. Thus the collages came to represent her experience, because she had been working to accept such randomness in existence, as with her practice of Zen meditation. Thus her precise order, as an intentional pattern with some unintentional effects, was an image of real life which she was teaching herself to believe in. By obeying her self-set rules, she learned that her autonomy produced results that were beyond her control.

Within this process, Wilson could let her co-conscious mind work tacitly. She never articulated the ideas implicit in the image of a sixty-year-old woman mutilating photographs of young women. These collages served two purposes at the same time. In terms of content, her determined forms overwhelmed sensual immediacies with abstract patterns. In terms of expressiveness, the tensions between the controlled patterns and their uncontrollable effects conveyed her feelings about how she was teaching herself, after sixty years in her old life, to produce more new life for herself.

Wilson wrote to me in 1965, "...not to mention my paper doilies which have become more complex and also have possibilities. I pasted some over the collages which are effective." I mailed her cheap postcards of show-girls. Then her friend Ray Johnson mailed to her a book of male pornography. Ray sometimes would take two of an identical pair to make them different, and sometimes he would make two different objects into a mismatched pair. Nothing in his correspondences ever corresponded precisely. Thus he was fully himself when he encouraged her to work with both females and males, for pornographic photographs of men and women were not symmetrical. The pictures of women were for men, and the pictures of men were for other men. "I had a great time with the girlie cards you sent. I need a booklet of nude, or nearly so, girl, for paper doily cut-outs. boy too. Ray sent book of muscle man which I used. love what I did."

Ray's gift was in line with his trick of dividing one into two, and mashing two into one. Because the book he sent pictured the same man in different posses, she could collage two pictures of one man into one picture: "If you get around 42nd St. please send me some muscle-men booklets. The one Ray sent was a booklet of the same man, so there was a cut-out of him on top of a whole page of him" (06/15/1965).

When Wilson moved into the Chelsea Hotel in June, 1966, she was ready with "doily cut-outs," or "snowflakes," easing her transition from Maryland to Manhattan. She soon taped or pinned paper works to the wall, rendering a bare room in a hotel into an elaboration of themes from her studio in Maryland. Later, after moving into an apartment at 208 West 23rd Street, she usually hung a few suggestive works, sometimes in the bathroom, as clues to what was permitted in visual and verbal investigations.

Perhaps only repression and self-censorship were not permitted. The clues and cues in her apartment gave a young person permission to discuss topics which were not conversational, but also gave Wilson license to ask questions which went beyond the bounds. As Ray Johnson used to say, "Oh, when May Wilson makes her first incision..." Johnson preferred a question to be less an investigative probe than a method of making a link across a surface with other links. Note that his image of incision conveys an idea of cutting into. While he might paint over a magazine page, Wilson might scissor holes into it. Ray was always bringing attention back to surfaces, away from inscrutable depths, while May often tried to cut through surfaces, probing to discover or to reveal whatever was underneath.

Wilson had her own motives for associating herself with gay men. She was an outsider to a gay male sensibility, yet even more of an outsider to a dominant American male sensibility. By also working with erotic pictures of women printed for men who wanted to see available women's bodies, she matched the socially acceptable desire of some men for women with the socially unacceptable desire of other men for men. Her intellectual wit is evident in her double play. She made two groups, quite unequal in power, appear equal in their relations with sexy photographs. Since she was in her art to the homosexual the same as she was to the heterosexual, thereby gay men and straight men had something in common: May Wilson. She entered herself into each half an equation: May Wilson + gay = May Wilson + straight. Her acceptance of one argues for acceptance of the other, because either both were insiders, or both were outsiders. Under the cover of her formalism, she smuggled mischief by neutrally weighing homosexual and heterosexual pornography in the balance, and judging them to be just about equal - brothers under the skin.