Abstract Expressionism 1980s+

by Gary Comenas (2009, Updated 2016)

Ibram Lassow: "I remember the times long ago when Bill [de Kooning] and I would wonder what it would be like to be well known. What a strange thing that he became an internationally famous artist, and the irony is that now he doesn't even know. Now he paints and eats, and that's all." (AW)

1980

1980: Irving Sandler is appointed as a trustee of the Mark Rothko Foundation. (IS337)

Irving Sandler:

In 1980, I was appointed as a trustee of the Mark Rothko Foundation. This came about as a result of the most notorious court case in the annals of the American art world... Within weeks of Rothko's death, the [Mark Rothko] Foundation sold 100 paintings to the Marlborough Gallery at bargain prices and consigned to it 698 other works. The result of this step was to enrich Frank Lloyd, the gallery owner, and his cohorts. Rumors of questionable dealing soon spread throughout the art world, and Herbert Ferber, the trustee for Rothko's children, blew the whistle. The upshot was a notorious court case... Judge Millard Midonick, who presided over the case, decreed that five-ninths of the estate would go to the Foundation and the remainder to Rothko's children... The Marlborough Gallery was kicked out of the Art Dealers Association. The judge also dismissed the Foundation's board and appointed new trustees of impeccable reputation; among them were Donald Blinken, Dorothy Miller, Gifford Phillips, Emily Rauh Pulitzer and Jack Tworkov.

When Tworkov retired from the board, I was appointed to replace him. The continual problem we faced was deciding what to do with some 160 paintings from Rothko's mature period, 200 earlier 'surrealist' works, and 690 miscellaneous items, including drawings, sketchbooks, and small studies. I suggested that we meet with leading art professionals and solicit their advice. The board agreed, and I invited museum directors Robert Buck (Albright-Knox Art Gallery), Martin Friedman (Walker Art Center), Henry Hopkins (San Francisco Art Museum) and Sherman Lee (Cleveland Art Museum). I also invited Arne Glimcher, the owner of the Pace Gallery, which represented the Rothkos' estate, Professor Richard Turner, Director of New York University's Institute of Fine Arts, and Brian O'Doherty of the National Endowment for the Arts and a friend of Rothko's. We informed them that a number of Rothko's acquaintances believed that it was his intention upon his death to have his works sold and the proceeds to be spent helping older artists in need. However, there was nothing in his will to indicate this...

In the end we decided not to sell any works. We favored museums that had shown an interest in Rothko's painting while he was alive, and gave them clumps of his work. We also did this because many of Rothko's works in our possession were not of the highest quality and were only useful for study purposes... When the National Gallery of Art offered to create a study center and to become a clearinghouse for other museums, we readily accepted and gave it the bulk of the Foundation's pictures... (IS337-9)

May 1980: Philip Guston retrospective at the San Francisco Museum of Art. (MM210)

It was Guston's second retrospective. A previous retrospective had taken place at the Guggenheim in 1962. The second retrospective consisted of more than one hundred paintings and drawings and traveled to Chicago, Denver, Washington and New York. Guston, weakened from his heart attack in March 1979, flew to San Francisco with his wife for the opening. They were joined there by their daughter, Musa, and her family who had traveled from their home in Ohio.

Musa Mayer [Guston's daughter]:

On my parents' flight out from New York, I found out later, my father had been breathless and pale - they had given him oxygen. But once we were safely in San Francisco, the momentum of the week took over... My father seemed pleased with the installation of his work. We strolled through the galleries where final touches were being put on the show... The earliest painting there, Mother and Child, painted in 1930 when my father was only seventeen, had been cleaned for the first time... Having grown accustomed to its orangy-yellow appearance, the product of fifty years of cigarette smoke, we expressed shock at its raw, vivid colors. My father smiled at our reaction. "It's just as I remember it," he said...

He stopped before a painting from the early fifties. "You know, I remember what I ate that day, when this picture finally came off," he said. It was in the old Cedar Bar days. I had a studio on Tenth Street. I went in the bar and Bill de Kooning was there with Franz Kline. I'd been on the picture for two or three weeks and... I had this look on my face, I guess, because Bill said to me, "Good strokes, eh? You made some good strokes." (MM212)

A film crew who were shooting a documentary on Guston followed the family as they made their way through the exhibition. When asked about his change of style, Guston replied "You know, comments about style always seem strange to me - 'why do you work in this style, or in that style' - as if you had a choice in the matter... What you're doing is trying to stay alive and continue and not die." (MM213)

Musa Mayer:

At the museum, my father collapsed after a particularly strenuous morning and was brought back to the hotel. I found him stretched out, gray and sweating, in a darkened hotel suite, his restless brown eyes set so deeply in their dark sockets they appeared like a mask of his own invention, the skin of his face puffy and florid... He didn't want a doctor, he said. They'd hospitalize him, he knew, and he'd seen quite enough of coronary care units. No, he only wanted a drink, and to rest... The opening was at the end of the week, the day before we left... When it was time for my father to talk he spoke of his happiness, his gratitude for the exhibition. In his gracious way, he thanked the museum, the corporate sponsor, his dealer, his wife, and his friends. And finally, unexpectedly, he thanked me. Feeling that intense beam of his love from across a sea of tables, I was overwhelmed with tears... (MM215)

June 7, 1980: Philip Guston dies.

After returning home from San Francisco, Guston had another heart attack while having dinner at the home of Fred Elias and his wife who owned several of Guston's paintings. "He just put his head down and was gone," Fred told Guston's daughter the next day. (MM219)

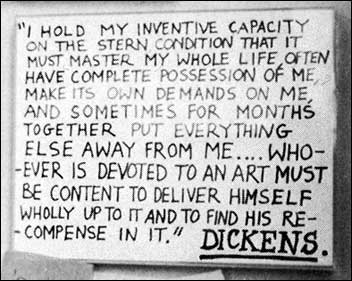

A Charles Dickens quote in Philip Guston's writing that Guston kept on his studio wall

Musa Mayer [Philip Guston's daughter, 1988]:

Beside the glass double doors to my father's studio is a green curtain for privacy, so that no one would walk in on Philip when he was working. Though no one is here but me, I find myself instinctively pulling the curtain across the entryway, hearing the brass rings scrape along the metal rod. Still protecting him. I open the curtain again, reach for the lights, and pause for a second look.

The studio walls are bare, with only ladders and light fixtures leaning up against them to disturb their white expanse. Big wooden packing crates for a European exhibition now past, built sturdy as furniture and lined with green felt, are stacked like giant blocks. Stretched, primed canvases stand side by side, waiting. For a year or two, we cleaned in here, but now everything carries a fine coat of pale blond dust.

We call this room 'the studio,' but it is no one's studio now. No longer steeped in sadness, it is too anonymous for that. It is no longer his. It's just a room, an empty room. It could be anyone's space, with its flat lights, its silences, its dust.

I listen to the high whine of the fluorescent lights, the beating of the silence behind. So this is what death is really, I think, what it becomes. Beyond the pain of loss, there is finally only this sense of absence. (MM247)

1980 - 1987: Tom Ferrara works as Willem de Kooning's assistant. (DK503)

1981

1981: Willem de Kooning's daughter, Lisa, begins building her own house on the grounds of her father's studio. (DK593)

1981: Willem de Kooning revises his Will. (DK621)

A new Will was executed in 1981 after Elaine de Kooning came back into Bill's life. The new Will stipulated that his estate would go to Elaine and Lisa on a 50/50 basis. If Elaine died first, everything would go Lisa and Elaine's heirs would not be entitled to anything from the estate. (DK621)

April 1981: Arshile Gorky retrospective at the Guggenheim.

Willem de Kooning and Elaine attended the show with Tom Ferrara. (DK589)

Spring 1981: Willem de Kooning starts painting again. (DK588)

At the age of seventy-six years old, de Kooning started to paint again. He would produce fifteen paintings during 1981 and twenty-eight in 1982. (DK591)

Joan Levy [a friend of de Kooning's daughter]:

When he started doing those paintings of the eighties, the light was pouring out. He said, "What do you think?" I said, "They're so ethereal. It looks like you died and went to heaven." De Kooning agreed. "Yes, that is what I was going for." (DK591)

According to de Kooning biographers Mark Stevens and Annalyn Swan, "He began to draw less than he had in the past. Now, he would make an initial drawing on the canvas itself, and then use recently completed paintings to stimulate his eye. He would lift passages from paintings with charcoal and tracing paper (as he had often done in the past), which he would then transfer to other pictures. 'It was like the process of of making collages,' said Ferrara, who watched de Kooning move the tracing around until it worked with the picture." (DK591)

De Kooning often listened to music while painting. His assistant, Tom Ferrara, later recalled one time when Ferrara put on a record of classical music and a song by Rossini came on. According to Ferrara, "He [de Kooning] stumbled out with both hands full of palette knives and brushes and said, with tears in his eyes, 'Who put that on? God bless you!" De Kooning still loved Stravinsky as well, and would also listen to jazz and some current bands, particularly the Talking Heads. (DK594) He also listened to the Beatles. His attorney's daughter (Linda Eastman) had married Paul McCartney in 1969. Elaine de Kooning would tell a journalist in 1982 that "Paul and Bill are very chummy. Paul and Linda always come to visit us when they're in East Hampton." (DK596) Ferrara said that de Kooning told him that during one of his hospital stays it was his birthday and he felt that everyone had forgotten him "until Paul and Linda called to sing him Happy Birthday." (DK596)

De Kooning would work during the day and watch television at night. According to Ferrara, "He always liked advertising. A lot of times on TV he would comment on the commercials. I think he enjoyed the fact that advertising was so straightforward." (DK595) He would usually be in bed by 10 pm, although often had trouble sleeping and would, according to Ferrara, "pace through your room hoping you'd wake up." (DK594) A friend of Elaine's brother was staying in the studio one night and woke up in the middle of the night and saw de Kooning standing in the doorway with his fist in his mouth and tears running down his cheeks. (DK594)

November 3-December 12, 1981: "Krasner/Pollock: A Working Relationship" at the Grey Art Gallery, New York University.

1982

1982: Dedication of the Motherwell Gallery at the Bavarian State Museum of Modern Art, Munich.

Motherwell lectured at the University of Munich. Excerpts were published in Die Kunst in June 1983 and the complete text published in Munchner Jahrbuch der Bildenden Kunste in 1983. (HM)

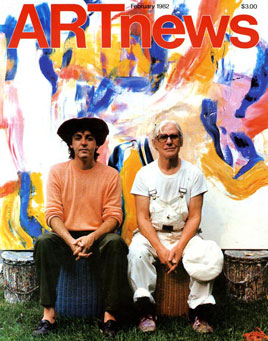

February 1982: "Willem de Kooning: I Am Only Halfway Through" by Avis Berman is published in the February issue of Art News.

The cover of the February issue of Art News featured a photograph of de Kooning seated next to Paul McCartney. It was taken by Paul's wife Linda (Eastman) McCartney who was the daughter of de Kooning's lawyer, Lee Eastman. The author of the article, Avis Berman, made a veiled reference to de Kooning's faltering memory.

Avis Berman [From "Willem de Kooning: I Am Only Halfway Through," Art News (February 1982)]:

One way de Kooning preserves his artistic resources is through an avoidance of self-consciousness and a disciplined amnesia that seems essential to any sort of sustained personal vision. (As Cézanne wrote, a painter must 'produce the image of what we see while forgetting everything that has appeared before our day.') Asked if a wriggling biomorphic line that appears in a few of his recent paintings is an allusion to his early close friend Arshile Gorky, de Kooning answers, "Well, I don't know. In a way I have him on my mind all the time. But I forget what the paintings - his and mine - look like at a certain point." Later he remarks, "Artists themselves have no past. They just get older." (BE70-1)

February 20 - March 11, 1982: "Robert Motherwell: A Selection From Current Work," at M. Knoedler & Co. (BE11)

March 1982: Willem de Kooning attends the premiere of a documentary about his life and art.

De Kooning on de Kooning was part of the "Strokes of Genius" series, hosted by Dustin Hoffman, which also included documentaries on Franz Kline, Jackson Pollock, Arshile Gorky and David Smith. Charlton Heston introduced the film at the Kennedy Center in Washington. De Kooning also received a second Presidential Medal of Freedom on the trip - he had lost the first one. (DK596)

April 1982: Willem de Kooning attends a White House dinner in honour of Queen Beatrix of the Netherlands. (DK596)

March 17 - May 1, 1982: Exhibition of Willem de Kooning's new work, "New Paintings: 1981-1982," at the Fourcade, Droll Gallery. (DK592)

Ten works of art were exhibited. John Russell reviewed the show in the April 16th issue of The New York Times:

John Russell:

These are "late" paintings, inasmuch as [de Kooning] may no longer have energy to burn in the way that he had twenty years ago. But in place of almost ostentatious energy there is a new spareness of statement. Even five years ago, he would not have shored up the composition as he does today, with big battens of paint that bring the kind of balance we expect in a shipyard. (DK592)

September 4, 1982: Jack Tworkov dies.

Tworkov died in Provincetown, Massachusetts at the age of 82. From 1948 to 1953 he and Willem de Kooning had adjoining studios in Manhattan. (JT)

From his obituary in The New York Times:

Mr. Tworkov was best known for the flamelike brush strokes and controlled rhythms of his Abstract Expressionist paintings. He worked by building up blocks and fields of color and then playing the blocks, brush strokes and fields against one another, so that at their best the paintings became force fields in which everything seemed alive... In his recent quiet, meditative work, shown at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum this summer, Mr. Tworkov seemed to have turned his painting inside out. While in the 1950's he seemed to create pictorial structure by raging against it, in the recent work, with its clear dependence on geometry and line, he seemed to create feeling by embracing structure. The two sides of his work were reconciled and inseparable. "Subtle and extremely refined" Barbara Rose, the art historian, said of Mr. Tworkov: ''He was a marvelous, marvelous person and a marvelous painter. He was an Abstract Expressionist, but he remained quite European in his orientation. His was a subtle and extremely refined art.'' (JT)

December 4, 1982: Frank Lloyd, the owner of the Marlborough Gallery, is convicted of tampering with evidence in Rothko trial.

Lloyd, a British citizen aged 71, was convicted by a jury of three men and nine women in the State Supreme Court in Manhattan of "tampering with evidence" during the 1971 Rothko lawsuit. He had altered "the stock book in which the gallery recorded the history, including the buying and selling price of each of the paintings in its inventory." (ML) Sentencing was set for January 6, 1983. Lloyd could get four years in prison on each of the three counts in the indictment, but remained free on a $1 million personal-recognizance bond until sentencing. (ML)

1983

1983: Robert Motherwell retrospective exhibition at the Albright -Knox Gallery, Buffalo, New York.

The exhibition included 100 major works. (HM)

1983: Willem de Kooning finishes fifty-four paintings. (DK602)

Willem de Kooning's output during the 1980s was prodigious, considering that prior to 1981, he would sometimes work on one canvas for several years. According to his assistant, Tom Ferrara, "He knew that he was at the end of the line. He was conscious of it and would sometimes joke about it." (DK603)

Helping de Kooning was a staff of assistants and helpers arranged by Elaine de Kooning. His canvases were stretched for him, meals were prepared for him and thousands of dollars worth of paint was put at his disposal. During 1983 and 1984 Elaine tried to help him further by indirectly suggesting new colours for him too use. According to de Kooning biographers, Mark Stevens and Annalyn Swan, she "asked Ferrara to open tubes of new colors and put them on the large worktable that de Kooning used as a palette," but "de Kooning would have none of it." (DK604)

As paintings were finished they were catalogued and stored. The core staff included Tom Ferrara, Robert Champman and conservator Susan Brooks. Elaine's personal assistant, Larry Castagna was also often there, as well as his housekeeper Gertrude Cullem. Lee Eastman and his son John remained his lawyers and Frances Shilowich his accountant. (DK603)

January 6, 1983: Frank Lloyd, owner of the Marlborough Gallery, is sentenced in the Rothko case.

After being convicted of tampering with evidence in the Rothko trial (see December 4, 1982 above) Lloyd was ordered by the State Supreme Court in Manhattan to donate $100,000 to the Fund for Public Schools and permit students to tour his Manhattan Gallery whenever a new show opened. The Gallery agreed to arrange the tours and provide guides at no cost to the schools. The assistant district attorney who tried the case, John J. Rieck Jr., called the sentence "extraordinarily lenient" and said that the settlement would not be a hardship for Lloyd who had a net worth, according to Rieck, of at least $50 million. Reick had argued for a prison sentence for Mr. Lloyd. Lloyd denied any wrongdoing. (MP)

May 1983: Exhibition of de Kooning's sculpture in "The Complete Sculpture: 1969-1981" at Fourcade, Droll.

The rubber molds for the original sculptures done in Rome by de Kooning had been destroyed so Fourcade enlarged photographs of the originals using an overhead projector and persuaded de Kooning to authorize larger versions of the works to be done by the Tallix Foundry in Peekskill, New York. Bob Spring the director of the Modern Art Foundry later said "Fourcade and Eastman decided to make some money. They were selling the little ones for a high price, and I don't think de Kooning cared." (DK605) The new sculptures sold well and Elaine de Kooning authorized a new edition of one of de Kooning's Rome pieces, Untitled #2, which was cast by the Gemini foundry in California in sterling silver in an edition of six. (DK604-5)

May 1983: Art dealer Allan Stone buys Willem de Kooning's Two Women for $1.2 million.

Stone would sell the painting one year later for $1.9 million. (DK604)

October 1983 - January 1984: "Lee Krasner: A Retrospective" at Houston Museum of Fine Arts.

Krasner's first major retrospective was organized in conjunction with The Museum of Modern Art. She traveled to Houston in October for the opening. She had been living in her apartment on East Seventy-ninth Street with crippling arthritis making it difficult to paint or walk. Sometimes she could be spotted in Central Park in her wheelchair being wheeled by one of her nurses. (JP254) To friends who congratulated her on the exhibition she commented "Too bad it's thirty years too late." (JP254) After returning from Houston she "took to her bed" and never painted again. Her assistant, Darby Cardonsky would sit next to her and read her reviews to her. (JP255)

December 15, 1983: "William de Kooning: Drawings, Paintings, Sculpture" opens at the Whitney Museum of Modern Art.

De Kooning, Elaine and Tom Ferrara flew to New York the night before the opening in Steve Ross's private helicopter. Ross was head of Warner Communications and his future wife, Courtney Sale, had produced the De Kooning on de Kooning documentary the previous year. Warner Communications underwrote the show of de Kooning's drawings that accompanied the main de Kooning exhibition. (DK605) The de Koonings stayed at Lisa's new apartment on Wooster Street and attended an exclusive pre-opening party that night.

The next night was the official opening party which nearly two thousand people had paid $250 or more to attend. De Kooning was supposed to make an appearance but didn't. Instead he was represented by Elaine and Lisa. (DK605) The reviews of the show, which consisted of 250 drawings, paintings and sculptures, were mostly negative, with some reviews remarking that the show was focused too much on the artist's expressionistic side. (DK605)

1984

1984: During 1984 Willem de Kooning finishes fifty-one paintings. (DK602)

De Kooning finished the works with the help of Elaine and his numerous assistants.

1984: Conrad Fried films Willem de Kooning painting. (DK615)

Elaine de Kooning's brother Conrad filmed the 80 year old artist without his knowledge. (DK615)

June 20, 1984: Lee Krasner dies.

Stricken with arthritis Lee died of "natural causes." (JP254) She left behind an estate valued at $20 million. Her Will stipulated that her executors establish a foundation to help "needy and worthy artists." A small stone marks her grave next to her husband's, Jackson Pollock. (JP255)

July 22 - August 18, 1984: "Lee Krasner Memorial Installation" at The Museum of Modern Art.

Originally meant to be retrospective, the exhibition became a "memorial installation" after Krasner's death.

Late 1984 - 1985: Willem de Kooning paints a triptych. (DK612)

The triptych was for St. Peter's Church in New York City. An assistant pastor had read an article about de Kooning that had appeared in The New York Times Magazine on November 20, 1983 and was struck by de Kooning's comments on the Matisse Chapel at Venice in which he said "I'd like to do something like that if somebody would commission me to do it." (DK612-3) If de Kooning would agree to do the triptych for their church, the church would first display it and if the congregation approved, the church would seek a donor to come up with the $900,000 purchase price. (DK613) The finished triptych was titled Hallelujah and installed behind the altar of the church in the autumn of 1985. Seven weeks later it was removed after complaints from the congregation. (DK614)

1985

1985: Willem de Kooning paints sixty-three paintings. (DK602)

1985: Willem de Kooning shows symptoms of Alzheimer's disease.

De Kooning's housekeeper of twenty years, Gertrude Cullem arrived at the studio one day to find that de Kooning had strewn his clothes over his bedroom floor. Cullem later recalled, "I went downstairs and I said, 'Bill, do you want me to take these clothes to the cleaners?' He said, 'To the cleaners?' I said, 'Well, they're all over the floor.' He came upstairs and said, 'Did you do that?' I said, 'No. Why would I do that to your clothes?' He said, 'Well Gertrude. I think we'd better pick them up before they get wrinkled.' Really he was... you know, quite a ways then." (DK608)

From De Kooning: An American Master by Mark Stevens and Annalyn Swan:

De Kooning suffered a serious mental downturn in late 1984, followed by another the next year. He failed to recognize familiar faces and spoke less often, sometimes resorting to a private sign language of nods, claps, and gestures... In her attempt to keep de Kooning's lapses private, however, Elaine did not want this eccentric behavior discussed in the community... Now even old friends were discouraged from dropping by, which aroused their ire. They were instructed to call Elaine, who scheduled their visits and made sure that she was present when they arrived. Often, she did the talking for de Kooning. She also represented him in public... Elaine did not move in full-time with de Kooning. That left the job of caring for him to his assistants... Night duty could be hair-raising. One time in the mid-eighties said [de Kooning's assistant Robert] Chapman, he woke up after falling asleep in front of the television and saw de Kooning sidling up the stairs. He had a coffee cup in one hand and a bottle in the other, no doubt recalling the days when he poured alcohol into his coffee cup. But what was in the bottle was Ortho Brush-Be-Gone, a poison used to kill shrubs... A new assistant, Kathleen Fisher, was hired in 1985.. Fisher's tenure coincided with the period in which de Kooning's mental state began to decline precipitously. He appeared, she said, to have no short-term memory. He was noticeably silent around Elaine. If Elaine arrived he stopped whatever he was saying...

Even so, he had flashes of complete lucidity. About a month into her job, Fisher said, she and de Kooning were alone at the studio when Emilie ["Mimi"] Kilgore telephoned. "And all of a sudden here's this man who at that point I really thought was somewhat out of it - I didn't really think there was anything very much there," said Fisher. "Until they had this conversation that was 100 percent on the dot... That was my first clue that there was something really there." (DK608-10)

De Kooning had been exhibiting symptoms of memory loss for some time, but because he was also a binge drinker it was difficult to differentiate his sometimes strange behaviour from his alcoholism. As his dementia worsened in the 1980s, he actually managed to complete more paintings than he had during the 1940s/50s. In 1985, for instance, with the help of Elaine, he created an average of one painting every five and a half days. (DK612) According to Elaine's assistant Larry Castagna, people said "What is going on here? Is he becoming a factory?" (DK602)

Emile Kilgore recalled that Bill said to her in 1985 that he wanted to stop painting and she wrote down what he said: "They didn't like my work. They don't want me anymore. I didn't say anything, but I was going to quit anyhow. I don't need them. I can get all kinds of work - decorate apartments." (DK612)

1985: Elaine de Kooning changes colour(s).

Elaine succeeded in her efforts at adding new colours to her husband's palette. She had previously made attempts in 1983 and 1984 to suggest new colours for Bill by asking Tom Ferrara to open tubes of new color and leave them on her husband's work table which he used as a palette. At that time, De Kooning had ignored the tubes of paint. (DK604) But this time instead of just leaving open tubes of of paint for him, his assistants began to mix the colours he was already using to create new ones. (DK612)

Robert Chapman [one of de Kooning's assistants]:

We all started getting anxious that he was only interested in red, yellow and blue. For some reason his palette was becoming more and more limited.... Since he steered toward red, yellow, and blue still, we'd start setting up mixes of red, yellow, and blue so that they weren't the same red or cerulean blue that he had been using. It would be a little bit of deviation from one painting to the next. And then gradually we started introducing more and he seemed willing to try some. (DK612)

The paintings which the new colours appeared in included Untitled XIII and Untitled XX. The first incorporated a new shade of turquoise green and the latter a new purplish colour. (DK612)

October 1985: Exhibition of de Kooning's recent work from 1984 - 1985 at Fourcade, Droll. (DK617)

It would be de Kooning's last show at the gallery. (DK617)

1986

January 1986: The alleged driver of the car behind Jackson Pollock's car objects to accounts of Pollock's death.

While researching his biography of Mark Rothko, James E. B. Breslin was staying at the Gramercy Park Hotel and using the lobby telephone to arrange appointments. A man using the phone next to Breslin overheard his conversation and told Breslin that he was the driver of the car behind Pollock's car when Pollock ran into a tree and died and told Breslin that "none of Pollock's biographers had gotten the story right." He offered to be interviewed by Breslin but Breslin declined. (RO550)

1986: Willem de Kooning produces forty-three works of art. (DK619)

1986: Robert Motherwell is elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, Cambridge, Massachusetts. (HM)

1986: Exhibition of Willem de Kooning's work from 1983-1986 at the Anthony d'Offay Gallery in London. (DK617)

1987

1987: The de Menil Collection opens in Houston, Texas.

The $30 million private museum was located one block west of the Rothko Chapel. In order to preserve the character of the surrounding neighbourhood the de Menils bought it - four blocks of brick and wood frame houses - and had them painted the same shade of gray as the museum. (RO462/484)

1987: Willem de Kooning paints twenty-six paintings.

De Kooning's assistants would sketch de Kooning's drawings onto blank canvases for him with the aid of a projector, often combining parts of different drawings to add variety. One of his assistants, Robert Chapman later recalled, 'I tried to keep some sort of sense about them that would relate to what Bill was working on at the time."

Chapman also recalled that due to de Kooning's worsening eyesight, he would miss the edges of his pictures during the 1980s: "We'd give him a brush with some white and say, 'Fill in that area.'" (DK620) By late 1987 and 1988, the assistants would deal with the blank edges ("holidays") themselves. According to Chapman, "if it looked like from the surrounding paint that it was deliberately left, we'd either leave it or try to match the difference in tonality so that it didn't look like the same white all the way across." (DK620) The process was kept secret but done with apparently good intentions as it was believed that painting was keeping de Kooning alive. According to Tom Ferrara "The impulse was tremendous to help Bill in any way you could. The temptation was to be overzealous." (DK621)

According to another of de Kooning's assistants Tom Ferrara, de Kooning's dealer Xavier Fourcade would show up at the studio and discuss with Elaine and the assistants which paintings were finished - which ones Fourcade should take to hang. (DK617)

1987: Willem de Kooning's Pink Lady is sold for $3.63 million. (DK604)

April 28, 1987: Xavier Fourcade dies of AIDS.

Elaine de Kooning kept the information from her husband, fearing it would upset him. De Kooning never knew that his dealer had died. (DK618)

In the months prior to his death Fourcade sold $9.3 million worth of de Koonings. (DK625)

1987: Elaine de Kooning's health worsens.

Several years earlier Elaine had been diagnosed with cancer and one of her lungs had been removed at Thomas Jefferson University Hospital in Philadelphia. She kept her illness secret and most people were unaware of the operation. In 1987 she started to have problems with her surviving lung and developed severe emphysema and blocked carotid arteries. A tumour had also been detected near the back of her spine. (DK618)

June 1987: Tom Ferrara resigns from the de Kooning household due to health problems. (DK619)

1988

1988: Willem de Kooning paints twenty-seven paintings. (DK620)

1987/88: Elaine de Kooning authorizes a series of prints by her husband.

The drawings had originally been done for the tribute book to Frank O'Hara, In Memory of My Feelings, published by The Museum of Modern Art in 1966. Only three of the series were published in 1966 but because they had been drawn on Mylar the remaining seventeen drawings could also be run off as prints. Two editions were printed by the Limited Editions Club of New York - one was an illustrated book, the other a portfolio. De Kooning had never signed the drawings, however, and this diminished their value. At some point during the printing process his signature appeared on the prints. De Kooning's lawyer, Lee Eastman, stepped in and the print run was stopped and the signature removed. The final edition of the portfolio had a reproduction of de Kooning's signature on a separate page, followed by the prints. But there were no signatures on the prints themselves. (DK622)

July 1988: Elaine de Kooning attempts to change her husband's Will. (DK622)

De Kooning's 1981 Will stated that should Elaine die before her husband, John Eastman (the son of de Kooning's attorney, Lee Eastman) would become an executor of de Kooning's estate. Elaine arranged for a law firm to draw up a codicil to the Will which removed Eastman as an executor and made Lisa and her attorney would be co-executors. When Elaine first approached Bill with the change in July 1988 he refused to sign it. He threw the papers on the floor and told her "You want to take my home from me." But finally he gave in and Elaine, LIsa and Robert Chapman witnessed his signature. Eastman refused to accept the validity of the codicil arguing that de Kooning was not mentally able to make such a decision. He warned Elaine's solicitor that the matter would have to be decided in court. If there was a court case, de Kooning's dementia would become public knowledge at a time when he continued to paint works that were being sold for a considerable amount of money. In 1987 sales of his paintings had brought in more than $9 million. The codicil was never pursued and Eastman remained an executor. (DK623-4)

Late 1988: Elaine de Kooning is admitted into Sloan-Kettering for radiation therapy. (DK623)

1989

February 1, 1989: Elaine de Kooning dies at the age of 70.

At a memorial six weeks later at Cooper Union College in New York, her longtime assistant Edvard Lieber told a story about how when he and Elaine had been watching television together once, a Congressman's death was announced and his family had requested no eulogies. Elaine turned to Lieber and said, "When I die, I want tons of eulogies." (DK624)

Elaine's funeral took place in East Hampton with guests attending a gathering at Joan Ward's house afterwards. Two further memorial services took place on later dates - one at the Guild Hall Museum in East Hampton and another at Cooper Union in New York City. The Cooper Union memorial featured twenty-six speakers and lasted several hours. (DK624)

Willem de Kooning was never told that his wife had died.

February 11, 1989: Willem de Kooning's daughter, Lisa, and John Eastman file a court petition asking that de Kooning be declared mentally incapable of looking after his affairs. (DD)

Filing the court papers meant that de Kooning's medical, legal and financial situation was put into the public domain. Attached to the petition was an affidavit from a Dr. Frederick Mortati of Long island stating, "It would appear.... Mr. de Kooning suffers from Alzheimer's disease." (DD) Because Elaine de Kooning had been careful to limit visitors to de Kooning's studio and control the few interviews he gave during the 1980s as his medical condition worsened, it was the first time that many people in the art world became aware of how serious de Kooning's condition was. Details of the case appeared in the summer edition of Art News and was picked up by the Associated Press and reported in the New York Times in May and June.

Pierre G. Lundberg was appointed by the court to represent de Kooning as his guardian in the case. After visiting de Kooning in the Springs in March he told the court that "I could elicit no direct or meaningful response to any question I asked," although de Kooning could still shake hands, read from a paper and brush his teeth. (DK625)

After investigating de Kooning's finances, Lundberg objected to the amount being paid to Lisa from de Kooning's money. Not only was she being paid $300,000 a year, she was also using her father's money to pay her own income tax which came to an additional $75,000 or more per year. She had also borrowed $342,523 from de Kooning. Lundberg recommended that her payments be reduced to $156,000 a year. (AW)

When the New York Times covered the story in June they also covered some of the activities of de Kooning's daughter. They noted that "On May 3, 1985, Ms. de Kooning was cited in reports in several newspapers linking her to a Federal drug investigation of the Hell's Angels in which more than 100 members and associates of the motorcycle gang in a dozen cities were arrested... An affidavit filed in Federal District Court by Special Agent Mark Young of the F.B.I. said information gained through telephone taps indicated that Ms. de Kooning had a number of drug-related conversations with Hell's Angels members..." (AW)

Lisa was never prosecuted at the time however and her attorney later excused her action by saying, "when she was younger, she led a free-flowing, atypical life. She has never been accused of any wrongdoing. She's put it behind her. She's devoted to her family and her art. What she did in her youth is the past. This is the present. " (AW)

The New York Times article ended with a quote by the sculptor Ibram Lassow who had known Bill since the 1930s:

Ibram Lassow:

I remember the times long ago when Bill and I would wonder what it would be like to be well known. What a strange thing that he became an internationally famous artist, and the irony is that now he doesn't even know. Now he paints and eats, and that's all. (AW)

In August 1989 the Court decided in favour of Lisa. She and John Eastman were appointed co-conservators of de Kooning's estate. (DK626)

May 21, 1989: Willem de Kooning is admitted into Southampton Hospital for a hernia operation. (DK627)

c. July 1989: Willem de Kooning is hospitalised for prostate surgery. (DK627)

1990

1990: Willem de Kooning stops painting. (DK627)

His art assistants at the time, Robert Chapman and Antoinette Gay, stopped working for him. (DK627)

September - October 13, 1990: A mini-retrospective of de Kooning's work - "Willem de Kooning: An Exhibition of Paintings" takes place at the Salander O'Reilly Galleries. (DK628)

The review of the show in the September 7, 1990 issue of The New York Times noted that "By focusing on the importance of line, the exhibition emphasizes the structure in the paintings, which, like the impeccable touch, is essential to de Kooning's sense of scale. The emphasis on line also makes a point of the link between de Kooning and Jackson Pollock and, in the process, warns against seeing these two artists as opposites. The kinds of arguments that took place in the 1950's pitting de Kooning, who was first and foremost a painter, against Pollock, whose painting led succeeding generations beyond painting, are still going on. The show is a reminder that de Kooning has not been an either-or artist. He is as comfortable with color as he is with line."

December 1990 - January 19, 1991: "De Kooning/Dubuffet: The Women" at the Pace Gallery. (DK628)

A review of the show by Michael Brenson appeared in the December 7, 1990 issue of the New York Times, noting that "De Kooning/Dubuffet: The Women" is an example of how some of the best New York City galleries are making major museums seem ponderous and predictable. If a museum would ever organize an exhibition on the startling, creepy and sometimes painful images of women painted by Willem de Kooning and Jean Dubuffet in the aftermath of World War II, it might be more comprehensive and scholarly than this one, at the Pace Gallery, but it would probably not be as unpretentious and intimate."

1991

1991: Robert Motherwell retrospective exhibition in Mexico.

After opening at the Museum Rufino Tamayo in Mexico City the retrospective traveled to the Museum de Monterey in Mexico and then the Fort Worth Art Museum in Texas. (HM)

July 16, 1991: Robert Motherwell dies.

See Grace Glueck, "Robert Motherwell, Master of Abstract, Dies," The New York Times, July 18, 1991 and Grace Glueck, "Motherwell Estate is Estimated to Be $25 Million," The New York Times, July 29, 1991)

Motherwell was 76 years old when he died of a stroke after suffering for years from a heart condition. Just hours before he died Motherwell had signed his Will at a Provincetown bank. His estate was estimated to be more than $25 million and to include more than 1,000 works of art, excluding his prints.

The bulk of the estate was left to the Dedalus Foundation, a not-for-profit entity set up by Motherwell. Chairman for the Foundation was Motherwell's wife who was also one of the two executors of his will. The other executor, political science professor Richard Rubin, was the president of the Foundation. Other Dedalus Foundation officers included Jack Flam, Chicago art dealer (and Provincetown neighbour) Lynn Kearney and John Elderfield, the director of the drawings department at The Museum of Modern Art.

A memorial service for Robert Motherwell was held on July 20, 1991 on the beach outside his home in Provincetown. Speakers included the poet Stanley Kunitz who read one of Motherwell's favourite poems - William Butler Yeats' Sailing to Byzantium:

That is no country for old men. The young

In one another's arms, birds in the trees

- Those dying generations - at their song,

The salmon-falls, the mackerel-crowded seas,

Fish, flesh, or fowl commend all summer long

Whatever is begotten, born, and dies.

Caught in that sensual music all neglect

Monuments of unaging intellect.

(First stanza of Sailing to Byzantium)

1993

October 21, 1993: "Willem de Kooning from the Hirshhorn Museum Collection" opens at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden. (DK699)

March 1, 1993: Charles Egan dies at the age of 81.

Art dealer Charles Egan died of pneumonia at the Lennox Hill Hospital in New York. He had given de Kooning his first solo show in April 1948. (The New York Times Obituary, March 18, 1993)

1993: De Kooning's final assistant, Jennifer McLaughlin leaves. (DK627)

1994

May - September 5, 1994: "Willem de Kooning: Paintings" at the National Gallery of Art in Washington. (DK699)

An article by David Cateforis that appeared in the Winter 1994 issue of Art Journal described both the 1994 exhibit at the National Gallery and the Hirshhorn exhibit which opened in late 1993:

After a career that spanned almost six decades, de Kooning, reportedly suffering from Alzheimer's disease, stopped painting around 1990. Thus, the ninetieth anniversary of his birth offered the perfect opportunity to review and assess his life's work in a full-scale retrospective. Neither the Hirshhorn nor the National Gallery was able to take advantage of this opportunity, however. The National Gallery is prevented by its charter from presenting retrospectives of living artists... [and] opted to focus exclusively on de Kooning's paintings of the period 1938-86, excluding his drawings, sculptures, and prints, his earliest abstract canvases, and his very last paintings, executed after 1986. Hirshhorn curator Judith Zilczer drew her show exclusively from the Hirshhorn's own collection of de Kooning's paintings, sculptures, drawings, and prints... [and] the show ultimately revealed less about de Kooning's personal artistic development than it did about Hirshhorn's particular taste in de Kooning... The National Gallery's de Kooning exhibition, which included three pictures from the Hirshhorn (Woman, Two Women in the Country and Woman, Sag Harbor) and seventy-three from other public and private collections, offered the most complete and well-chosen survey of de Kooning's paintings since his first major retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art in 1969.

When the National Gallery show traveled to the Metropolitan Museum of Art (October 11, 1994 - January 8, 1995), the reviewer for The New York Times (Holland Cotter) wrote: "His [de Kooning's] progress was not the leap from height to height that the Metropolitan's show suggests; certain aspects of his output -- the 60's nudes, among them -- will continue to hang fire critically until the fabric of his career has been more thoroughly explored. But at a time when art is hard put to maintain a belief in itself and promising careers tend to fizzle out fast, his very consistency, not to mention his brilliance, is cause for celebration. It is for such celebration that the Metropolitan's imperfect but handsome show is surely intended."

After the Metropolitan Museum of Modern Art the show traveled to the Tate Gallery in London (Feb. 16 to May 7, 1995).

1996: The Academie van Beeldende Kunsten en Technische Wetenschappen, where de Kooning studied as a young man in Rotterdam, officially changes its name to The Willem de Kooning Academy. (DK628)

1997

March 19, 1997: Willem de Kooning dies.

Willem de Kooning studying a door painting - Woman, 1966

(Photo:

Dan Budnik)

De Kooning was 92 at the time of his death. He had outlived most of his artist friends from the early days of Abstract Expressionism. He had suffered through the suicides of his close friends, Arshile Gorky and Mark Rothko and had never been told of Elaine's death from cancer in 1989 or his art dealer's death from AIDS in 1987. His funeral took place the Saturday after his death at Saint Luke's Episcopal Church in East Hampton. About 300 people attended. Guests included his ex-lovers Ruth Kligman, Susan Brockman, Molly Barnes and Emilie Kilgore but the only guest to speak at the funeral was his daughter Lisa. (DK629-30) A reception followed in de Kooning's studio after the funeral and he was buried in the Green River Cemetery - the same cemetery that contained the graves of Stuart Davis, Jackson Pollock, and Frank O'Hara.

From De Kooning: An American Master by Mark Stevens and Annalyn Swan:

Around 1992 and into 1993, he became more withdrawn and no longer recognized Mimi Kilgore. Unable to use the staircase, he lived downstairs and, increasingly, was given liquids. According to Joan Ward, he was 'warm and fed. That's about it.' In the end, de Kooning's heart, which had consistently worried him over the years, sometimes sending him to the hospital with palpitations, never faltered. And his legs retained their muscle tone after years of biking. But he barely survived an inflamed hernia during the winter of 1994-95, which sent his temperature spiking upward. 'When Bill came back from the hospital, he was curled up with his head on one side,' said Ward. Somehow, the will to live continued. His color improved, and he was taken off intravenous antibiotics. But for the next two years, as de Kooning sank farther into the final breakdown of dementia, the antibiotics failed to clear up pneumonia in his lungs, which eventually presaged a body-wide failure. De Kooning's temperature would sporadically soar; he would begin to thrash around, his nurses would rush him to the hospital. 'The last time was like lightning,' said Ward. 'It's like a series of chain strokes.' On March 19, 1997, at the studio, his breathing stopped, and did not start again. (DK629)

2002

November 23, 2002: Roberto Matta dies.

Roberto Antonio Sebastián Matta Echaurren had left New York after Gorky's death in 1948. Although his reputation had suffered as a result of his affair with Gorky's wife days before Gorky committed suicide, Matta was eventually accepted back into the Surrealist fold in 1959 and continued his career abroad. But his personal life was plagued by tragedy. Both of his twin sons died early deaths. John Sebastian fell from his twin brother's window in 1976 after a history of mental illness and his twin brother, the artist Gordon Matta-Clark, died two years later of pancreatic cancer. (RE)

David Ebony [from "Roberto Matta, 1911-2002," Art in America, January 1, 2003]:

Matta, 91, painter who was the youngest member of the prewar Surrealist group in Paris and a key figure in the development of Abstract Expressionism in New York, died on Nov. 23 at a hospital near his home in Tarquinia, Italy, about 70 miles north of Rome. Born Roberto Sebastian Matta Echaurren in Santiago, Chile, of French and Spanish descent, he earned a degree in architecture from the Catholic University of Santiago in 1931. Two years later, Matta sailed to Paris and found work as a draftsman in Le Corbusier's studio, where he stayed until 1937, taking time off periodically to explore Europe. In Spain he met Federico Garcia Lorca and Salvador Dali, who introduced him to Andre Breton. Experimenting with "automatic writing," Matta joined the Surrealist group in Paris in 1937. That year he produced his first drawings; his first oil paintings appeared the following year. Rendered in bright colors, with frenzied lines and brushstrokes, these abstractions, which he referred to as "inscapes" or "psychic morphologies," suggest a cosmic space with apocalyptic overtones.

... At the urging of Marcel Duchamp, Matta, like many other European artists, migrated to New York in 1939... Returning to Europe in 1948, he first settled in Rome, but in 1955 relocated to Paris, where he lived until 1969, eventually becoming a French citizen. After the mid-'60s, he divided his time between Italy, France and England. He fathered six children, including twins, the artists Sebastian and Gordon Matta-Clark, born in 1943 (both died in the late 1970s). Matta's widow, Germana Ferrara Matta, is currently preparing his catalogue raisonné. Gordon Matta-Clark's widow, Jane Crawford, is completing work on a documentary film about Matta; titled Matta: The Eye of a Surrealist; it is scheduled for release later this year.

Long associated with leftist politics, Matta presided over the cultural congress in Havana in 1966, and from 1970 to '72 traveled in Chile and Peru at the invitation of Chile's President Allende. Matta was honored with a number of retrospectives, beginning with a 1955 show at New York's Museum of Modern Art. Major surveys also appeared in Stockholm (1958), Bologna (1963), Mexico City (1964), Berlin (1970), Paris (1971), London (1977) and Tokyo (1986). In 1995 he won Japan's Praemium Imperiale Award for lifetime achievement in the arts. His most recent U.S. survey, "Matta in America," focused on his 1940s works; it debuted in 2001 at Los Angeles's Museum of Contemporary Art, and traveled in 2002 to the Miami Art Museum and the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago."

2004

March 12, 2004: Milton Resnick commits suicide.

Resnick was one of the founders of The Club and was particularly close to Willem and Elaine de Kooning. He had been in a relationship with Elaine during the 1930s before she became involved with Bill. (DK)

Roberta Smith ["Milton Resnick, Abstract Expressionist Painter, Dies at 87," The New York Times (March 19, 2004)]:

Milton Resnick, a New York painter known for dour, thickly impastoed near-monochrome canvases, died on March 12 at his home on the Lower East Side of Manhattan. He was 87 and also had a home in Cragsmoor, N.Y.

His wife, the painter Pat Passlof, said Mr. Resnick committed suicide.

... In terms of longevity and dedication to first principles, Mr. Resnick might qualify as the last Abstract Expressionist painter. In terms of timing he had some claim to being among the first. Born in the Ukraine in 1917, he emigrated to New York with his family in 1922 and grew up in Brooklyn. He left home as a teenager when his father forbade him to become an artist.

By 1938 he had rented his first studio, on West 21st Street, and was friendly with artists like Ad Reinhardt, Willem de Kooning, Elaine Fried (who married de Kooning) and Ibram Lassaw. He worked briefly on the W.P.A. arts project, started painting abstractly in the early 1940's and was a founding member of the Club, the Abstract Expressionist forum.

Yet Mr. Resnick was, as he put it, out of the picture. Having spent much of the 1940's serving in the Army during World War II and studying in Paris on the G.I. Bill, he was generally seen as working in de Kooning's shadow until the mid-1950's and therefore relegated to Abstract Expressionism's second generation, which he bitterly resented.

As the 1950's progressed, his contemporaries became prominent, and Pop and Minimalism loomed; he came to feel excluded from the New York art world's past as well as its present. In the introduction to ''Out of the Picture,' Mr. Dorfman poignantly and succinctly sums up Mr. Resnick's predicament: "His most significant achievements took place subsequent to the dissolution of the world that bred him."

2005

April 13, 2005: Philip Pavia dies.

Philip Pavia, a sculptor and one of the founders of The Club, died at the New York University Medical Center from complications following a stroke he suffered two weeks earlier. He was 94 years old. (PN)

The month before his death one of his sculptures went missing. On Wednesday, March 23, 2005, Pavia received a phone call from Andrew Gottesman who owned the Hippodrome, an office building at Avenue of the Americas and 43rd Street. Pavia's four piece bronze sculpture The Ides of March had been installed there since 1988. The artist was informed that three of the four pieces were missing. The work had been stored in a storage area at the building since the summer, pending its move to Hofstra University on Long Island. It had been insured for $65,000. The statue had originally been commissioned in 1962 for the porte-cochere entrance of New York Hilton on Avenue of the Americas at 53rd Street where it was displayed prior to the move to the Hippodrome building. The four pieces ranged in height from 6 to 10 feet and weighed about 3,000 pounds in total. The three missing pieces weighed about 600 pounds each. Although the room was protected by a gate and alarm system the alarm system had been disabled during building renovations. On Thursday, the day after the three pieces went missing, a man, calling himself a "scrap collector" showed up at the building to collect the remaining piece but was interrupted by the building superintendent who called the police. The pieces were eventually returned by a scrap metal dealer after he learned that the pieces were stolen. He had apparently been sold the items as scrap metal from someone who had been picking up scrap metal from a nearby construction site but had not been authorized to remove the sculpture. (PS)

When interviewed about the sculpture by a reporter for The New York Times just days before the missing pieces were found and less than a month before his death, Pavia commented, "Naturally I am saddened and shocked that a piece of beauty and a piece of New York has disappeared, but I am an active artist and I am going back to work." (PQ)

From The Times (London) obituary:

At a party in Manhattan on New Year’s Eve 1949, a man was heard to exclaim to his fellow artists in the room that the first half of the century had belonged to Paris, but the second would be claimed by New York. The author of that declaration of independence — part rallying cry, part prophecy fulfilled — was Philip Pavia, whom history is likely to remember as much for his organisational role within the Abstract Expressionist movement as for the sculptures he contributed to it... (PI)

[end.]