Abstract Expressionism 1925 - 1927

by Gary Comenas (2009, Updated 2016)

1925

January 9, 1925: Arshile Gorky is admitted to the National Academy of Design in New York City.

Gorky moved to New York, studying as a day student in a life drawing class at the National Academy taught by the Realist painter Charles Hawthorne. Gorky initially stayed in a rooftop studio lent to him by someone named Sigurd Skon. By September 1926 he was living on West Fiftieth Street and later that year, or early in 1927, he moved to a studio on Sixth Avenue at 57th Street (probably the studio he shared with a friend, a Greek-born art student named Stergis M. Stergis). In 1928, after Stergis told him he was leaving New York, Gorky moved into his own studio on the second floor of 47a Sullivan Street on the corner of Washington Square South. (HH128)

When Gorky registered for the National Academy (located at 109th Street and Cathedral Parkway), he gave his address as 1680 Broadway, his date of birth as April 1902, and his place of birth as Kazan, Russia - a town that the writer Maxim Gorky had lived in during his teenage years. He stayed at the school for only one month, leaving on February 9th. (HH129/BA142)

The address that Gorky gave to the Academy - 1860 Broadway - was actually the address of the New School of Design in New York - the sister school of the Boston New School of Design which he had previously attended. (The school was not related to the New School for Social Research in New York.)

Gorky enrolled in the New School of Design in New York about the same time as he enrolled at the National Academy. When the New School of Design moved to 145 East Fifty-seventh Street in 1926, Gorky was still registered with the school. His tuition at the New School of Design was probably waived as Gorky served as class monitor and, according to Mark Rothko who was in Gorky's class, also taught at the school.

Mark Rothko:

Gorky came down from Boston with Mr. Connah (the President of the Boston New School of Design). Gorky was the monitor in the class in which I was enrolled... Gorky was head of the class, in charge of it. He taught, as well as saw to it that the students were on good behaviour. And he expected good performance. He was strict. Perhaps I shouldn't say this, but Gorky was overcharged with supervision. (HH130)

Rothko also recalled that when Gorky spoke of his childhood, it was "difficult to tell where reality ended and imagination began... He had a wild, poetic imagination... always expounding about the unique beauties and poetry of the place of his birth." (HH130)

Mark Rothko:

At that time, when I first met him, he liked Monticelli. He also made copies of Franz Hals in the Metropolitan Museum. This is not to imply that Monticelli and Hals were necessarily his favourite artists. Not at all. As a teacher, he had to make do with what original works of art were available for viewing by students. It was part of his job to lecture to us and expound on the techniques used by the artists hanging in the Metropolitan... (BA142)

July 1, 1925: Franz Kline moves in with his mother and step-father.

Kline had been attending the free boarding school, Girard College, in Philadelphia since 1919 - two years after his father's suicide. His mother, who had remarried in 1920, had sent his school a letter on June 26, 1925 informing them of her intention to withdraw Kline from the school who was not doing well academically. Once he joined his family in Lehighton, Pennsylvania, he lived at home for more than a year, working at the Lehighton dairy before enrolling in the local public school. (FK175)

Autumn 1925: Arshile Gorky attends exhibition of the Blue Four at the Daniel Gallery. (BA147)

The Blue Four were Lyonel Feininger, Paul Klee, Vasily [Wassily] Kandinsky and Alexei von Jawlensky. Arshile Gorky attended the exhibition. (BA147)

Autumn 1925: Clyfford Still studies at the Art Students' League - for forty five minutes.

Still visited New York for three months. In addition to signing up for a class at the Art Students' League and then leaving after forty-five minutes, he also visited the Metropolitan Museum where he was repelled by the use of paintings to "glorify popes and kings or decorate the walls of rich men." (RO225)

October 1925: Arshile Gorky attends the Grand Central School of Art in New York.

The Grand Central School of Art in New York had opened on the seventh floor above the Grand Central Terminal (accessed by taking the elevator at track 29) in 1924. The director of the school was the American Impressionist, Edmund Graecen. One of Gorky's first instructors there was the Russian-born Realist artist, Nicolai Ivanovich Fechin. (HH130)

Stergis M. Stergis:

We [Gorky and Stergis] used to study together at the Grand Central Art School under Nikolai Fechin, a great Russian painter, day and night, through the years 1925 to 1928. Gorky thought Fechin was one of the greatest painters. He had a wonderful technique. I have a portrait here [by Gorky]. You'd think it was painted by Fechin. (BA147)

According to Stergis, Gorky lived with him for 1 1/2 years - presumably at the studio mentioned earlier on Sixth Avenue at 57th Street.

Stergis M. Stergis:

Books I read on him [Gorky] were real artificial. Not the real Gorky. Gorky was such a character. I really want to see something right on him. I knew Gorky better than anyone. He ate with me and slept with me and lived with me for one year and a half. We had piles of paintings. A few days we went down and burned a lot of them in the incinerator because we got tired of all those canvases. Mine I didn't care about, but probably, we burned a fortune in Gorky's - his early paintings. (BA149)

Stergis also recalled that Gorky attempted to earn some money by doing commissioned portraits which he thought had been arranged through Knoedler Galleries. Ethel Cooke, the instructor from Boston's New School of Design, also recalled that Gorky did commissioned portraits but thought that they had been arranged through the Ferragil Gallery on 57th Street in New York. (BA147)

Stergis M. Stergis:

Knoedler Galleries, I think it was, commissioned him to paint five portraits of different women, the cheapest one, I think, was $1,500 or $2,000 to $3,000. At the time they gave him a very nice studio. he painted one of the women. The most beautiful portrait! She had a black velvet dress with green sash thrown over, from one shoulder down. Very beautiful!

At the unveiling, they had a lot of family friends. The husband remarked to Gorky, taking him aside, "Would you mind to tone down the lips?"

He had a beautiful bright spot on the lips. Gorky threw up his hands. He started swearing in Russian. He pulled the canvas down. And of course, the result? They had advanced a thousand dollars, which he had spent for canvases and so on. He was eating for a change. That money was gone. He never got the balance of it. He had no place to go. I said, "Arshile come to my place, until you find another place."

He moved in with me. He only finished one painting, and that was the unhappy ending of it. He didn't do the rest. The gallery didn't want nothing to do with him. (BA148)

Stergis also recalled that Gorky would visit the Metropolitan Museum to paint the Old Masters.

Stergis M. Stergis:

I have a painting he did at the Metropolitan Museum of a Rodin statue, The Poet and the Model... He set up his easel [and at the end of the day] had to pick up his belongings and take them to the locker at four o'clock. Well, he forgot the time. The guards got annoyed. "Either stop at the right time and pick up all those things or we won't let you in!" So, he goes and buys himself an alarm clock. He was quite a character. Tall, long hair... He put paint on canvas and walked back again. People were attracted and stood around watching him instead of going to the gallery. There was quite a crowd over there, every day, when he was painting. Finally, at four o'clock the alarm clock would go off! And then, he'd take the stuff to store. (BA153)

By September 1926 Gorky was also teaching at the Grand Central School of Art. An article in the September 15, 1926 issue (see below) of the New York Evening Post announced his appointment. One of his students, Arthur Revington, recalled that Gorky was an early art star at the school - students were "immediately divided into two camps: for Gorky and against Gorky. He was a very exciting teacher. You knew immediately that he was a good artist. No question about it... I had at that time never heard of Cézanne. When I went there in 1927, Gorky was already speaking about Cézanne." (BA151) Another student, Nathaniel Bijur, recalled Gorky skillfully finishing a painting, Tulips, in "just two hours, as a classroom demonstration." Bijur bought the painting for $100 in 1926. (BA152)

October 1925: Mark Rothko enrolls again at the Art Students League. (RO56)

Rothko took Max Weber's still-life class for six of the next seven months at a cost of $13 per month. (RO60) In New York a distant relative, Mrs. Goreff, allowed him to stay in a spare room in her home at 19 West 102nd Street. She later recalled that he "played a lot of Bach on our phonograph and painted." (RO56) During this period, Rothko sketched charcoal and pencil drawings of Central Park, Harlem and the El.

c. 1925: Arshile Gorky's sister, Vartoosh, and her husband, Moorad, join the Communist Party. (BA144)

Vartoosh was still living with her sister Akabi at the time. When a friend of Akabi's asked "Why do you let those people hold Commie meetings in your house?" Akabi answered "What business is it of anybody's? My sister does as she pleases in my house!" (BA144) In 1927 Gorky addressed a meeting that Vartoosh and Moorad took him to - a fund raising fair of the Harractimagan - referred to by Gorky biographer, Nouritza Matossian as "a thinly veiled Communist organization sending aid to Armenians under the Soviet regime." (BA155)

1926

1926: The Motherwells move to California.

Robert Motherwell and his family lived in Southern California before moving to Northern California. While in Southern California, Motherwell went to the Otis Art Institute on a scholarship.

Robert Motherwell:

We were then living in Beverly Hills and the Los Angeles public school system awarded a scholarship to a boy and a girl from all the public schools every year. I won it as a boy. But my father had a very negative reaction, and my mother used to have to drive me in a car, you know, miles. Finally they made it so disagreeable that I gave it up. I was about - I don't know how old - ten, eleven, twelve, something like that. And I wanted to paint the nudes. They wouldn't let me in the nude class. They made me paint still lifes. I didn't want to do that. So I finally gave up, too. (SR)

1926 - 1929: Adolph Gottlieb studies at the Art Students' League and the Educational Alliance.

Gottlieb took evening classes at the League with Richard Lahey and a sketch class at the Educational Alliance, a community center on East Broadway where he came into contact with Chaim Gross, Barnett Newman, Mark Rothko, Louis Schanker, Moses and Raphael Soyer and Ben Shahn. (AG14)

1926: Jackson Pollock's brother, Charles, moves to New York.

Charles Pollock enrolled in the Art Students League, studying under Thomas Hart Benton. (PP316)

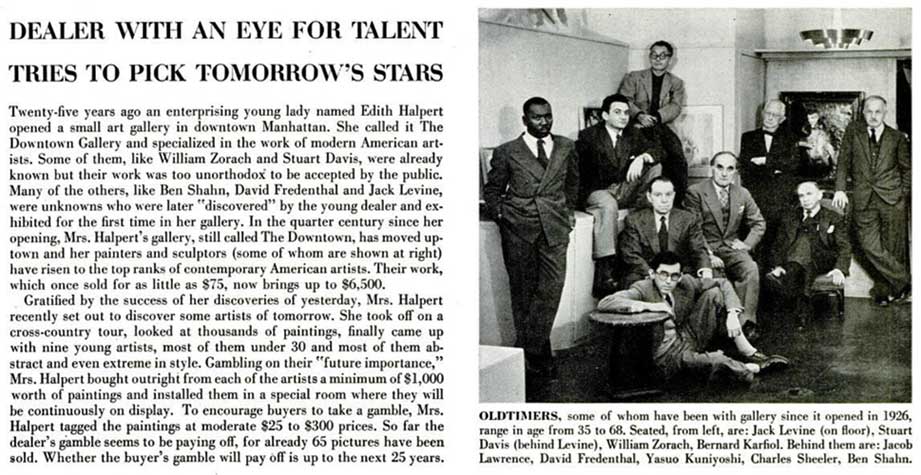

1926: The Downtown Gallery opens. (BA194)

The Gallery had opened in November 1926 as "Our Gallery" at 113 West 13th Street. The following year the name was changed to the Downtown Gallery at the suggestion of William Zorah.

Arshile Gorky was one of the artists who exhibited there. He may have been introduced to the gallery owner by Stuart Davis who also showed there. During 1931 the Downtown Gallery received seven works by Gorky, priced $100 to $450. (The artist's name was spelled "Archele Gorki" in the gallery's records. Most of Gorky's works from this period were unsigned.) (BA195/546)

In April 1932 the gallery showed Lithuanian-born artist Ben Shahn's controversial Sacco and Vanzetti paintings.

In March 1952 Life magazine ran a two page article on the gallery:

From "New Crop of Painting Protégés," Life magazine, Vol. 32, No. 11, March 17, 1952

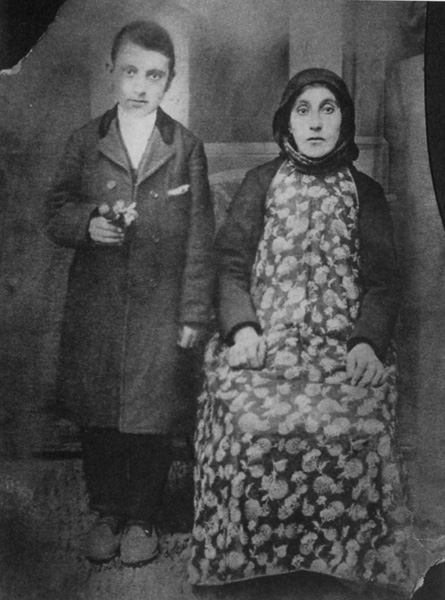

1926: Arshile Gorky begins painting The Artist and His Mother.

Photograph of Arshile Gorky and his mother, Van city, Turkish Armenia, 1912

The Artist and His Mother (1926-1936) (Oil on Canvas, 60 x 50 inches), Whitney Museum of American Art

The Artist and His Mother (1926 - c. 1942) (Oil on Canvas, 60 x 50 inches) National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Two versions of the painting exist - one at the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C. (finished in c. 1942) and one at the Whitney Museum of Modern Art (finished in 1936). The one in Washington has warm, almost terra cotta colours whereas the Whitney version has pale golds, ochre, green. (BA214) The colours are more solid in the Whitney version, with more abstract brushstrokes in the later version.

Saul Schary:

This picture took a hell of a long time. He'd let it dry good and hard. Then he'd take it into the bathroom and he'd scrape the paint down with a razor over the surface, very carefully until it got as smooth as if it were painted on ivory. you look at that picture and you won't be able to tell how he did it because there are no brushstrokes. Then he'd go back and paint it again, all very fine and done with very soft camel-haired brushes. he scraped it and he scraped it and he scraped it. Then he'd hold it over the bathtub and wipe off with a damp rag all the excess dust and paint that he'd scraped off. That's how he got that wonderful surface. It's the only painting he ever did that way. (BA217)

Gorky's sister, Vartoosh, later described what her reaction was when she saw the painting for the first time. Gorky sat her down in his studio, saying "Vartoosh dear, here is Mother. I am going to leave you alone with her." Vartoosh recalled, "Oh, I was so shocked! Mother was alive in the room with me. I told her everything and I wept and wept." (BA218)

May 1926: The first issue of The New Masses is published.

The monthly publication was started by the former editors of The Liberator and the The Masses. It's goal was to "regularly interpret the activities of workers, farmers, strikers etc..." noting that it "must not be afraid of slang, moving picture[s], radio, vaudeville, strikes, machinery or any other raw American facts." It promised that "at least half of the pages will consist of pictures. These will be cartoons of our current political and social events, drawings of American life and also, though not ever predominantly, pictures that have no 'journalistic' value but are based on the emotion of art." Hugo Gellert and John Sloan served as art editors for the magazine. Drawings often featured American workers interacting with machinery such as construction workers and pneumatic-drill operators. Contributors included David Burliuk, Gan Kolski, Louis Lozowick, Jan Matulka, Morris Pass, Ribak, Boardman Robinson and William Siegel. Abstract designs often appeared on the cover or as illustrations including cubist cityscapes by Lozowick and Matulka, futuristic designs by Abraham Walkowitz and geometric designs by Lozowick. (VH) From 1936 to 1946, many of the cartoons in the magazine were by Ad Reinhardt.

Michael Corris [from the Introduction to Ad Reinhardt (Reaktion Books, 2008)

My sustained interest in Reinhardt began with the unexpected discovery of a clutch of cartoons and illustrations drawn by the artist for New Masses, an important left-wing journal of politics and culture of the 1930s and early 1940s. By the end of what turned out to be merely the first phase of an extended project of research on the artist, I had uncovered more than 400 examples of cartoons and illustrations, many of which were signed using a variety of pseudonyms and some of which were drawn in collaboration with another artist, Abe Ajay. These works were produced over the course of a decade - 1936 to 1946 - during the most important formative period of Reinhardt's career. It was the time when Reinhardt studied art in earnest with painters such as Francis Criss and Carl Holty, made the acquaintance of Stuart Davis, Harry Holtzman and Peggy Guggenheim, became involved with the American Abstract Artists group and mounted his first solo exhibitions in New York. (RT11)

The magazine changed from a liberal publication sympathetic to workers to a more radical magazine produced for and by the workers in June 1928 when Michael Gold became editor in chief and Hugo Gellert became art editor. Gellert was an avowed communist who expressed the belief that "proletarian realism" was "never pointless" as "it portrays the life of workers.... with a clear revolutionary point.' (VH)

In November 1930, The New Masses became the official journal of the International Union of Revolutionary Writers (IURW) and the International Bureau of Revolutionary Arts (IBRA) at the Kharkov conference. A conference statement, "To All Revolutionary Artists of the World" proclaimed that artists must fight "for revolutionary content and form in art, intelligible to the broad working masses and based on the class struggle; for the synthesis of class content and new form in revolutionary art." At the end of 1931, however, The New Masses was criticized by the IURW for its illustrations which, they felt, showed insufficient militancy and a preoccupation with aesthetic innovation and formalism - the example given was Lozowick's drawings of factories and construction sites in which the worker was secondary to the design elements of the composition. (VH)

As the Great Depression progressed, The New Masses became even more radicalised, adopting a weekly format in 1933. Illustrations were increasingly replaced by photographs of actual events. It ceased publication in 1948. (VH)

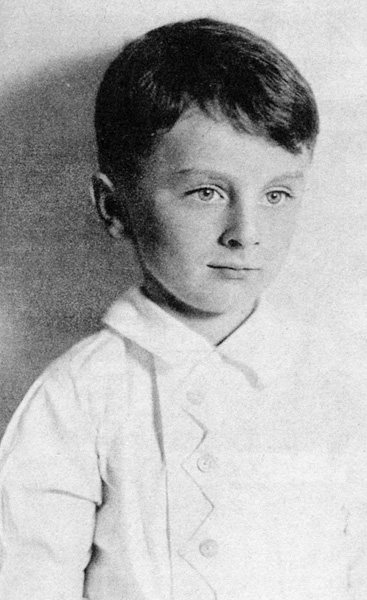

June 27, 1926: Frank O'Hara is born in Baltimore.

Frank O'Hara, 1931

Frank O'Hara's poems often make reference to Abstract Expressionists who he knew and socialized with. (His lovers included the New York School artist, Larry Rivers.) Frank arrived in New York in 1951 and shortly thereafter began working at the front desk at The Museum of Modern Art where, in 1960, he became the Assistant Curator of Painting and Sculpture Exhibitions. During the 1950s he could often been seen at the Cedar Street Tavern. In 1959 a monograph on Jackson Pollock by O'Hara was published as part of The Great American Artists Series.

O'Hara died on July 25, 1966 after being hit by a beach buggy on Fire Island during the early morning hours.

John Gruen [writer and composer]:

Self-destructive during the last years of his life, Frank still seemed indestructible. His death came as an enormous shock to all of us gathered under the great elms at The Springs cemetery. Larry Rivers spoke, giving a description of Frank in his hospital bed two or three days before he died. It was a hair-raising evocation of broken bones, blue skin and horrible wounds. During the speech Frank's sister fainted and had to be carried to her car. I don't know why Larry chose to be so insistently graphic, but perhaps he wanted to get as close as possible to Frank during those last days, and he wanted to give us a side of Frank that none of us had ever seen. It was an odd, repulsively detailed talk and many of us later upbraided Larry for it...

After the funeral a number of Frank's closest friends went to Patsy Southgate's nearby house and drank a great deal. A year later Bill Berkson compiled a book that honoured Frank's memory. Commissioned and published by the Museum of Modern Art, it is titled In Memory of My Feelings. Bill asked thirty artists to illustrate a selection of Frank's poems. The list of names represents the people Frank O'Hara was close to during his life, and who were equally affected by him: Nell Blaine...Joe Brainard...Allan D'Arcangelo, Elaine de Kooning, Willem de Kooning...Helen Frankenthaler... Jasper Johns.... Robert Motherwell... Barnett Newman... Robert Rauschenberg, Larry Rivers and my wife, Jane Wilson. (JG153-4)

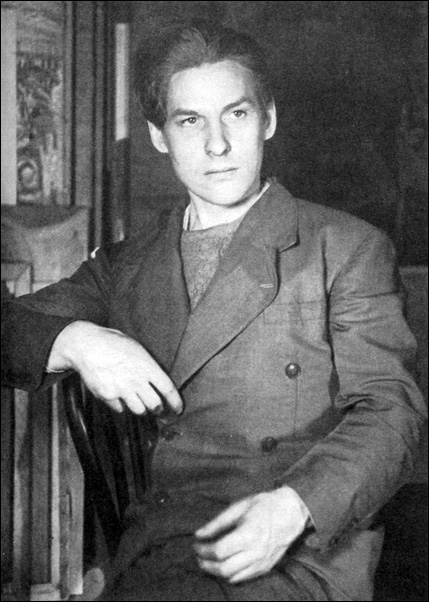

July 30, 1926: Willem De Kooning arrives in the United States.

Willem de Kooning in the late 1930s

(Photo: Ellen Auerbach)

See Willem de Kooning leaves Holland.

Willem de Kooning had left Holland on July 19, 1926 as a stowaway on the British ship S.S. Shelley bound for Virginia. It arrived at its final destination, Newport News port in Virginia on July 30, 1926. De Kooning's first impression of America was disappointing. There were no gleaming skyscrapers or Statue of Liberty at the Virginia port. To de Kooning America looked like "a sort of Holland, lowlands, just like back home." (DK61) However, arriving in Virginia rather than at Ellis Island worked in de Kooning's favour. The Immigration Act of 1924 limited the amount of immigrants allowed into the U.S. and if de Kooning had arrived at Ellis Island he would probably have been deported. Once arriving in the U.S. de Kooning and Leo Cohan (who had arranged for de Kooning to stow away), made their way to New York via boat and train, settling in Hoboken, New Jersey at the Holland Seaman's Home. (DK62)

De Kooning would later describe his reaction when, after arriving in Hoboken, he wandered into the Hoboken train and ferry terminal:

Willem de Kooning:

It was early in the morning and a thousand guys in hats ran in. You know, commuters. A guy at the diner counter had all these coffee cups lined up. He had a big coffee pot, like a barrel, and he poured without lifting it, one end of the counter to the other in cups... I thought, What a great country! I always remembered that guy with the coffee when my Communist friends in Greenwich Village used to say this is a lousy country. I told them they were nuts. (IS51)

"Three days later I was a housepainter," de Kooning later said, "and got nine dollars a day, a nice salary for that time." (LO) After living in Hoboken for approximately a year, de Kooning moved to Manhattan after finding a job at a firm of designers, the Eastman Brothers. The firm was similar to Gidding and Zonen, who de Kooning had worked for in Holland, but whereas Gidding and Zonen were known for the quality of their design, the Eastman Brothers, according to one person who worked there in the 1920s, were modern imitators rather than old school craftsmen - "Instead of making real stained glass, for example, they made fake glass... Everything was theatrical, for show. They weren't respectable... After we finished a glass window... a man would come and do stippling to make it look like it was old glass." (DK69-70)

Autumn 1926: Jackson Pollock enrolls in Manual Training School, Riverside. (PP316)

According to the Jackson Pollock chronology published by The Museum of Modern Art in Jackson Pollock, Jackson enrolled in the "Manual Training School" in Riverside, California after graduating from Grant Elementary School and before enrolling at Riverside High School in the autumn of 1927. The Manual Training School in Riverside should not be confused with Manual Arts High School which Jackson attended beginning in September 11, 1928 after dropping out of Riverside High School in March 1928.

September 1926: Franz Kline enrolls in Lehighton Junior High.

Kline received an A in his art course taught by Miss Hazel Stauffer. (FK174)

September 15, 1926: Arshile Gorky appears in the New York Evening Post. (BA150)

The New York Evening Post featured an article about Gorky being appointed as an instructor at the Grand Central School of Art. The article was titled "Fetish of Antique Stifles Art Here, Says Gorky Kin." The article referred to Gorky as "a member of one of Russia's greatest artist families, for he is a cousin of the famous writer, Maxim Gorky," adding "But Arshele Gorky's heart and soul are still his own." (BA150) Given that Gorky was not the cousin of Maxim Gorky (although he claimed to be such) and had never met him or his family members, it's not surprising that his "heart and soul" remained his own.

The article included Gorky's comments about art ("Cézanne is the greatest artist that has lived") and American art in particular:

Arshile Gorky:

Your Twachtman painted a waterfall in any country, as Whistler's mother was anyone's mother. He caught the universal idea of art. Art is always universal. Art is not in New York; art is in you. Atmosphere is not something New York has, it is also in you. (BA150)

November 18, 1926: “An International Exhibition of Modern Art Assembled by the Société Anonyme" at the Brooklyn Museum opens.

A list of Société Anonyme exhibitions in the 1920s can be found here.

Organized by Katherine Dreier, with help from Marcel Duchamp, Léger, Kadinsky, Campendonk, Kurt and Helma Schwitters, Alfred Stieglitz and Anton Giulio Bragaglia, the exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum attracted more than 52,000 visitors and featured 308 works by 106 artists from at least 19 different countries, traveling to three other cities after finishing in Brooklyn.

(JAX)

Four galleries in the exhibition were made up to look like rooms in a house in order to illustrate how modern art could be incorporated into the modern home. A television room designed in conjunction with Frederick Kiesler, who would later design Peggy Guggenheim's Art of This Century gallery, showed how any home could be a virtual museum with masterpieces (on slides) available at the "turn of a knob." Eighteen lectures were presented during the course of the exhibition - fourteen by Dreier herself who also had two of her own paintings in the show.

Stuart Davis was represented by Still LIfe with Super Table (1925) - a work which may have been inspired by a 1919 painting by Picasso published in The Arts magazine in the United States in 1925. Davis had written to Dreier on September 25, 1926, about two months before the show opened, telling her that "Burliuk saw my work and said I should be in the show. I would like very much to be a member of the Societe and will do anything you may suggest to make it possible..."

(JAX/)

Ruth L. Bohan suggested in "The Societe Anonyme's Brooklyn Exhibition: Katherine Dreier and Modernism in America" (1982) that Davis' viewing of the work of Russian artist and graphic designer, El Lissitzky, in the exhibition was the catalyst for his Egg Beater series. El Lissitzky had seven paintings in the exhibition - LN31, Proun 2PR, Proun 99, el Proun 97, W.B. Proun 98, Proun 100 and Proun 95 although only Proun 99 was reproduced in the exhibition catalogue. In a letter to Katherine Drier, dated April 15, 1927, El Lissitzky was the only artist that Davis mentioned by name, writing "Looking through the catalogue has been a very stimulating experience. I have gotten more from the catalogue than from the exhibition itself owing to the understanding that comes with familiarity. It would interest me very much to see more reproductions of the constructionist school, Lissitzky, etc..." (JAX)

1927

1927 - 1928: Franz Kline's freshman year at Lehighton High School in Pennsylvania.

Franz Kline's highest grades during his freshman year was a B in industrial arts and an A in manual training. He drew outside of school, often at home on large drawing pads. On St. Patrick's Day he painted a green mustache on a bust of Benjamin Franklin in the school library. When asked to explain his action, he commented, "But he looked so dead!" In the summer he went to the Citizen's Military Training Camp in Fort Monroe, Virginia. (FK175)

1927-1928: Stuart Davis paints his Egg Beater series.

Egg Beater No. 1 (1927) (Oil on canvas) (29 1/8 x 36 in.) (Whitney Museum of American Art)

Stuart Davis:

You may say that everything I have done since has been based on that eggbeater idea. (JAX)

Some art writers have drawn an analogy between Picasso's work of the late 1920s and the series, however Karen Wilken notes in an essay entitled "Becoming a Modern Artist: The 1920's" in the 1991 exhibition catalogue Stuart Davis: An American Painter (1991) that "The similarity between the Egg Beaters and Picasso's works of the late 1920's has often been noted. Davis, like many of his contemporaries, paid close attention to Picasso, but knew his work chiefly from reproductions. Picasso's pictures of this type were not shown in New York until Davis was well into the Egg Beater series." (JAX)

1927: The Gallatin Gallery of Living Art opens at Washington Square in Greenwich Village, New York.

Gorky often visited the gallery where he saw work by Jean (Hans) Arp, Robert Delaunay, Joan Miró, Piet Mondrian, Picasso and Braque. (BA179)

1927: Barnett Newman graduates from City College of New York.

After Barnett Newman graduated from City College his father suggested that he join the family clothing manufacturing business at 37 East Broadway as a full partner (along with his brother George) for a few years. If he still wanted to become an artist after that he would at least have saved up some money to support himself with. Adolph Gottlieb encouraged him to take up his father's offer. Newman took the position but in 1929 the business suffered as a result of the Great Depression. Although Barnett urged his father to declare bankruptcy, his father decided to try and salvage his business. Newman's brother George left the business and became an architectural draftsman at Barnett's urging. Newman's father finally retired in 1937 after having a heart attack and Barnett then liquidated the business. (MH/TH13)

June - July 1927: Jackson Pollock works at the Grand Canyon.

In the summer of 1927, when Jackson was fifteen years old, he and his brother Sande traveled to the Grand Canyon in a used Model T which they purchased for twelve dollars. During the summer they joined their father, LeRoy, on a surveying team working on the roads on the canyon's northern edge during the summer. (JP35) According to the chronology published by The Museum of Modern Art in Jackson Pollock,

Jackson had his "first alcoholic drink" during this period. The same chronology notes that by autumn of the same year, Jackson "although only fifteen" was "already drinking heavily." (PP316)

August 23, 1927: Sacco and Vanzetti are executed. (PB)

August 27, 1927 - Late December 1927: Mark Rothko illustrates The Graphic Bible. (RO66)

The Graphic Bible was the idea of Rabbi turned author Lewis Browne who had, by 1927, authored two other books - a history of the Jews titled Stranger than Fiction (1925) and a book about world religions, The Believing Religion (1926). The Believing Religion was particularly popular. It sold about 100,000 copies and won an honourable mention for its illustrations from the American Institute of Graphic Arts. Rothko had first met Browne, who was the cousin of one of Rothko's friends, in 1921. In 1927, when both were living in New York, Rothko contacted Browne looking for work and Browne recommended him to four advertising agencies who failed to hire Rothko because of his "inexperience" and "inability." He also recommended Rothko to Lloyd Goodrich, then the associate editor of Arts Magazine, who also failed to hire Rothko. (Goodrich would later become director of the Whitney Museum which Rothko once referred to as a "junk shop." (See December 20, 1952))

In August Lewis Browne signed a contract for The Graphic Bible which allocated $500 for an assistant to help with the illustrations. The book consisted of re-creations of events in the Bible through text and illustrated maps, aimed mostly at younger readers. Browne hired Rothko to do the illustrations. Over a period of four months, Rothko worked on the illustrations seven days a week, four or five hours a day, completing his work in late December. (RO67) Browne was apparently so pleased with Rothko's work that he promised him a credit on the book and a share of the royalties. When Browne did neither, Rothko sued. Rothko lost the suit in early 1929. The New York Times covered the trial and quoted Browne referring to Rothko's work as "monkey-doodles and jiggles" - a term actually used by Browne's lawyer. (Browne had actually called Rothko's illustrations "little wiggles and jiggles and lines.") (RO577)

Autumn 1927: Jackson Pollock enrolls at Riverside High School.

Jackson was expelled from the ROTC program at the school after he punched a student officer while drunk. (PP316) The student officer had criticized him over the condition of his uniform and Jackson had grabbed him, calling him a "Goddamn son of a bitch" in front of the rest of the platoon. (JP34)

December 11, 1927: Jackson Pollock's father apologises to his son.

In a letter to Jackson Pollock, his father, who had left his wife and children on October 20, 1920, wrote "I am sorry that I am not in a position to do more for all you boys and I sometimes feel that my life has been a failure - but in this life we can't undo the things that are past." (JP35)