Warholstars Condensed... sort of

page twelve

One year prior to the making of The Chelsea Girls a new person had joined the Factory who would go on to direct some of the most commercially successful films produced by Andy Warhol. It was:

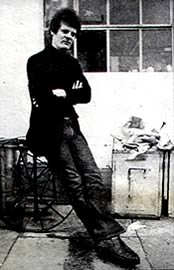

PAUL MORRISSEY

Left: Photo: Annie Leibovitz (1971)

Right: Photographer unknown (c. 2003)

Although Paul Morrissey operated the camera during some of filming of The Chelsea Girls, Warhol actively participated in both the conception and actual shooting of the film. When Ondine slapped Ronna Page, Warhol was behind the camera for at least some of the scene. British artist Mark Lancaster was at the Factory when the scene was shot and remembers that Warhol took an active role during the filming.

"I hung out at the Factory... and one day arrived as they were setting up a scene. I think the filming of The Chelsea Girls was mostly completed. This was early September. A set had been built to look like a small room, and in it was a kind of throne/bed for Ondine. I don’t remember how many people were there, but Andy was at the camera and he asked me to hold the microphone, just out of camera range at the side of the "set." The film started rolling... This girl... starts this "confession" dialogue with "Pope" Ondine, and after a few minutes she calls him a “phony”. I think the second time she says this, Ondine gets visibly angry, screams at her, throws a glass of Coke at her, then lunges towards her and starts hitting her. By this time I felt sure that this was not "acting," as it were. I was quite scared, and saw that other people were backing away. I put the mic down on something and backed away myself, noticing then that Andy had also done so, leaving the camera running. I think the girl ended up running out screaming."

Like most of the people who hung out at the Factory, Morrissey was considerably younger than Warhol - ten years younger. He was born in Manhattan on February 23, 1938. Paul differed from many of Warhol's cohorts in one big way - he was against the use of recreational drugs.

Andy Warhol:

"Paul didn't take drugs - in fact, he was against every single drug, right down to aspirin. He had a unique theory that the reason kids were taking so many drugs all of a sudden was because they were bored with having good health, that since medical science by now had eradicated most childhood diseases, they wanted to compensate for having missed out on being sick. 'Why do they call it experimenting with drugs?' he'd demand. 'It's just experimenting with ill health!'" (POP118)

Paul was also not as promiscuous as many of the people who hung out at the Factory. In fact, nobody knew if he was gay, straight or neutral.

Andy Warhol:

"The running question was, did he [Paul Morrissey] have a sex life or not? Everyone who'd ever known him insisted that he did absolutely nothing, and all his hours seemed accounted for, but still Paul was an attractive guy, so people constantly asked, 'What does he do? He must do something...'" (POP119)

Morrissey was raised in Yonkers with his sister and three brothers. His father was a lawyer. His brothers ran small independent construction businesses. He was educated by nuns at the St. Barnabas School for eight years before continuing at Fordham University where he majored in English from 1955 - 1959. (FPM 13) Like future Warhol star Viva, Paul was educated at Catholic institutions, but whereas Viva rejected the conservative morality of the nuns and priests, Morrissey seemed to embrace it.

Paul Morrissey:

"Without institutionalised religion as the basis a society can't exist. In my lifetime, I've seen this terrible eradication of what makes sense and its replacement by absolute horror. All the sensible values of a solid education and a moral foundation have been flushed down the liberal toilet in order to sell sex, drugs, and rock and roll." (FPM13)

When Paul first joined the Factory in 1965, his initial duties included sweeping the floor (a Factory "tradition" for new cohorts), but he quickly got involved with helping Warhol make films.

Andy Warhol:

"When he'd introduced us, Gerard [Malanga] had said, "This is a friend of mine, Paul Morrissey, he's very resourceful." And right away Paul began coming by the Factory while we were shooting, to see how we did things and if there was any way he could get involved. At first he just swept the floor or looked through slides and photographs. He'd been wanting to start shooting sound movies himself, but he didn't have the money to rent all the sound equipment. He was fascinated to see our setup and he asked Buddy Wirtschafter, who was then our sound man, a lot of questions. Gerard was right, Paul was very resourceful - eventually to the point where he came to seem magical to us." (POP119)

Prior to his involvement with Warhol, Paul had made his own short films. One of the shorts he made while a senior at Fordham University starred his college friend Donald Lyons who would also become part of the Factory crowd.

Paul's moral attitude against drugs did not prevent him from filming people taking them. One of his early shorts showed two junkies shooting up - a theme he continued later when he directed Andy Warhol's Trash in which both Joe and Holly are shown injecting drugs.

Morrissey showed his short films in a small underground cinema he operated from a storefront in 1960 at 36 East 4th Street in the East Village of Manhattan. He would also show films by other directors, often borrowing them from the New York Public Library. One of the films he showed was Brian DePalma's first short film, Icarus. The police closed his makeshift cinema after a few months and Morrissey ended up first working for an insurance company and then the Department of Social Services.

The first Warhol film he saw was Sleep, which premiered at the Gramercy Arts Theater on January 17, 1964, where it ran for three days. Paul was friends with the projectionist - Ken Jacobs - who would later film the underground classic, Little Stabs of Happiness.

Paul left the screening of Sleep after a few hours, unimpressed by the film, and didn't see another Warhol film until more than a year later when he attended the premiere screening of Beauty No. 2 (paired with Vinyl) on July 12, 1965. It was at that screening that Gerard Malanga introduced Morrissey to Andy Warhol.

After joining the Factory, Paul became more involved in the films and would sometimes act as the in-house projectionist. When he showed More Milk Yvette he projected it on double screens - a technique they would later use successfully for The Chelsea Girls:

Paul Morrissey:

"We used a double screen for More Milk Yvette because the reels were too weak on their own. When they came back from the lab we screened them. Sometimes I loaded two projectors at the same time and if one was too boring I turned on the other at the same time, to get it over with. But once we stumbled upon this, we could see they worked better simultaneously. These were all simple ideas. They were not conceived as some grand artistic design." (FPM19)

Morrissey's double screen projection of More Milk Yvette was not the first time that the technique had been used. Warhol had previously utilized double screens for the Edie Sedgwick film, Outer and Inner Space.

In September of 1965, Morrissey was part of the group that Warhol took with him to Fire Island to help film My Hustler. Chuck Wein was also there - he had come up with the idea for the story of the film and attempted to direct it as well. Wein is credited as "director" of the film in the Jonas Mekas filmography of Warhol's movies. Wein wanted to incorporate camera movement and conventional editing in My Hustler as with a "real" movie. Although Warhol had used camera movement in several of his films already - including Camp, Space and Vinyl - he had become known for the stationary camera employed in films like Empire and the Screen Tests. According to Paul Morrissey, Wein had said to him, "We can't let Andy just turn the camera on and let it run - we're not just going to waste this whole trip. You operate the camera, and I'll tell them what to do, and we'll make something like a real movie with stops and starts." (FM234)

By the time The Chelsea Girls was made the following summer, Morrissey had begun taking a more active role in Warhol's filmmaking, effectively replacing Chuck Wein whose influence had diminished when Edie Sedgwick split with Warhol. Wein went on to work on the non-Warhol film Ciao Manhattan starring Edie and would also direct Rainbow Bridge featuring Pat Hartley who Warhol had shot for a Screen Test. Wein's role in the conception of Ciao Manhattan is noted in the end credits of the film which say "Black and white sequences are based upon a story by Chuck Wein and Genevieve Charbin."

After The Chelsea Girls, much of the footage that Warhol and Morrissey shot was included in **** (Four Stars) or The Twenty Five Hour Movie. Many segments of **** (Four Stars) would later be released as separate films including Imitation of Christ and The Loves of Ondine.

Paul Morrissey had come up with the title for The Loves of Ondine. Ondine was an opera fan and there was an Italian movie called Loves of Bellini at the time, so Paul changed "Bellini" to "Ondine" (JOE48).

It was while Morrissey and Warhol were filming a scene for The Loves of Ondine in the apartment of sixties journalist John Wilcock that they discovered their next superstar, an 18 year old ex-hustler who had previously served time for car theft in a correctional institute. It was...