Andy Warhol's Bike Boy (1967)

by Gary Comenas (2006/revised 2014/2015)

to filmography

Color/sound/109 mins

(filmed August 1967)

Ed Hood/Brigid Polk (Berlin)/Joe

Spencer/

Ingrid Superstar/Anne Wehrer/Viva

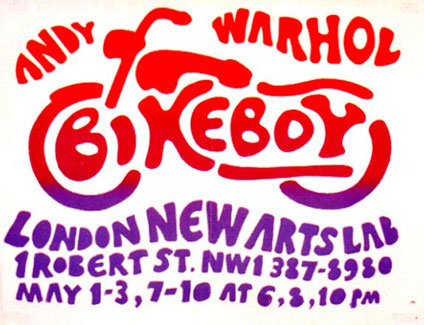

Although this poster for Bike Boy is dated 1968 on the "Underground Film Journal" website, London New Arts Lab did not move to Robert Street until October 1969 - see Luxonline here. If anyone is aware of the first screening of Bike Boy in the UK, contact me (click on "info" above).

Bike Boy, according to Andy Warhol, was the film that inspired Richard Gere to become an actor.

Andy Warhol (16 September 1979):

Went to Lester Persky's Yanks party at Trader Vic's. It turned out to be a really intimate dinner for only about fourteen people. Lester arrived with Richard Gere, and John Schlesinger arrived and Tommy Dean... Richard Gere said that ten years ago he came in on a bus from New Jersey and went to see our movie Bike Boy in the Village, and he said from then on he's been trying to be an actor - it took him eleven years, he said. (AWD240)

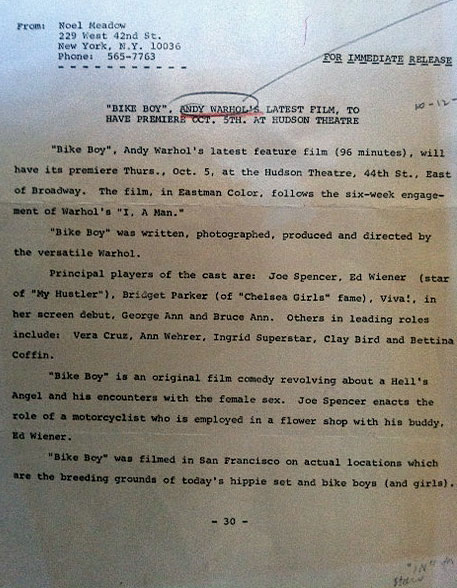

Bike Boy was shot during the summer of 1967 and opened at the Hudson Theatre near Times Square on 5 October of the same year after a six-week run of I, a Man at the same cinema. (FAW33)

The press release for the film claimed that it was shot "in San Francisco on actual locations which are the breeding grounds of today's hippie set and bike boys (and girls)."

Press release for Andy Warhol's Bike Boy

The "principal player," listed on the press release as "Ed Weiner," was actually Ed Hood. "Bridget Parker" was Brigid Berlin.

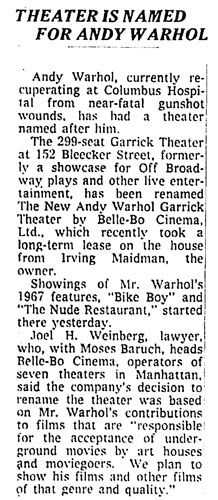

Originally, the film was 95 minutes long but the original print has never been found. The uncut full length footage originally shot for the film was included in the 25 hour version of **** (Four Stars). The footage from **** was later cut into a second, longer version of Bike Boy which opened in July 1968 at the New Andy Warhol Garrick Theater. It was the first film to play the theater after it had been renamed in Andy's honour while he recuperated in hospital from having been shot by Valerie Solanas - as noted in the New York Times.

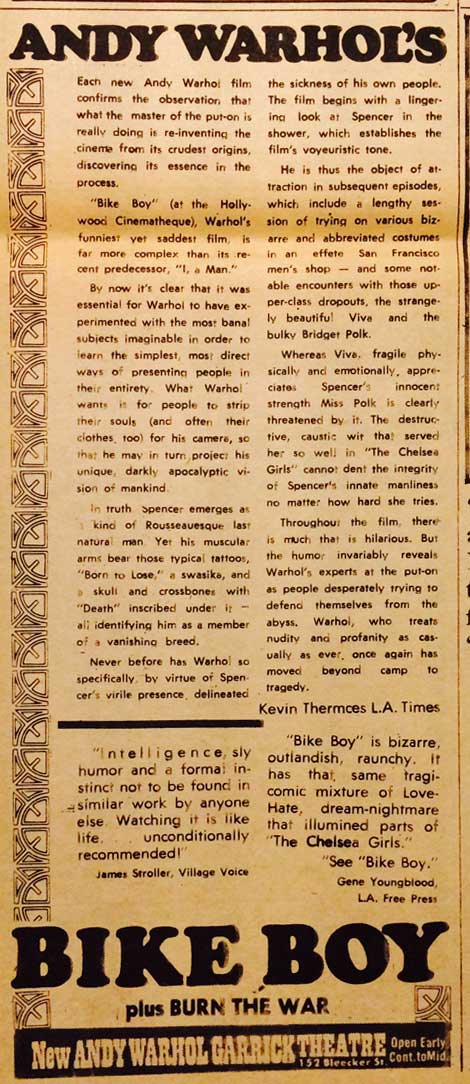

It is the version of Bike Boys that was shown at the New Andy Warhol Garrick Theater - the longer 109 minute version - which exists today. (FAW33) Although the New York Times aricle indicated that the film opened on a double bill with Warhol's The Nude Restaurant, the ad in the 18 July 1968 issue of the Village Voice advertised it as playing with something called Burn the War.

Village Voice ad, 18 July 1968

(Warhol Film Ads)

Burn the War was included in **** (Four Stars). Andrew Dungan (aka Julian Burroughs) describes Burn the War as "a short piece that allowed the artist Lil Picard, a longtime friend of Andy's to show her 'constructionist' art. She washed the American flag behind me as I spoke about what was wrong with America, a sort of half hour rambling speech." (See Andrew Dungan interview here.)

After Bike Boy's run at the newly renamed cinema, the second film to be shown at the New Andy Warhol Garrick Theater was Flesh, followed by Lonesome Cowboys.

In regard to the Hudson - where Bike Boy made its commercial debut the previous year - Tony Scherman and David Dalton noted in Pop: The Genius of Warhol (NY: HarperCollins, 2009) that Warhol began screening his films at the Hudson Theatre after its manager approached him for "sexploitation" films:

Tony Scherman/David Dalton:

"In early summer 1967, Maury Maurer, the manager of West 44th Street's Hudson Theatre, which specialized in racy features for gay men, approached Warhol and Morrissey. Maurer wanted Warhol films for the 'sexploitation,' or soft-core porn, market, a product of censorship's slackening grip." (SC382)

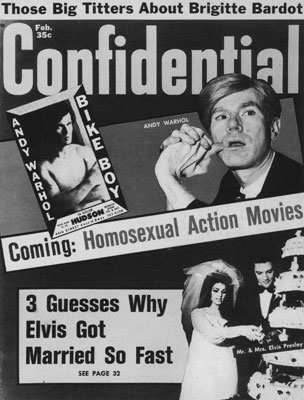

The first of the "sexploitation" films at the Hudson was My Hustler, followed by I, A Man (named after the classic 1965 porn film, I, A Woman), Bike Boy and Nude Restaurant. An ad for Bike Boy was featured on the front cover of the February 1968 issue of Confidential magazine to illustrate their article on "Homosexual Action Movies:"

David Bourdon (Warhol):

The February 1968 issue of Confidential, the scandal-mongering monthly magazine that claimed it "tells the facts and names the names," ran a photograph of Warhol and a Bike Boy ad on its cover in connection with an article headlined, "Coming Homosexual Action Movies." Reproducing ads for Bike Boy and My Hustler, the article claimed that the latter film signalled "the advent of a swarm of raw homosexual movies - aimed at both men and women sex deviates"... Andy, far from being embarrassed about appearing on the cover of Confidential (his relatives in Pittsburgh were mortified), thought it was "just great." (DB261)

Despite being labelled a "homosexual action movie" by Confidential, Bike Boy, as with Warhol's other "sexploitation" films, isn't very sexual. It's largely a series of conversations in which Warhol's superstars mock Joe Spencer - the bike boy.

J.J. Murphy (The Black Hole of the Camera: The Films of Andy Warhol):

Bike Boy begins with a close-up of Spencer's face. In a series of strobe cuts that focus mostly on his muscular upper torso and other parts of his body including his genital area, we watch Joe take a very long shower... Spencer then has a series of episodic encounters. In a clothing store two salesmen (art students Bruce Haines and George McKittrich) dress him in an outlandish outfit made of chains, so he ends up looking like a gladiator. They whip him lightly with a belt, deliberately prolong the measurement of the inseam on his pants, and spray him with fruity-smelling cologne... Besides the gay clothing salesmen, Ed Hood plays a florist. Pretending to be a friend, he ridicules the swastika on Joe's arm by connecting him via a Daily News headline to the slain American Nazi Party leader George Lincoln Rockwell, and reveals the fact that Joe doesn't actually have a working motorcycle. He also goads Joe into an outrageous description of engaging in bestiality with sheep." (JJM200)

There is no "bike" in this film. Just a bike boy. After his run-in with Hood, Spencer has scenes with a variety of female superstars - Ingrid Superstar, Anne Wehrer, Brigid Berlin and Viva. All mock him with subtle comments that he doesn't seem to realize are mocking him. But he does make an effort at defending himself with Viva and Brigid - he calls Brigid a lesbian and Viva a cold little bitch. Viva and Spencer attempt to engage in sexual activity without much success.

J.J. Murphy:

After a smoke, Joe disrobes Viva, who lies naked while he also strips. In various strobe cuts, Warhol has Spencer repeat the action of pulling off his pants. Joe stands up naked. The action repeats. He keeps giving Viva a drag from his cigarette, but as he stands, the limpness of his penis is obvious. The camera frames only his lower torso, emphasizing his buttocks as he stands over her. He then sits down next to her on the couch. We see his naked body in the foreground of the shot as Viva's hands embrace him and she looks up at him. She begins to laugh. When he asks why she's laughing at him, Viva tells him, 'I'm not laughing at you at all... Well, I'm just laughing because you're so funny' Joe responds, 'Funny? I ain't funny.' The film abruptly ends on his line. (JJM202)

Glyn Davis examines the film in reference to biker films in general in the British Film Institute's publication, Warhol in Ten Takes:

Glyn Davis:

Although Bike Boy 'fails' as generic biker film just as it 'fails' as sexploitation, the film's foregrounding of erotically charged imagery and flirtatious dynamics, and the ways in which its content nods to the subculture of bikers, inserts the film into a complex web of representations that harness together gay men and the macho iconography of the biker...

The history of the U.S. biker movie is relatively brief. Mainstream cinema's The Wild One (1953), starring Marlon Brando as the leader of a biker gang who harass the citizens of a small town called Wrightsville, set out of a template... The Wild One was followed by a small number of independently produced titles manufactured for the teenage market such as Motorcycle Gang (1957). The media coverage of the Hell's Angels in the mid-1960s, however, contributed to the development of a considerable, but short-lived biker film exploitation cycle. Roger Corman's The Wild Angels (1966) is usually identified as the inaugurating text of this group, with the mainstream success of the 'New Hollywood' film Easy Rider (1969), and its pessimistic conclusion about the countercultural dream, sounding its death knell. However, biker exploitation films continued to be made into the 1970s, becoming increasingly hybrid in form: The Black Angels (1970) is both blaxploitation and biker flick; the title of Werewolves on Wheels (1971) is self-explanatory; the extraordinary The Pink Angels (1971) features campy cross-dressing bikers en route to a cotillion. Although there has been the occasional title since this flurry of activity - both 'trash,' such as Chopper Chicks in Zombietown (1989) and mainstream, such as Wild Hogs (2007) - the main cycle crashed and burned by the mid-1970s." (GN91)

Davis also makes note of the inclusion of "elements of Nazism" such as Joe Spencer's swastika tattoo, writing "The Nazi/biker association is much more explicitly depicted in Kenneth Anger's avant-garde Scorpio Rising (1963)." (GN172) Warhol would definitely have been aware of Kenneth Anger due to the screenings of his films at Jonas Mekas' Film-Makers' Cinematheque and it may be that this served as an influence in regard to Bike Boy - although, as Davis points out, the "homoerotics of the biker culture" started before Scorpio Rising.

Glyn Davis:

Scorpio Rising may have been the first queer 'art' underground film to highlight the homoerotics of biker culture. However, the iconography of the biker - the stylised clothing, the homosocial male gang, the machines themselves - had for a number of years, already been eroticised by photographers and illustrators producing imagery specifically for subcultural consumption by a gay male audience. Some of the photographs taken in the 1950s by Bob Mizer and Tom Nicoll, working in the US and UK respectively, featured muscular men in various states of undress, standing next to or sitting astride motorbikes. Tom of Finland began drawing bikers in 1954; he regularly drew men on motorbikes, often decked out in full clone leathers." (GN173)

Coincidentally, one of the the people who posed for Mizer was Joe Dallesandro prior to his involvement with Warhol. Dallesandro made his debut in the Warhol film The Loves of Ondine which Callie Angell has also labelled a Warhol "sexploitation" film.

One could argue that Bike Boy says more about Warhol's superstars than it does about the bike boy. The way they subtly mock Joe Spencer as though he's not "in" with the "in crowd" also makes him seem more "real" than them. He lacks their hubris. Rather than the superstars mocking Spencer, could it be that Warhol was mocking the egos of his superstars? Was the joke on Spencer or on them? Who is more likable at the end of the film?

Bike Boy got a notoriously bad review in the New York Times:

MOVIE REVIEW

Bike Boy (1967)Screen: More Warhol 'Bike Boy' Opens at the Hudson Theater

By HOWARD THOMPSON

Published: October 6, 1967ANDY WARHOL is back with another of those super-bores, this one called "Bike Boy." It opened yesterday at the Hudson Theater. It belongs in the Hudson River.

Once more, a group of unappetizing young people slouch around in front of the camera, talking primarily about sex, directly or obliquely. The language is even filthier than in Mr. Warhol's "I a Man." The color is infinitely better, or less bad. The picture is carefully punctuated with nudity, primarily male and some of it complete.

The object of pursuit this time by the cast and a fascinated camera is Joe Spencer, a muscular youth with an angelic face and an early-Brando dese-dem-and-dose personality and vocabulary. Mr. Spencer is trying to find himself, see? All the others are trying to find him.

The picture opens with a kind of dressing-room male peep show as two purring homosexual clothiers watch some customers try on gaudy beach attire. Then in struts Mr. Spencer, as a motorcyclist. There is some perverse humor as the twittering clothiers flutter around the new customer. But for the remainder of the film, which uncoils for two hours, the hero babbles incessantly and obscenely about his sexual prowess, capacity and versatility. He also recounts in detail an act of bestiality.

Those in the film include Bettina Coffin, who was in "I a Man;" Ingrid Superstar, as a hearty Lesbian; Ann Wehrer as a Coke-swilling blonde and Vera Cruz as a food-obsessed neurotic. The prize nut of all, played by Viva, finally lands Mr. Spencer, which may account for the actress's name.

The fade-out shows the hero languidly and lovingly soaping himself under a shower. "Bike Boy" needs a lot of soap.

The Cast

BIKE BOY, written photographed, produced and directed by Andy Warhol. At the Hudson Theater, 44th Street east of Broadway. Running time: 96 minutes.

Motorcyclist . . . . . Joe Spencer

His Buddy . . . . . . .Ed Wiener

Fellow Cyclist . . . .Vera Cruz

Older Women . . . Ingrid Superstar and Ann Wehrer

First Salesman . . George Ann

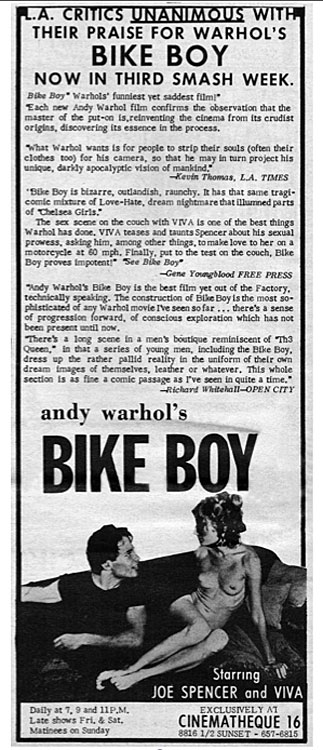

The reviews were apparently better in Los Angeles - judging from the comments that appeared on the ad when it played there:

Los Angeles Free Press, 19 July 1968

(Warhol Film Ads)

Cinematheque 16 was one of several arthouse cinemas that sprouted up in L.A. during the 60s. Film scholar David E. James gives a short history of the Cinematheque in his book, The Most Typical Avant Garde: History and Geography of Minor Cinemas in Los Angeles:

David E. James:

In the mid-1960s Los Angeles's alternative film culture was so strong that the eight-hundred-seat Cinema Theatre [where Sleep had made its L.A. premiere] was selling out every Saturday and Sunday night, and a parallel venue opened on Sunset Strip in June 1966. In 1964, Robert Lippard, an exploitation producer, had bought a theater with only 16 mm capability, intending to show nudie-cuties, but when Sunset Strip boomed as a mecca for the hippie culture, these proved unprofitable. Lewis Teague, an NYU graduate in film studies who had come to Los Angeles on an apprentice director program at Universal and had in fact directed an episode of the Alfred Hitchcock Hour for television, offered to manage it as an art house. Calling it Cinematheque 16, Teague began with weekly programs alternating between European art films and the emerging American avant-garde. The art films proved as unsuccessful as the nudie-cuties, but when advertised as "Psychedelic Film Trips," films by Brakhage Emshwiller, later Warhol, and locals including John and James Whitney, Stanton Kaye, and Peter Mays immediately knit into the local music and drug cultures and became very successful, easily sustaining a week's run for each program and, in the case of the Warhol films, becoming very profitable. Teague supplemented the regular schedules with open screenings (to which Jim Morrison brought his student films), and the other theater became an integral part of the Strip culture. Noting Teague's success, Frank Woods, a theatrical entrepreneur and producer, bought the theater and opened another Cinematheque 16 in Pasadena, which quickly failed, and in San Francisco, which became as successful as the one on Sunset Strip. In the late 1960s the Cinematheque 16 screenings and especially the midnight screenings at the Cinema Theatre were the sustaining institutions of the Los Angeles counterculture. (DJM225)

The year after Bike Boy played the Cinematheque 16, the leather-clad rock star who might be called the real bike boy (except that he usually didn't travel by motorcycle either), Jim Morrison, presented his poetry there. Recordings of the performance can be found on YouTube.

Popism notes that people would often confuse the star of Bike Boy, Joe Spencer, with Tom Baker who appeared in I, a Man. Baker died of a drug overdose in a shooting gallery in New York. It's not known what happened to Joe Spencer. (If you have any information on him contact me at garycom.now@gmail.com.)

[end]

Gary Comenas

(2002/rev. 2015)

warholstars.org

to filmography