Abstract Expressionism 1964

by Gary Comenas

In 1964 Barnett Newman paints Seventh Station, Eighth Station, Ninth Station and completes Be II; Jasper Johns has a retrospective at the Jewish Museum; Mark Rothko is commissioned to do the Rothko Chapel; Willem de Kooning receives a medal from the White House; Willem de Kooning is profiled in Vogue magazine.

* * *

Irving Sandler: "By 1964, it was clear that the economic situation of the artists had radically changed. Allan Kaprow published an article titled 'Should the Artist Be a Man of the World?' His answer was an emphatic yes. The Pollockian image of the heroic yet pathetic, rebellious drunken visionary had been replaced by the Warholian image of the artist..."

* * *

1964: Robert Motherwell is awarded the 4th Guggenheim International Award. (HM)

1964: Barnett Newman paints Seventh Station, Eighth Station, Ninth Station and completes Be II.

Be II was the last of the Stations of the Cross series. Newman began plans with Lawrence Alloway at the Guggenheim Museum in New York to show the series. (MH)

1964: Mark Rothko sells.

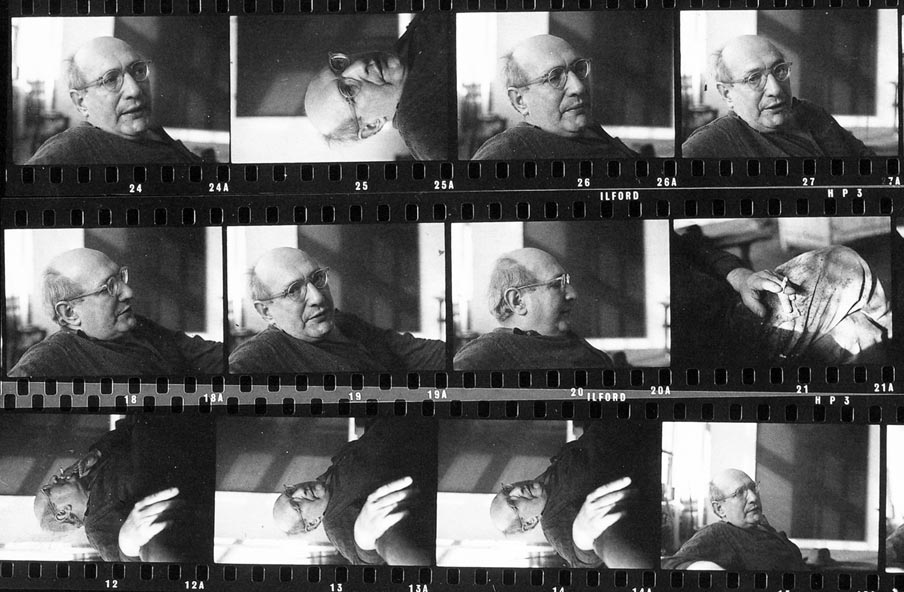

Contact sheet of Mark Rothko in his studio, April 11, 1964

(Photographer: Alexander Liberman © Getty Research Institute

Ben Heller bought Mark Rothko's Greens and Blue on Blue for $16,000. (RO639n27) Rothko also sold Ocher and Red on Red (1954) to the Phillips Collection. (RO640n28) (The painting became the fourth painting in their Rothko room.) (RO648n10)

1964: Willem De Kooning plans a retrospective.

Eduard de Wilde from the Stedelijk Museum in Holland visited Willem de Kooning in his Long Island studio to discuss the possibility of a retrospective. De Kooning agreed to the show providing that it did not travel to New York. (DK504) Frank O'Hara eventually got de Kooning to change his mind about the stipulation. Plans were made for the show to open in Holland in 1968 then travel to London after Holland and then to New York. (DK503)

Early January 1964: Joan Ward and Lisa moved back to New York.

Joan and Lisa moved back to the apartment on 3rd Avenue, remaining there for several years maintaining a distant contact with de Kooning who stayed in the Springs. (DK454)

February 1964: Jasper Johns retrospective at the Jewish Museum.

Johns was only thirty-four years old at the time. (RO430)

March 1964: Willem de Kooning receives doors.

De Kooning, who was fixing up his new studio in the Springs, received delivery of six doors that turned out to be be the wrong type. After being told he couldn't return them he decided to use them as canvases. (DK463/466)

April 10, 1964: Franz Kline's mother dies. (FK174)

April 23-June 7, 1964: "Post-Painterly Abstraction" at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

Clement Greenberg chose the artists except possibly the ones from California. According to John O'Brian who published Greenberg's exhibition catalogue text in The Collected Essays and Criticism, Volume 4, James Elliott, the curator of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art chose the California artists. The exhibition catalogue foreword, however, says that Fred Martin of the San Francisco Art Association arranged for Greenberg to see works in the San Francisco area.

The exhibition was Greenberg's attempt at categorizing the art which came after Abstract Expressionism. For Greenberg, Abstract Expressionism had " turned into a school, then into a manner, and finally into a set of mannerisms."

The artists in the exhibition were: Walter Darby Bannard, George Bireline, Jack Bush, Gene Davis, Ernest Dieringer, Thomas Downing, Ralph DuCasse, Friedel Dzubas, Paul Feeley, John Ferren, Sam Francis, Helen Frankenthaler, Frank Hamilton, Al Held, Alfred Jensen, Ellsworth Kelly, Nicholas Krushenick, Alexander Liberman, Kenneth Lochhead, Morris Louis, A. F. McKay, Howard Mehring, Kenneth Noland, Jules Olitski, Raymond Parker, Ludwig Sander, David Simpson, Albert Stadler, Frank Stella, Mason Wells and Emerson Woelffer.

After New York the show traveled to the Walker Art Center, Minneapolis (July 13-August 16, 1964) and The Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto (November 20-December 20, 1964).

Clement Greenberg [from exhibition catalogue text]:

The great Swiss art historian, Heinrich Wölfflin, used the German word, malerisch, which his English translators render as 'painterly,' to designate the formal qualities of Baroque art that separate it from High Renaissance or Classical art. Painterly means, among other things, the blurred, broken, loose definition of color and contour. The opposite of painterly is clear, unbroken, and sharp definition, which Wölfflin called the 'linear...'

The kind of painting that has become known as Abstract Expressionism is both abstract and painterly... Abstract Expressionism -- or Painterly Abstraction, as I prefer to call it -- was very much art, and rooted in the past of art. People should have recognized this the moment they began to be able to recognize differences of quality in Abstract Expressionism...

Abstract Expressionism was, and is, a certain style of art, and like other styles of art, having had its ups, it had its downs. Having produced art of major importance, it turned into a school, then into a manner, and finally into a set of mannerisms. Its leaders attracted imitators, many of them, and then some of these leaders took to imitating themselves. Painterly Abstraction became a fashion, and now it has fallen out of fashion, to be replaced by another fashion -- Pop art -- but also to be continued, as well as replaced, by something as genuinely new and independent as Painterly Abstraction itself was ten or twenty years ago.

The most conspicuous of the mannerisms into which Painterly Abstraction has degenerated is what I call the "Tenth Street touch" (after East Tenth Street in New York), which spread through abstract painting like a blight during the 1950s...in all this there was nothing bad in itself, nothing necessarily bad as art. What turned this constellation of stylistic features into something bad as art was its standardization, its reduction to a set of mannerisms, as a dozen, and then a thousand, artists proceeded to maul the same viscosities of paint, in more or less the same ranges of color, and with the same 'gestures,' into the same kind of picture. And that part of the reaction against Painterly Abstraction which this show tries to document is a reaction more against standardization than against a style or school, a reaction more against an attitude than against Painterly Abstraction as such...

...Right now it's Pop art, which is the other side of the reaction against Abstract Expressionism, that constitutes a school and a fashion. There is much in Pop art that partakes of the trend to openness and clarity as against the turgidities of second generation Abstract Expressionism, and there are one or two Pop artists -- Robert Indiana and the 'earlier' James Dine -- who could fit into this show. But as diverting as Pop art is, I happen not to find it really fresh. Nor does it really challenge taste on more than a superficial level. So far (aside, perhaps, from Jasper Johns) it amounts to a new episode in the history of taste, but not to an authentically new episode in the evolution of contemporary art.

Spring 1964: Joseph Hirshhorn and Harold Diamond clean de Kooning out.

Willem De Kooning had got to know the entrepreneur and art collector Joseph Hirshhorn at a dinner at Hirshhorn's mansion in Greenwich Connecticut in 1962. Both men came from working-class backgrounds. Afterwards, Hirshhorn declared to an interviewer, "I think de Kooning is the greatest painter alive today in America." (DK471)

Hirshhorn had previously purchased two de Koonings from the private art dealer Harold Diamond who was also at the dinner and later accompanied Hirshhorn on a trip to de Kooning's studio in the spring of 1964. According to Lee Eastman, a lawyer who advised de Kooning during sixties, Diamond and Hirshhorn arrived at the studio "with $10,000 in cash and booze and a $50 jacket and started to get de Kooning loaded. They cleaned him out. They got art worth $100,000 or more." (DK471) Hirshhorn bought about a dozen works including Queen of Hearts and some black and white paintings from the forties. (DK471) Hirshhorn wanted an ongoing arrangement with de Kooning whereby he would get the first pick of his new work. He bought more work from the artist in September. (DK472)

May 1964: Barnett Newman completes color lithographs.

Newman produced the lithographs in an edition of eighteen at Universal Limited Art Editions on Long Island, where he began working with lithography in 1963. The completed prints were titled 18 Cantos and dedicated to Newman's wife Annalee. The prints were unframed and unmatted and encased in a vellum box. (MH)

May - June 1964: Barnett Newman visits Europe for the first time.

Barnett traveled to Europe with his wife, Annalee, partly to supervise the hanging of Uriel in the home of British collector Alan Power. After staying in London for two weeks, the Newmans went to Basel, Switzerland; Colmar, Germany; and Paris and Chartres in France. (MH)

June 20 - October 18, 1964: "Four Germinal Painters" at the U.S. Pavilion of the 32nd Venice Biennale.

Organized by the director of the Jewish Museum, Alan Solomon, the four germinal painters were Jasper Johns, Morris Louis, Kenneth Noland and Robert Rauschenberg. Other artists included in the show were John Chamberlain, Jim Dine, Claes Oldenburg and Frank Stella. Rauschenberg became the first American to win the Biennale's International Grand Prize for Painting. (RO430)

Included 17 paintings from Jasper Johns from 1957 to 1964 and 3 sculptures by Johns from 1960. (JJ226)

1964: Mark Rothko moves his studio to East Sixty-ninth Street.

Mark Rothko's final studio was located at 157 East 69th Street, between Lexington and Third Avenues and cost $600 a month to rent. (LM61) William Scharf prepared the space while Rothko stayed in East Hampton (see entry below). It was in this studio that Rothko committed suicide in 1970.

c. Early/Mid 1964: Mark Rothko is commissioned to do the Rothko Chapel.

Rothko reserved his right to approve the architectural details of the yet-to-be built Houston Chapel (which would later be named the Rothko Chapel) when contracted to do the large paintings for the chapel. He was paid $250,000 which his accountant Bernard Reis recommended be staggered over four years for tax reasons. (LM62)

Dore Ashton [journal entry July 7, 1964]:

We went to the Rothkos for lunch. We sat on their porch [in East Hampton], overlooking the bay, little Christopher in his playpen, Mark looking with indescribably warmth at his child, watching lovingly as the baby clapped his hands while the Trout Quintet played... A lunch of appropriate small talk, then we went to the beach where Mark told me of his new studio, and his commission to do a Catholic chapel for the de Menils. He read, years ago, he said, the Patristic fathers (Origen for instance). He liked the "ballet" of their thoughts, and the way everything went toward ladders, he talked about making east and west merge in an octagonal chapel... He could never have done a synagogue, he said.

At the time of Ashton's visit, Rothko and his family were spending the summer at Amagansett, near East Hampton, Long Island. William Scharf, a painter who sometimes assisted Rothko, and his wife Sally stayed in the 95th Street house while Scharf prepared Rothko's new and final studio at 157 East 69th Street, between Lexington and Third Avenues. The studio was chosen specifically for working on the murals. Scharf built storage racks, constructed a three-wall mock up of the interior of the chapel and installed two pulley systems - one so Rothko could lower the paintings to work on them and one to adjust a parachute that was used to control the lighting in the room. Rothko would begin work on the Houston murals there in the fall and would work on them for three years - from 1964 to 1967. (RO465-8) During the last fourteen months of his life, after separating from his wife, Rothko would live alone in the front two rooms of the building. (RO467)

It was originally planned for the chapel to be part of St. Thomas University but its patrons, Paris-born John and Dominque de Menil moved their art (and their money) to Rice University in 1969, and the site of the still unbuilt chapel was moved from the campus of St. Thomas University and put under control of Houston's Institute for Religion and Human Development. (RO464)

Although Rothko did not sign the contract for the chapel commission until January 1965, he began working on the paintings in his new studio in the autumn of 1964 after returning from East Hampton. (RO466) According to Ulfert Wilke, Rothko had told him that he wanted "to make something you don't want to look at." (RO469) Scharf stretched the canvases (about "seventeen or eighteen"), mixed paints and did some underpainting, using housepainter's brushes and a dark colours ("brick reds, deep reds, black mauves"). Scharf recalled that the initial canvases were built up with "fifteen or twenty layers of paint." (RO468) After Scharf left, Rothko hired Roy Edwards and Ray Kelly as assistants who had been recommended by Theodoros Stamos. (RO469)

September 1964: Barnett Newman's wife retires.

After Annalee Newman retired from teaching, she would often spend her days with Barnett in his studio. (MH)

September 14, 1964: Willem de Kooning gets a medal from the White House. (DK468)

De Kooning, who was an illegal immigrant until March 1962 when he became an American citizen, received the Medal of Freedom. He flew to Washington with Ibram and Ernestine Lassaw and Susan Brockman and stayed in the Shoreham Hotel across the park from the White House. While other guests arrived at the White House in limousines for the ceremony, De Kooning arrived on foot, much to the amusement of the White House guard. (DK469)

September 1964: Joseph Hirshhorn buys more de Koonings.

This time Hirshhorn visited de Kooning's studio with his wife, Olga, and came away with thirteen works by the artist including Woman and Sag Harbor. Word leaked out about the purchases and when Time magazine called Hirshhorn in October to ask about an alleged purchased of $250,000 worth of art from de Kooning, Hirshhorn admitted that he had bought eight paintings, seven of them of women, and five drawings which he said were an addition to the dozen or so that he already owned. Hirshhorn also told them that "He's been working on a painting for six months that's already been purchased by me. I own it." He added, "If I ever have a museum, I'm going to have a de Kooning room." Approximately a month later, de Kooning sent Hirshhorn a list of people he owed money to, presumably because Hirshhorn had also promised to clear his debts. (DK472)

The private art dealer Harold Diamond, who advised Hirshhorn, came up with a novel way for de Kooning to earn more money, urging him to sell the newspapers and large sheets of vellum that de Kooning applied to the canvases to keep them fresh or preserve an image. He would normally throw the sheets away, but they contained transfers of the works, so Diamond told him to call them monoprints and sell them. De Kooning experimented with the sheets, moving the newspaper slightly on the surface of the canvas or making an intentional rippling effect in the paint that was then transferred. Diamond mounted some of the transfers on canvas and they were shown in a 1965 exhibition at the Paul Kantor Gallery in Los Angeles. (DK472)

As a sign of gratitude to Hirshhorn for his patronage, de Kooning gave him a work in 1967 inscribed, "Anything you want/anything I can/ to Joe/love Bill." (DK474)

October 1964: Allan Kaprow asks "Should the Artist Be a Man of the World?"

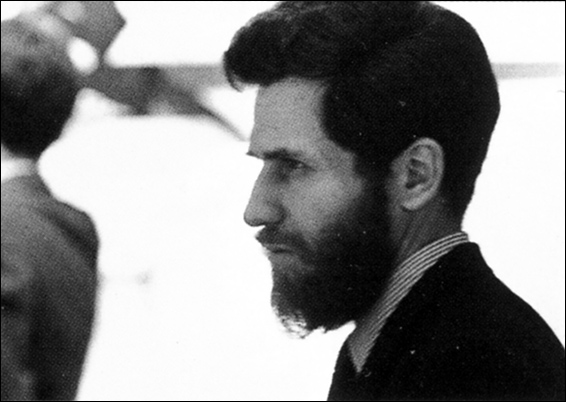

Allan Kaprow, NYC, 1965

Kaprow's article, "Should the Artist Be a Man of the World?" was published in the October 1964 issue of Art News.

Irving Sandler:

By 1964, it was clear that the economic situation of the artists had radically changed. Allan Kaprow published an article titled "Should the Artist Be a Man of the World?" His answer was an emphatic yes. The Pollockian image of the heroic yet pathetic, rebellious drunken visionary had been replaced by the Warholian image of the artist as socially adept celebrity and businessman... In his article, Kaprow wrote, "If the artist was in hell in 1946, now he is in business. The best vanguard artists are rich, just like the middle-class collectors they now socialize with and cultivate..." Thomas Hess who published Kaprow's article in Art News, attacked it in an editorial. He was particularly disturbed by Kaprow's comment that avant-garde artists should keep their middle-class collectors in mind while making aesthetic decisions. Hess asked, "wouldn't artists become alienated from their true beings or vision?," Kaprow countered by asking how artists could be alienated from their true being if that being was bourgeois. (IS245)

October 1964: Philip Johnson argues with Mark Rothko over the Rothko Chapel.

The actual chapel in Houston that was to house Rothko's paintings was, as yet, unbuilt.

From Mark Rothko: A Biography by James E.B. Breslin:

Philip Johnson had started with an ambitious and even grandiloquent design. He first conceived a square floor, the concrete building to be raised by several steps from the mall, placed on a platform, and topped by a high, pyramid-shaped tower, its apex severed in order to admit light through an oculus. Rothko first suggested adding an apse, then proposed transforming the square into the octagonal floor he mentioned to Dore Ashton in the summer of 1964. Rothko had admired the octagonal Byzantine church of S. Maria Assunta on the island of Torcello, near Venice...

In October 1964, Johnson, having accepted Rothko's floor plan, began developing a series of new designs for the building, and he would continue to do so over the next three years. He remembered the time, and his relationship with Rothko, as 'nothing but bad.' A dispute arose between the two men around the issue of the tower which, in some of its versions at least, resembled an Egyptian dunce cap. But Rothko did not object that Johnson's design was ugly or ludicrous. As always, Rothko was anxious about the lighting. Johnson imagined the harsh Texan light filtering down through the pyramid, then being diffused throughout the room. Rothko imagined his paintings displayed in a space as close as possible to the one in which they were being created. He wanted to model the lighting on that in his new 60th Street studio where, beneath the large skylight, he had hung a parachute which he could adjust to control the light. Johnson, moreover, imagined a vertical, visually prominent building, into which Rothko's paintings would have to fit. Rothko wanted a building that would fit his paintings, not usurp them. "Mark was very insistent as he went on that he did not want anything fancy or spectacular," Bernard Reis recalled. "He wanted a very simple envelope, octagonal in shape, something that would display the pictures because he did not want any stunts... He did not want anyone to feel that they would go to the Chapel because it was an architectural wonder."

... Eventually, Rothko appealed to the de Menils, who supported him. In 1967 Johnson resigned, and the project was then given to Howard Barnstone and Eugene Aubry, two Houston architects who adopted Rothko's suggestions and produced the present building, whose blank, mute, rectilinear facade echoes Rothko's paintings. (RO465-7)

Early October 1964: Barnett Newman travels to Seattle for a symposium of contemporary art.

The symposium, organized by curator Sam Hunter, was one of many occasions in the 1960s that Newman engaged critics and art historians in a public dialogue, saying that since "paintings can't be talked about, then the only thing to do is to try to talk about them." Annalee accompanied Barnett on the trip. (MH)

September 1964: Harold Rosenberg profiles Willem de Kooning in Vogue magazine. (DK469)

November 1964: Donald Judd writes about Barnett Newman.

Donald Judd's essay on Newman's work would not be published until 1970. In his essay, Judd noted the importance of "scale" in regard to Newman's painting:

Donald Judd:

It's important that Newman's paintings are large, but it's even more important that they are large scaled. His first painting with a stripe, a small one, is large scaled... This scale is one of the most important developments in the twentieth century art. (MH)