Abstract Expressionism 1955

by Gary Comenas (2009, Updated 2016)

1955: Robert Motherwell's second daughter, Lise, is born. (HM)

1955: Franz Kline lives in the East Village before moving to East 10th Street.

Kline lived on Avenue B near Tompkins Square for three months before moving to East 10th Street, east of 3rd Avenue where he lived for four or five months. Kline thought the East Village reminded him of England, but Dorothy C. Miller later recalled that Kline told her that he didn't like the East Village because it closed down early in the evening and was too far away from Greenwich Village. (FK179)

1955: Philip Guston joins the Sidney Janis Gallery. (MM90)

Previously, Guston had shown at the Peridot and Egan galleries, in addition to to his first solo show at the Midtown Gallery in 1945.(MM62) Between 1948 and 1956 Guston sold only two paintings. (MM90) With Janis' continued support, however, his paintings finally started to sell with "some regularity - the major paintings for as much as $2,500," according to Guston's daughter. (MM91)

1955: John Ferren becomes responsible for arranging the panels at The Club.

In 1956 Irving Sandler would replace him as program chairman. (IS101)

1955: Barnett Newman moves to Brooklyn Heights.

Newman and his wife moved from and wife move from their apartment on East 19th Street to 62 Pierrepont Street in Brooklyn Heights. (MH)

1955: Ben Heller buys Yellow, Green (1953) by Mark Rothko. (RO639n27)

When Heller, a clothing manufacturer, first saw the painting he thought it was so beautiful that "it couldn't be a good painting because we all know that modern paintings weren't so pretty and beautiful; they had to be kind of disturbing and difficult." (RO418/JP243)

Heller ended up paying $1,350 for the painting. Rothko initially wanted $1,500 but Heller had a budget of $1,000. They settled on $1,350, with Rothko arguing, "Look, it's my misery that I have to paint this kind of painting, it's your misery that you have to love it, and the price of the misery is $1,350." (By 1969, when Heller bought his eighth Rothko, the painting was worth $60,000.) (RO418)

Although Rothko had achieved a good price for the painting (at the time) he still lamented his financial situation.

Robert Motherwell:

... nobody has any conception of how poor we all were then. I remember maybe as late as 1955, you know, after the so-called triumph of Abstract Expressionism Rothko saying to me, 'If somebody would pay me $500 a month for all my past work, which constituted hundreds of pictures, plus everything I'll make in the future, I would gladly accept it in order to survive.' I remember looking him in silence because we knew - and this is in 1955 - that nobody in the world would pay him $6,000 a year for his total output; and he was married with a child in the most expensive city in the world. (SR)

January 2, 1955: "Nature and New Painting, by Frank O'Hara I" at the Club.

Moderator: John Myers. Panelists: Alfred Barr, Hilton Kramer, Frank O'Hara and Clement Greenberg. Philip Pavia described the evening as "Kramer used photographs of the 'Eight,' 1930s painters. (NE176)

January 14, 1955: "Zen and Psychoanalysis" at the Club.

Speaker: Dr. Martha Jaeger. Introduced by John Cage. (NE176)

January 15, 1955: Yves Tanguy dies.

Tanguy died of a cerebral haemorrhage. (SS416) After his death his wife Kay Sage lived alone in their Woodbury house and became increasingly depressed and alcoholic. She attempted suicide by overdose in 1959. Although she survived that attempt she killed herself after an unsuccessful operation for double cataracts in 1963 by shooting herself in the heart. Her ashes and those of her husband were scattered on the beach at Douamenez in Brittany by Pierre Matisse.

(SS421)

January 28, 1955: "Nature and New Painting, by Frank O'Hara II."

Panelists: Mike Goldberg, Grace Hartigan, Milton Resnick, Joan Mitchell, Frank O'Hara and Elaine de Kooning. Described by Philip Pavia as "New generation of painters." (NE176)

February 1955: Jackson Pollock breaks his ankle again.

Pollock had previously broken his ankle in 1954 when he and de Kooning fell into a ditch in the Springs while Pollock was visiting the "red house" (see Summer 1954). This time Pollock was wrestling in his living room with Cile Lord, a young realistic painter who had settled in the Springs. On February 14, 1955 the art dealer Martha Jackson wrote to Pollock "I hear you have broken your leg again" and told him that she wanted to buy some of his paintings. She drove to the Springs to look at his work and offered her car as payment. She got two of his "black" paintings for her dark-green 1950 Oldsmobile Convertible. (JP243)

February 4, 1955: Jazz at the Club. (NE176)

February 11, 1955: "Nature and New Painting by Frank O'Hara III" at the Club.

Willem de Kooning, Thomas B. Hess, Ad Reinhardt and Franz Kline. Philip Pavia described the evening as "Answer to O'Hara." (NE176)

February 12, 1955: "Immoral Husband" at the Club.

Described by Pavia as "a new play by James Merrill, poet. Presented by John Myers and the Artists Theater." (NE177)

February 18, 1955: Talk by Joe Liebling at the Club. (NE177)

March 4, 1955: Cafe night at the Club.

March 11, 1955: Folk Art: Movies of Japanese Prints, by Walter Lewisohn at the Club.

Introduced by Jeanne Miles. (NE177)

March 18, 1955: "Sculpture I" at the Club. (NE177)

March 25, 1955: "Sculpture II" at the Club. (NE177)

Moderator: Sidney Geist. Panelists: Day Schnabel, Albert Terris, Richard Stankiewicz, Clement Greenberg and Ibram Lassaw.

Described by Philip Pavia as "Sculpture should grow from a seed." (NE177)

April - July 3, 1955: "Fifty Years of American Art" in Paris. (NU)

The exhibition was organized by The Museum of Modern Art and took place at the Musée d'Art Moderne in Paris as part of the American sponsored "Salute to France" program.

Time magazine proclaimed, "Modern American art stormed through Paris last week, the advance patrol of a U.S. culture parade that before summer is out will treat Frenchmen to everything from Oklahoma! and Medea to the New York City Ballet, the Philadelphia Symphony, and a collection of some 60 French masterpieces on loan from U.S. collections. As lead-off event, Manhattan's Museum of Modern Art, setting up an advance base in Paris, staged a big show of modern art, including not only paintings and sculptures, but architectural exhibits, photographs, movies, prints, posters, and barrels of modern gadgets." (TA)

Opening night of the exhibition was attended by 2,500 guests. Sixty seven artists were represented in the exhibition which consisted of 108 paints and 22 sculptures. Time magazine noted that the "Contemporary U.S. abstract art proved almost too much to take. Among the sculptures, only Richard Lippold's shimmering construction of chromium and stainless-steel wires and Alexander Calder's familiar mobiles drew much appreciative comment. French artists took a hard, professional look at Jackson Pollock's chaotic drip paintings and Clyfford Still's brooding black canvas. But most Parisians, rocked by what they considered a meaningless world, gave up trying to find anything "American" in most U.S. abstractionists." Museum of Modern Art Director, Rene d'Harnoncourt was quoted as saying, "We didn't expect a miracle. Something would have been drastically wrong if a miracle had happened. But there is excitement in the air. When the museum guards were happy, I knew we had a success. Guards hate to be in an unpopular show." (TA)

The "collection of some 60 French masterpieces on loan from the U.S. collections" mentioned in the Time article referred to an American exhibition of 19th century French art running concurrently at the Musee de l'Orangerie. The show consisted of nearly 100 paintings and drawings of 19th century French art of paintings from the collection of American museums and individuals chosen by a committee of eight American museum directors headed by James Thrall Soby. (NU) French critics were kinder to that exhibition. The New York Times reported, "'Marvelous,' 'amazing,' and 'tremendous' punctuated critics' comments as they viewed paintings that are among the proudest possessions of American collections... The critics unanimously forecast the exhibition's success because Impressionist painting is much in vogue in France today. As in America, Van Gogh and Toulouse-Lautrec are favorites. The critics, however, singled out in particular works by Renoir, Manet, Courbet and Degas. Bernard Champigneulle of Figaro Litteraire said... 'We are not angry with Americans for having them but humble that we do not.'" (NU)

The same year The New York Times announced tours of major American orchestras in Europe through the International Exchange Program (I.E.P.) noting that "The orchestral tours are only part of an extensive program to show our friends in other lands that we have an active artistic life. It has finally been recognized in high quarters in Washington that the battle for men's minds and heart can be waged on the cultural front... The Russians have been busy in this area since the end of World War II." (NO)

April/May 1955: Mark Rothko's first show at the Sidney Janis Gallery. (RO336)

Rothko's first show at Janis was received enthusiastically by the press, although at least one reviewer, Emily Genauer in the Herald Tribune (April 17, 1955), thought that "Rothko's pictures get bigger and bigger and say less and less." Laverne George wrote in the May 1st issue of Art Digest, "The first impact of the 12 gigantic canvases on view is startling in its breadth, simplicity and the beauty of color dealt with on such a vast and subtly modulated scale. In Art News (Summer 1955), Thomas Hesse wrote that the exhibition was "one of the most enjoyable" in recent years and established "the international importance of Rothko as a leader of postwar modern art." (RO355/RO624f69)

Janis, like Parsons, let Rothko select which paintings would be shown in his shows and allowed the artist to hang them himself. Janis later recalled, "When we did the first show, he did every lick of work. He wouldn't let our staff do a thing." In a small room Rothko hung four large pictures two of which covered the walls from floor to ceiling. Janis recalled, "It was a terrific experience to walk into that room. It was just floating in luminosity - very breath-taking." (RO337-8) Whereas Rothko wanted bright lighting for his room at the "Fifteen Americans" exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, he wanted a dim light for his show at Janis. Janis thought the lighting "made the gallery so dismal, but he wanted some kind of mystery attached to his painting." When Philip Guston accompanied Rothko to one of his shows at the Janis, Rothko turned off half the lights in the gallery. (RO338)

In response to an invitation to the opening, Clyfford Still wrote Janis a scathing letter about Rothko:

Clyfford Still:

... for several years now I have been unable to avoid the morbid implications of Rothko's works, and the shrewd ambivalence of his verbalisms and acts. His need for sycophants and flattery, and his resentment of everyone, or every truth, that might stand in his path to bourgeois success, could no longer be ignored. In fact he was compelled to remind me of it one day when he grinned and announced that he 'never had any illusions that we ever had anything in common.' Be assured that it gave no pleasure, that afternoon three years ago, to be told that what I had considered to be gestures of concurrences were merely intended to conceal the claw of exploitation. (RO343)

On April 9, 1955 Barnett Newman also wrote a letter to Janis criticizing Rothko although it is not known whether he actually sent the letter. (RO622)

Barnett Newman:

I am frankly bored with the uninspired, or to put it more accurately, I am bored with the too easily inspired... This easy ability to be inspired not only reduces the concepts that form his [Rothko's] sources, not only distorts the act of painting itself, but it is so at variance with my own point of view that I can only reject everything it involves... It was Rothko who in 1950 said to me that he could not look at his work because it reminded him of death. Why should I look at his death image? I am involved in life, in the joy of the spirit. (RO345)

Newman thought Rothko had "subjugated" his [Newman's] work: "When Rothko returned from Europe, it is obvious that he 'saw' enough of this sense of life in my work to 'see' how he could subjugate it, just as previously he had 'looked' at the work of other artists for the same purposes." (RO345)

According to Newman's wife, Annalee, Rothko and Barnett "drifted apart" after the "Fifteen Americans" show when Rothko and Still did not push for her husband to be included in the exhibition. Still, according to Annalee, had told Newman that Rothko had actively sought to "keep him out." According to Sally Avery, other artists thought "it a little presumptuous on his [Still's] part to start painting." When his "zip" paintings were shown at Betty Parsons Gallery in 1950 and 1951, other artists had a mixed or even hostile reaction. Annalee recalls her husband feeling "betrayed," causing him to withdraw his work from Parsons' gallery and refusing to show again in New York until 1959. When he sent Newman and Still an invitation for the opening of the 1959 exhibition, he wrote on the invites "You are not invited to the opening." (RO346)

Rothko's first year at Janis would result in his largest income from painting so far. Prior to 1955, the most that Rothko made from his paintings was in 1950 when he earned $3,279.69 from sales. In 1955 he earned $5,471 (after the 1/3 gallery commission was deducted) from sales of his paintings. (RO229)

In February 1955, Rothko complained to Ethel Schwabacher, "The art industry is a million dollar one; 25,000 people, museums, galleries, etc. etc. etc. are supported by it: everyone gets money out of it except the artist. I can exhibit my paintings in a 100 different exhibitions. But I do not get any money. I can lecture. But they do not pay for lectures. I am written about, shown everywhere but do not even get $1300 a year." (RO338)

Although Rothko complained about his lack of money, he also had difficulty handling material success as his prices rose during the time he was with Janis. Janis thought that his new financial success "was a tragedy that he [Rothko] couldn't enjoy," later commenting that Rothko "was a poor boy all his life; he was a poor boy and he just couldn't get used to riches. That money problem was an albatross around his neck, like the ancient Chinese, the wealthy, who would carry these big stone pieces of money around their necks. It weighed him down.... It depressed him." (RO339)

April 8, 1955: "Sculpture IV" at the Club. (NE177)

April 13, 1955: Business meeting at the Club - members only. (NE177)

April 15, 1955: "Nature and Abstract Art" at the Club with speaker Frank O'Hara. (NE177)

April 22, 1955: "Nature and Abstract Art" with Nicolas Narsicano at the Club. (NE177)

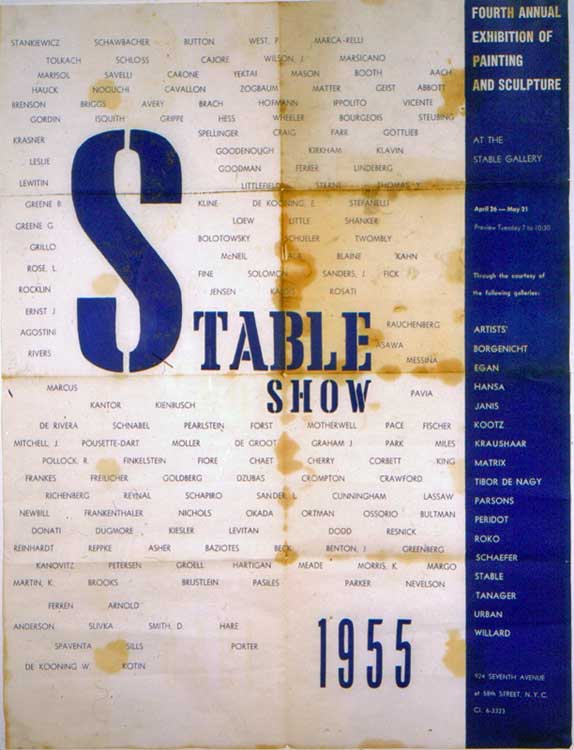

April 26 - May 21, 1955: The "Fourth Annual Exhibition of Painting and Sculpture" takes place at the Stable Gallery in New York.

Rauschenberg's combine painting, Short Circuit, was one of the works exhibited. (JJ125)

Jonathan Katz, "The Art of Code," from eds. Whitney Chadwick and Isabelle de Courtivron, Significant Others: Creativity and Intimate Partnership (London: Thames and Hudson Ltd., 1993):

Another combine of the same year called Short Circuit is literally a combination of the work of three artist friends within an armature provided by Rauschenberg. In this piece, submitted for an annual retrospective at the Stable Gallery, Rauschenberg protests the exclusion of these friends from the show by smuggling them in through his painting. The combine includes a Johns flag under one door, a painting by Weil under another, and a third image by his friend Ray Johnson. In addition, there is a program from an early John Cage concert and an autograph by Judy Garland. While the participation by friends and lovers is logical given the circumstances, the Garland autograph is a most curious addition, signaling the development of yet another new phase in Rauschenberg's art, a phase again tied to his relationship with Johns.

Spring 1955: "American-Type Painting" by Clement Greenberg appears in Partisan Review. (RO383)

In the article Greenberg commended Barnett Newman's work as "deep and honest" and "the most direct attack on [easel painting] so far." But he also portrayed Newman (to Newman's displeasure) as a follower of Clyfford Still and closely related to Rothko. (MH)

May 11 - August 7, 1955: "The New Decade: 35 American Painters and Sculptors" exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York.

In addition to work by Franz Kline, three Jackson Pollock paintings were included, including Blue Poles [Number 11, 1952] 1952. When Pollock noticed that the exhibition catalogue incorrectly stated that he had "worked for a time" with Hans Hofmann he rang the museum, cursed at a curator and received an apology from the museum director, John I.H. Baur. (JP244)

May 20, 1955: Cafe night at the Club. (NE177)

June 1, 8, 15, 29, 1955: Cafe nights at the Club. (NE177)

June 3, 1955: "Come as a Painting" party at the Club. (NE177)

Summer 1955: Jackson Pollock and Lee Krasner begin therapy. (PP328)

Pollock's therapist was a psychologist named Ralph Klein. Every Monday Pollock and Lee traveled to New York City to see their therapists. (JP245)

July 1955: Jackson Pollock gets a passport.

Pollock had never been outside the United States and was generally critical of Europe. Milton Resnick later recalled a conversation he had with Pollock when Pollock told him he was going to Europe:

Pollock: "What do you think? I'm going to Europe."

Resnick: "Okay, well, so?"

Pollock: "I don't know if I want to go."

Resnick: "What do you want to do?"

Pollock: "I hate art."

Resnick: "Sure. Everybody does. So you're going to Europe. What do you want me to tell you?"

Pollock never made it to Europe. He left the passport unsigned and never used it. (JP244)

July - end Summer 1955: Mark Rothko teaches at the summer session of University of Colorado in Boulder. (RO350)

The summer session lasted eight weeks and paid $1,800. When they reached Boulder they bought a used car which broke down on their way to the University. James Byrnes the director of the Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center had met Rothko in 1951 and had gone to Boulder to visit the artist, only to find him in the broken down car. In a letter dated July 7, 1955, sent jointly to Robert and Betty Motherwell and Herbert and Ilse Ferber, Rothko described the incident: "The car was guaranteed to take us enthusiastically to every point of wonder in the vicinity. It was eight miles up Boulder Canyon that our radiator gave out. We were waving our arms frantically for help and who stopped to help us? Gerry Levine, Mr. and Mrs. Byrnes, Inez Johnson and one dog. It was wonderful to see them, for the smell of their contact with you and of that Paradise, N.Y. still lingered about their clothes."

The radiator of the car had overheated. According to Byrnes, "it hadn't occurred to him [Rothko] that the car needed more than gas and oil to keep it going. He confessed that he had no interest in things mechanical and he would probably have abandoned the car had we not come along." (RO350)

Rothko was not particularly enthusiastic about the college and felt that the college was not particularly enthusiastic about him. He wrote to the Ferbers on July 14, 1955, "The silence is thick. Not a word or look from faculty, students, or the Fricks." He noted that "two of my paintings hang here for the last 3 weeks" and also noted that "One of them, on my first visit I found was hung horizontally. I phoned the hanger about his error. 'Oh it was no error,' he said. 'I thought it filled the space better.' I swear by the bones of Titian that this is true." (RO353)

September 26 - October 15, 1955: Lee Krasner exhibition at the Stable Gallery.

The solo exhibition featured Krasner's large collage paintings. (PP328) Around this time she changed her signature from "L.K." to her full name, Lee Krasner. (JP244) Eleanor Ward, the owner of the Stable Gallery had visited Krasner in the Springs to select the paintings. Krasner, Ward and Pollock went to dinner together and Ward was shocked when Pollock turned to her and said, referring to his wife: "Can you imagine being married to that face?" (JP245)

October 14, 1955: Cafe night at the Club - at its new address at 20 East 14th Street. (NE178)

November 18, 1955: Philip Pavia resigns from the Club to start It is. magazine.

A committee was selected to tak over the running of the club. Members of the committee were Leo Castelli, Herman Cherry, Kenneth Campbell, Nicholas Marscicano and Sid Gordin, with John Ferren as the president and Irving Sandler as an active participant in organizing panels. (NE131)

December 2, 1955: Dealers panel at the Club.

Moderator: John Ferren. Panelists: John Myers, Grace Borgenicht, Nat Halpert and Samuel Cootz. (NE178)

Winter 1955: Willem de Kooning denies he is an Abstract Expressionist.

De Kooning made the denial during a discussion panel at The Club to discuss Frank O'Hara's essay, "Nature and the New Painting." According to Irving Sandler, artists at the time were reevaluating the role of subject matter and "now claimed that a 'return to nature' was a viable option. Frank O'Hara became their champion." Sandler later recalled the conversation of artists attending the Club meeting:

Ad Reinhardt:

"All painting is abstract because it's constructed, including that of Constable and Courbet. They always talked about naturalism. I wonder what they meant."

Franz Kline:

"Corot today looks like a naturalistic painter, but in his day, they told him nature didn't look like that."

Willem de Kooning:

"Words and labels are very confusing. We need definitions. I'm not an Abstract Expressionist, but I express myself."

According to Sandler, "There were audible rumblings and gasps from the audience at de Kooning's denial of a label that was applied to him more than any other painter." (IS223-24)

November 28 - December 31, 1955: Jackson Pollock's third solo exhibition at the Sidney Janis Gallery. (JP328)

Pollock had not been painting much. He had completed only one painting in 1954 and two during 1955 - Search and Scent. He would complete no paintings in 1956. (JP239-40) Search was the last oil painting that Pollock would finish before his death. (PP328)

The exhibition was organized as a retrospective titled "15 Years of Jackson Pollock." It consisted of sixteen paintings including The Flame (1934-38), Pasiphaë (1943), Gothic (1944), Totem Lesson 2 (1945), The Key (1946), Eyes in the Heat (1946), White Cockatoo: Number 24A, 1948, Autumn Rhythm: Number 30, 1950, Echo: Number 25, 1951, Convergence: Number 10, 1952, White Light (1954), and Search (1955).

December 1955: Fortune Magazine publishes "The Great International Art Market."

The article was published in two parts - the second part in the January 1956 issue. It noted that the "art market is boiling with an activity never known before" and that for "the wealthy man, the ownership of art offers a unique combination of financial attractions" which included "a hedge against inflation... a route to legitimate income-tax reduction" and a means of reducing the "burden of inheritance taxes." (RO340) Old Masters were referred to as "gilt-edged security," Impressionists, Post-Impressionists and Picasso were "blue-chip stock" and works by contemporary artists (naming Mark Rothko as one of them) were "speculative or 'growth' issues." They predicted that a Rothko bought for $1,250 in 1955 would be worth $5,000 - 6,000 by 1960 and $25,000 - $30,000 by 1965. (RO341)

December 1955: Barnett Newman exhibits again.

He showed Horizon Light (then titled No. 7) in the Betty Parsons Gallery's tenth anniversary exhibition. It was the first time he exhibited since 1951. (MH)