Abstract Expressionism 1949

by Gary Comenas (2009, Updated 2016, 2020)

Philip Pavia: "The first half of the century belonged to Paris. The next half century will be ours." (DK292)

1949: Barnett Newman completes seventeen paintings.

It was the largest number of paintings that Newman would complete in a year. (MH)

1949: Robert Motherwell paints Granada, the first large painting in the Elegy to the Spanish Republic series. (MR132)

According to Motherwell, his Elegy to the Spanish Republic series grew out of a drawing he did for a planned second issue of Possibilities magazine. The first (and only) issue had been published c. autumn 1947. No second issue was ever published.

Robert Motherwell:

Sometime in the 1940's - I forget when - say, about 1947, when I was still editing books with Wittenborn and Schultz they told me that they'd like to put out an annual about the current scene and would I edit it... I said that I would be glad to do it if I could have some co-editors. The said, "Fine. Who do you want?" I suggested Pierre Chareau as the architectural editor; he was a French architect-in-exile with whom I had worked several years building a studio in East Hampton. I suggested John Cage to deal with music and dance. And Harold Rosenberg to deal with literature; and I would do the painting part. They found that agreeable. We brought out an issue. It was called Possibilities.

Then we were working on the second issue. In those days Harold Rosenberg regarded himself as really a poet. He was doing these other things 'incidentally' - the way I've always regarded myself as really a painter and doing these other things 'incidentally.' He wrote a very powerful, brutal, I would think Rimbaud-inspired poem. We agreed that I would handwrite the poem in my calligraphy and make a drawing or drawings to go with it and it was to be in black and white. So I began to think not only about getting the brutality and aggression of his poem in some kind of abstract terms but also that this was going to be reproduced in black and white. I worked for weeks getting the amounts. In painting really the whole issue of quality is quantities, is the amounts of black and white or thinness or thickness, fluidity,and whatever. I really conceived something that worked beautifully in black and white. It must have been at that time that Schultz was killed in the airplane and the whole project was dropped. I stuck the thing in a drawer in East Hampton. A year or two later I moved to New York to a little studio on Fourteenth Street. One day while unpacking I came across it and was able to look at it with detachment. I thought: God, that's a beautiful idea; I should make some paintings on the basis of that kind of structure...

One day I realized there was something really obsessional about it, that I would probably make many; that it had taken on a life of its own; and that it would no longer be legitimate to refer it merely to Harold's poem which indeed was the original impulse that it might indeed turn out to be possibly the main statement I would make in painting and therefore I would like to connect this with something that through associations reverberated in my mind as completely and as widely as the concept itself. And belonging to the Spanish Civil War generation I thought of that. I think maybe there was a transitional moment where I thought if it's going to refer to poetry it should be to Lorca. in fact, the first Elegy was originally called At Five in the Afternoon from the refrain out to Lorca's poem, the Death of the Bullfighter. Then one of the few times in my life that a lot of people talked to me about a picture was about that picture, and they would say, "I saw the most beautiful picture by you. I can't remember exactly the title. It has something to do with the cocktail hour or something." And suddenly I realized that five in the afternoon in New York means not the death of a bullfighter but a martini. And then I began to grope for a more generalized expression. the original ones were subtitles, I mean Elegy to the Spanish Republic (Granada) or whatever. And then that began to raise questions: does it really look like Granada, and so on... I mean to me subjectively in the sense that for us though the Spanish War was an issue of black and white, of lie and earth, an overture to the Second World War which we all knew was coming, and all the other things that are obviously involved. No, I don't regret doing it. I also suffered a lot. I've always been politically independent. I've never belonged to a political party. And for years it was taken for granted that I was a Communist." (SR)

1949: Robert Motherwell divorces Maria Emilia Ferreira y Moyers. (HM)

1948 or 1949: Franz Kline works with a Bell-Opticon projector at Willem de Kooning's studio at 85 4th Avenue.

Elaine de Kooning recalled this event as happening in either 1948 or 1949. Elaine would credit Kline's introduction to the projector as causing a "total instantaneous conversion to abstraction" by Kline and a complete change in his style in painting from figurative or semi-abstract work to full abstraction. (FK84) According to Kline's biographer Harry F. Gaugh, "If the Bell-Opticon made Kline aware of the potential for enlargement, he did not develop it fully until painting the 1949-50 canvases that made up his first one-man show." Some art writers have also credited The Museum of Modern Art's Klee exhibition (December 20, 1949 - February 19, 1950) with Kline's conversion to abstraction. Kline biographer Harry F. Gaugh viewed both theories with skepticism, later writing "the claim that MoMA's 1949-50 Klee exhibition had an 'immediate and decisive' impact on Kline must be viewed with as much skepticism as the Bell-Opticon 'instantaneous conversion' theory." (FK97)

Franz Kline [1955]:

Since 1949... I've been working mainly in black and white paint or ink on paper. Previous to this I planned painting compositions with brush and ink using figurative forms and actual objects with color. The first work in only black and white seemed related to figures, and I titled them as such. Later the results seemed to signify something - but difficult to give subject or name to, and at present I find it impossible to make a direct, verbal statement about the paintings in black and white. (FK106)

Richard Diebenkorn, visiting Kline's studio in 1953, "was impressed that the several current large paintings in the studio were exact blow-ups of very small sketches (telephone book pages), accidents and all." (FK85) Diebenkorn was surprised, having assumed previously that Kline's ideas had "evolved in terms of the scale and size of his canvases." (FK85)

According to Gaugh, "One of the first abstract paintings in which Kline tapped his potential for freewheeling expressionism is Untitled (Blue Abstraction) of 1949. Looping brushstrokes, planar overlays, and paint runs recall de Kooning's Light in August (c. 1946) and Black Friday (1948)." (FK84)

Harry F. Gaugh:

In the early 1940s Pollock had created such figural abstractions as Male and Female, Pasiphaë, and Gothic, problematic descendants of Surrealism. De Kooning's figural abstraction was also a response to Surrealism by way of Gorky and Picasso, as in Pink Angels (c. 1945) and Attic (1949). However, Kline's figural presences differ from Pollock's and de Kooning's in both appearance and process. They also derive directly from Kline's background in drawing, rather than from any response to Surrealism - Kline was less influenced by Surrealism than any other major artist of the New York School. Indeed, one can conceive of his abstraction without Surrealism as a precedent, impossible for work by his contemporaries. (FK106)

1949 - 1956: Mark Rothko paints vertically.

According to James E.B. Breslin in Mark Rothko: A Biography, "From 1949 to 1956 Rothko worked almost exclusively with oils on canvases that tended to be vertical and big, usually at least 6' high and 4' wide, sometimes as large as 9 1/2 x 8 1/2." (RO267)

January 1949: The second term of The Subjects of the Artist School begins.

Barnett Newman was added to staff. (RO263) Barnett and his wife, Annalee, helped to organize the school's friday night lectures. There were twelve speakers during the spring term, including Jean Arp, John Cage and Joseph Cornell. (MH)

January 1949: Peggy Guggenheim tries but fails to get Jackson Pollock a solo show in Paris. (PP323)

January 24 - February 12, 1949: "Adolph Gottlieb" exhibition at the Jacques Seligmann Galleries, New York. (AG173)

January 24 - February 12, 1949: Jackson Pollock's second exhibition at the Betty Parsons Gallery. (JP191/JF127)

The show consisted of twenty-six works painted in 1948 including (by current titles) Number 1A, Number 5,The Wooden Horse: Number 10A, Number 13A: Arabesque, White Cockatoo: Number 24A, and Number 26A: Black and White. Works on paper included Number 4: Gray and Red, Number 12A: Yellow, Gray and Black, Number 14, Number 15: Red, Gray, White, Yellow, Number 20, Number 22A and Number 23. Lee Krasner later explained why Jackson used numerical titles: "Numbers are neutral. They make people look at a painting for what it is - pure painting." (PP323)

Berton Roueché [from "Unframed Space," The New Yorker (August 5, 1950)]:

We asked Pollock for a peep at his work... "Help yourself," he said, halting at a safe distance from an abstract that occupied most of an end wall... "What's it called?" we asked. "I've forgotten," he said, and glanced inquiringly at his wife, who had followed us in. "Number Two, 1949, I think," she said. "Jackson used to give his pictures conventional titles: Eyes in the Heat and The Blue Unconscious and so on but now he simply numbers them. Numbers are neutral. They make people look at a picture for what it is - pure painting."

"I decided to stop adding to the confusion," Pollock said. "Abstract painting is abstract. It confronts you. There was a reviewer a while back who wrote that my pictures didn't have any beginning or any end. He didn't mean it as a compliment, but it was. It was a fine compliment. Only he didn't know it."

"That's exactly what Jackson's work is," Mrs. Pollock said. "Sort of unframed space."

Reviews of Pollock's show were mixed. Clement Greenberg wrote in the February 19th issue of The Nation, that Number 1A, 1948 was like the work of "a Quattrocento master." Emily Genauer wrote in the February 7, 1949 issue of the New York World-Telegram that Jackson Pollock's work reminded her of "a mop of tangled hair I have an irresistible urge to comb out." (PP323) Sam Hunter wrote in the January 30th issue of The New York Times that the show reflected "an advance stage of the disintegration of modern painting. But it is the disintegration with a possibly liberating and cathartic effect and informed by a highly individual rhythm." About a week later, Time magazine reprinted Hunter's comments with a large reproduction of Number 11, 1948, captioned "Cathartic disintegration," referring to Pollock as "the darling of a highbrow cult." (JP191)

Pollock completed approximately 32 paintings in 1948 with his canvases becoming increasingly larger. Summertime: Number 9A was 18 feet long. Number 5, 1948 was 8 feet tall. Rather than painting "allover" he now allowed the canvas to show through. (JP188)

Nine paintings sold at the show. The Museum of Modern Art bought its second Pollock - Number 4, 1948 for $250 (which it would trade the next year for Number 1, 1948). With the money from the sales he was able to finally install heating and hot water in the house in The Springs. (JP191)

Alfonso Ossorio paid $1500 for his Pollock "drip" painting (more than twice as much as anyone had previously paid for a Pollock). Betty Parsons had exhibited Ossorio's work in 1941 in a solo show at the Wakefield Bookshop and continued to exhibit his work at her own gallery for the next two decades. Lee Krasner suggested that Alfonso and his boyfriend, the dancer Ted Dragon, get a summer place in East Hampton. She took them househunting and they purchased the 70 acre Albert Herter estate where he would display the dozen or so works that he would purchase from Jackson Pollock over the next few years. He nicknamed the residence as The Creeks. (JP196) Ossorio became a frequent visitor to Jackson's place in the Springs. When he noticed that a painting he had purchased, Number 5, 1948 needed repairing he brought it to Jackson who, agreed. Jackson repainted the painting creating an entirely new image. (JP197) After various owners, Number 5, 1948, would become the most expensive painting in the world when it was reportedly sold for $140 million.

Alfonso Ossorio:

I hadn’t met Pollock, and it was simply by going to Betty’s gallery and seeing a show of his. I think it was as late as 1947 or ’48 that I suddenly realized the so-called drip panels had an intensity of organization, had a message that was expressed by its physical components, was a new iconography. I didn’t get all of this as coherently as I’m now saying it – it was a visual thought more than an analysis. And then I bought a painting, a big panel 8 x 4, of Jackson’s...

Jackson was very interested in – I remember being very surprised to see some twenty volumes of the proceedings of the Smithsonian Reports, obviously a battered old set he’d picked up somewhere which were full of 19th century renditions of American Indian art, everything from buffalo hide paintings, tepees, the sand paintings. But of course art history should open one’s eyes rather than close them. It should teach one – unfortunately it doesn’t – but it should teach you where your treasure is. However, the painting, the panel that I got from Betty of Jackson’s was damaged in its delivery. So I took it out to East Hampton and met Jackson that way. Well, it was the opening of a whole new world with the other artists in Betty’s gallery. For the very first time I was really living in New York and meeting my contemporaries. I had always missed it – had always been just around the corner. I suppose that after I left Harvard in 1938 I should have gone straight to New York. I didn’t and it’s probably just as well – there was precious little going on here then. Well, the summer of 1949 I spent in East Hampton. I saw a good deal of Lee and Jackson. I met him just after he had stopped drinking and so I knew him for two years as a teetotaler. I knew and saw most of him when he was not drinking at all... he was extremely silent most of the time. Drank gallons of coffee.... with Jackson one didn’t sit and have a long connected conversation. He would show the work, he would make very perceptive comments. His vocabulary was psychoanalytical in the sense that he had been in analysis and his intellectual vocabulary was based on that rather than on aesthetics or art history or philosophy. (OS)

February 1949: Josef Albers exhibitions at the Egan and Janis galleries. (FK98)

Kline biographer Harry F. Gaugh would later consider Albers' work as a possible influence on Franz Kline in regard to Kline's use of the square.

Harry F. Gaugh:

Josef Albers offered another source for Kline's adoption of the square as a major leitmotif. In February 1949 two Albers shows ran simultaneously at the Egan and Janis galleries, with early black and white works in the Egan section. Speaking of Albers, well known for his Homage to the Square series, Kline remarked, "It's a wonderful thing to be in love with The Square." (FK97-8)

Other possible influences that Gaugh mentions for Kline's squares or rectangles include "Picasso's paintings of the late 1920s, such as The Studio (1927-28), which hung in the Museum of Modern Art;" Paul Klee's The Cupboard and Kettledrummer of 1940; Mondrian's Composition 1A in the collection of Hilla Rebay shown late 1949 at the Janis Gallery and Adolph Gottlieb's Romanesque Facade. (FK96-7)The artist Nicholas Marsicano told Gaugh in 1970 that Kline had once told him that "Two squares can be two of the saddest eyes in the world." (FK98/172fn50)

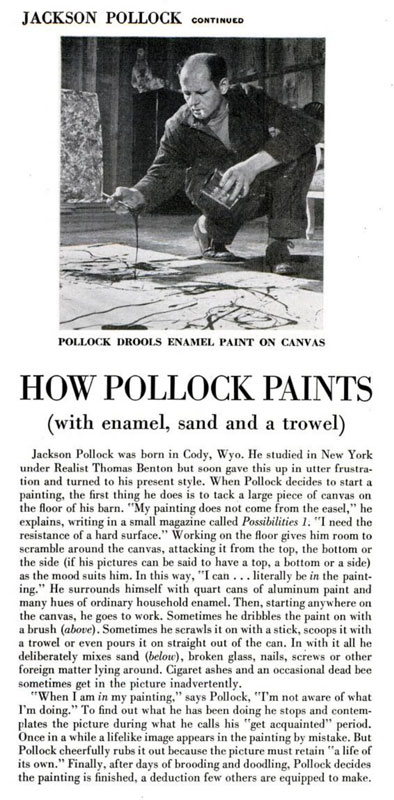

February 1949: Jackson Pollock is photographed by Arnold Newman for Life magazine.

Jackson demonstrated his painting process, including the addition of sand to his canvas. He also asked Newman if he could "borrow" $150, offering him a painting in exchange. Newman declined, explaining that he was saving his money for his marriage the next month. (JP193) Pollock was interviewed for the article at the offices of Life magazine. Dorothy Seiberling, the editor of Life, recalled, "He talked but you felt it was agony for him. He twisted his hands. Lee had to amplify whatever he said." When asked why he didn't paint realistically, Pollock answered, "If you want to see a face, look at one." When asked about hostile critics, he answered, "If they'd leave most of their stuff at home and just look at the painting, they'd have no trouble enjoying it. It's just like looking at a bed of flowers. You don't tear your hair out over what it means." His comments were never printed. (JP193)

February 1949: Willem de Kooning makes his first public statement about art. (DK277)

"A Desperate View" was the name of de Kooning's talk at the Subjects of the Artist school.

Willem de Kooning [from "A Desperate View]:

My interest in desperation lies only in that sometimes I find myself having become desperate... In Genesis, it is said that in the beginning was the void and God acted upon it. For an artist that is clear enough. It is so mysterious that it takes away all doubt. One is utterly lost in space forever... The idea of being integrated with it is a desperate idea... The only certainty today is that one must be self-conscious. The idea of order can only come from above. Order, to me, is to be ordered about and that is a limitation. An artist is forced by others to paint out of his own free will. If you take the attitude that it is not possible to do something, you have to prove it by doing it... It is impossible to find out how a style began. I think it is the most bourgeois idea to think one can make a style before hand. To desire to make a style is an apology for one's anxiety... The subject matter in the abstract is space. He fills it with an attitude. The attitude never comes from himself alone. (AT582)

March 15 - April 12, 1949: David Hare, Sculpture exhibition at the Julien Levy Gallery. (MA312)

March 28, 1949: Mark Rothko exhibits his multiforms at the Betty Parsons Gallery.

It was at Rothko's third show which opened at the Parsons' gallery on March 28th that he first exhibited his multiforms. Herbert Ferber later commented that ""From the time he [Rothko] began to leave the Surrealist phase he did what he once described to me as avoiding subject matter to the extent that if he saw something in one of his paintings that resembled an object, he would change the shape." (RO233) Five of Rothko's multiforms were reproduced in the October 1949 issue of The Tiger's Eye with a statement by the artist.

Mark Rothko (The Tiger's Eye, October 1949):

The progression of a painter's work, as it travels in time from point to point, will be toward clarity, toward the elimination of all obstacles between the painter and the idea, and between the idea and the observer. As examples of such obstacles, I give (among others) memory, history or geometry, which are swamps of generalization from which one might pull out parodies of ideas (which are ghosts) but never an idea in itself. To achieve this clarity is, inevitably, to be understood. (RO246)

The show included eleven paintings priced at $100 to $3000, although the highest priced painting, Number 1, 1949, was already owned by Mrs. John D. Rockefeller IIII who had purchased it on January 4, 1949. (RO609) During the winter 1948/49 the architect Philip Johnson was building a guest house on East 52nd Street for the Rockefellers and was advising Mrs. Rockefeller on the purchase of art for the new building. Johnson took her to Rothko's small apartment, along with Dorothy Miller and Alfred Barr and Mrs. Rockefeller bought the painting for $1,000. Miller recalled that due to the small size of his apartment, Rothko "had such difficulty showing us the paintings." (RO254/RO609n57)

Rothko named his paintings with numbers rather than names - similar to Still and Pollock. Still had explained his reasons for using numbers to Betty Parsons in March 1947: "The pictures will be without titles - only identified by numbers. Risking the charge of affectation I am omitting titles because they would inevitably mislead the spectator, and delimit the meanings and implications latent in the work." (RO606n25) Many of Rothko's paintings also reflected the trend toward larger canvases. Number 1, 1949 measured 5 1/2 feet by 4 1/2 feet.

Mark Rothko [Pratt Institute lecture 1958]:

Large pictures take you into them. Scale is of tremendous importance to me - human scale. Feelings have different weights; I prefer the weight of Mozart to Beethoven because of Mozart's wit and irony and I like his scale. Beethoven has a farmyard wit. How can a man be ponderable without being heroic? This is my problem. My pictures are involved with these human values. This is always what I think about... I think that small pictures since the Renaissance are like novels; large pictures are like dramas in which one participates in a direct way. The different subject necessitates different means. (RO396)

Margaret Breuning (M.B.) reviewed the show in The Art Digest (April 15, 1949): "The unfortunate aspect of the whole showing is that these paintings contain no suggestions of form or design." Thomas Hess in Art News (April 1949) gave credit to Rothko for his "strength of composition" but also criticized his "insistence on making the grand gesture" with his immense canvases, commenting that "The very ambition which went into covering such immense surfaces, the very refusal to exploit the full resources of the oil medium, has resulted in the ambiguity of the decoration which cannot be decorative." (RO247)

Harold Rosenberg was disappointed by the exhibition. Paintings which Rothko had shown him in July of 1948 in East Hampton were not in the show. Rosenberg felt that the paintings at the Parsons' show "didn't have any of the variety and surprise" and were "simplified versions" of the work that Rothko had previously shown him. When Rothko asked Rosenberg what his reaction was to the show, Rosenberg told him "I thought it was lousy" and asked him "What the hell happened to all those terrific paintings you did at Louse Point?" According to Rosenberg, Rothko told him that "he had talked to a friend and they had decided there was too much variety and that he should do something more identifiable." (RO248)

Two oil paintings were sold from the show. One went for $100 and one was sold for $600 to Rothko's friend, the sculptor/architect Tony Smith. (RO253) According to Lee Seldes in The Legacy of Mark Rothko, Rothko's total income for 1949, including his teacher's salary, was $3,935. (LM25))

Spring 1949: The third (and final) term of The Subjects of the Artist School: Studio 35 begins. (RO263/IS26)

According to the Barnett Newman Foundation's chronology, the school closed in May 1949. (MH) During the final term of the school, a series of twelve Friday evening seminars were added, "each to be conducted by an advanced artist or intellectual" with Robert Motherwell moderating. (RO263) The public was invited to the seminars, with attendance averaging 150. Among the speakers were Joseph Cornell who presented three rare films; John Cage gave a lecture on Indian sand painting, Richard Huelsenbeck spoke on "Dada Days," art dealer Julian Levy spoke on "On Surrealism in America;" Willem de Kooning "On The Desperate View;" Adolph Gottlieb on the "Abstract Image;" Ad Reinhardt on "Abstraction." (RO263/IS27)

When the school closed at the end of this term, the Friday lectures continued as "Studio 35." (RO263)

Irving Sandler:

... the programs were continued by a group of New York University professors who, in order to provide working space for their students, rented the loft and renamed it Studio 35... The final activity of Studio 35 was a three-day closed conference, April 21 - 23, 1950. The proceeding were stenographically recorded, edited by Motherwell, Reinhardt and Goodnough, and published in Modern Artists in America (1951). In the introduction to this publication, the reason for the decline of Studio 35 is given: "These meetings... tended to become repetitious at the end, partly because of the public asking the same questions at each meeting." (IS27)

April 1949: Life magazine publishes photographs of Communist sympathizers.

From Who Paid the Piper? by Frances Stonor Saunders:

In April, Henry Luce, owner-editor of the Time-Life empire, personally oversaw a two-page spread in Life magazine, which attacked the degradations of the Kremlin and its American "dupes." Featuring fifty passport-sized photographs, the piece was an ad hominem attack which prefigured Senator McCarthy's unofficial blacklists. Dorothy Parker, Norman Mailer, Leonard Bernstein, Lillian Hellman, Aaron Copland, Langston Hughes, Clifford Odets, Arthur Miller, Albert Einstein, Charlie Chaplin, Frank Lloyd Wright, Marlon Brando, Henry Wallace - all were accused of toying with Communism. This was the same Life magazine which in 1943 had devoted an entire issue to the USSR, featuring Stalin on the cover, and praising the Russian people and the Red Army. (WP52)

Summer 1949: Mark Rothko teaches at the California School of Fine Arts in San Francisco. (RO222)

Rothko had previously taught at the school in the summer of 1947. While he was in San Francisco in 1949, Clyfford Still loaned Rothko his 1948-49-W No. 1 which Rothko hung in his bedroom for the next six years until Still asked for it to be returned. (RO223)

The artist Ernest Briggs was a student in Still's class when Still introduced Rothko to the students.

Ernest Briggs:

I first met Rothko - Still brought him into the class and introduced him. And there was of course a total difference in terms of personalities. Rothko was the epitome of the New York Jewish intellectual artist/painter and exuded an entirely different kind of energy [than Still]; urbane, deep intent, quintessential New Yorker... The big thing with Rothko's presence there in the program was that he gave a lecture once a week which was in a separate room and people came who were not even in the painting class came to listen to the lectures. Which again, was not a lecture. It was more like a conversational thing, responding to a few questions and then going on... I can remember when he was in the earlier period, the so-called Surrealist period, he mentioned that he and his particular group, Gottlieb and Baziotes, were influenced by and very close to classical studies, classical mythology, and he would be quoting Herodotus or something at some of these lectures or repeating an antidotal story of Herodotus in answer to some inquiry on the part of a student. (EB)

Summer 1949: Barnett Newman and wife, Annalee, travel to Akron, Ohio to visit Annalee's parents. (MH)

Barnett and Annalee also visited the prehistoric Native American mounds in the southwestern and central part of Ohio. The trip inspired Newman's essay "Prologue for a New Aesthetic" (not published during his lifetime).

Summer 1949: Adolph Gottlieb helps start Forum 49 in Provincetown.

Forum 49 was started by the poet and painter Weldon Kees, writer Cecil Hemley (Gottlieb's cousin) and the painter Fritz Bultman. The weekly forums were held on Thursday evenings at Gallery 200. Participants included Karl Knaths and Hans Hofmann. Gottlieb was involved in the formation. (AG47)

Summer 1949: Philip Guston's wife joins him in Italy.

While she stayed with Philip for four months in Italy, their daughter Musa was left in Woodstock.

Musa Mayer [c. 1988]:

It is only recently that my mother and I have begun to talk about this time. "I shouldn't have left you," my mother tells me now, "but when Philip wrote and asked me to come, I didn't think of you. I thought only of being with him, that he wanted me with him." "Couldn't you have taken me with you?" I ask. My mother looks at me, aghast. "Taken you? Oh, I wouldn't have known how. Philip didn't want you there." "But that's terrible," I say... Now it is my mother who seems irritated, defensive, as if I have attacked what is unassailable. "Terrible? But why? He was an artist. That was simply who he was."

... The first part of that long summer I spent up on the mountain, in Byrdcliffe, at a place called the French Camp, a sort of boarding school where no English was permitted... Later in the summer, I was take to St. George's, a church camp on the Hudson River... "You were always so lively before," my mother says. "Curious about everything, and friendly. But when we came back you were subdued, somehow." (MM41)

During his year in Italy Guston only painted "sporadically" according to his biographer, Dore Ashton. Although, according to Ashton, he drew "constantly" in Rome, none of the drawings survive. There are, however, in existence a few drawings he did on the Italian island of Ischia. (DA82)

June 1949: Jackson Pollock signs contract with Betty Parsons.

Terms were similar to Pollock's previous contract with Peggy Guggenheim. The new contract with Parsons was valid through January 1, 1952. (PP323)

June 1949 - Spring 1950: Jackson Pollock works in the studio of Roseanne Larkin.

Pollock made terra-cotta sculptures in his East Hampton neighbour's apartment where he would work off and on until Spring 1950. (PP323)

July 1949: Willem de Kooning is arrested for indecent exposure in Provincetown.

Elaine and Bill had rented part of the ground floor of a small cottage in Provincetown during July. The painter, Sue Mitchell, who was having a relationship with Clement Greenberg, rented the other part of the ground floor. Above them was the son of the owner of the Galerie Maeght in Paris. According to de Kooning's biographers, Mark Stevens and Annalyn Swan, it was in Provincetown that Joop Sanders "first saw de Kooning drink heavily and he sensed a new intensity in the partying spirit of the art world." During one visit Elaine told Joop that another artist had gone to the beach with Bill after a drinking session and she was worried about them because a storm had been forecast. Joop went down to the beach to look for them and found them "unbelievably drunk" and "still drinking." The artist with Bill was so drunk that he passed out. Bill and Joop decided to get him into the ocean to sober him up and as there was nobody else on the beach and didn't have bathing suits with them, they took off their clothes and dragged the drunken artist into the water. When they returned to the beach they were met by a state trooper who arrested them for indecent exposure and put them in separate jail cells to sober up. Joop and Bill were fined five dollars each. Their artist friend was charged with resisting arrest with bail set at forty dollars which Hans Hofmann lent the artist. (DK284-5)

During this summer, de Kooning painted Sailcloth and Two Women on a Wharf. (DK285)

August 1949: Detonation of an atomic bomb by Russia. (WP58)

August 3 - October 5, 1949: "Sculpture by Painters" exhibition at The Museum of Modern Art. (PP323)

Jackson Pollock exhibited two sculptures in the exhibition organized by Jane Sabersky. The show traveled to twelve U.S. cities from November 1949 to May 1951. (PP323)

August 6, 1949: James T. Soby ask "Does Our Art Impress Europe?" in the Saturday Review.

From "Does Our Art Impress Europe" by James T. Soby [American Review, August 6, 1949]:

We have produced in painting and sculpture no figure big enough to hold the eyes of the world on himself and also inevitably, on those of lesser stature around him. Even so, we can take hope from a curious fact about giants in the arts: when you get one, the rest come easily. We await our first in painting and sculpture, certain that he will appear and others after him.

Mr. Soby didn't have to wait long. Two days later Life magazine published their famous article on Jackson Pollock.

August 8, 1949: Life magazine asks if Jackson Pollock in the greatest painter in the United States.

The article titled "Jackson Pollock: Is he the greatest living painter in the United States?" was written by Dorothy Seiberling and included photographs of Pollock at work by Martha Holmes and Arnold Newman's famous photograph of Pollock standing in front of Summertime: Number 9A 1948. (PP323)

It also included a small section explaining Pollock's painting methods:

Life magazine, August 8, 1949

If America didn't know about Pollock they certainly did after this article. Life at the time had a circulation of about 5 million. The residents of the Springs who knew Jackson were shocked to see him in the magazine. Dan Miller who ran the local general store, recalled that "A good many of them made peace with themselves by figuring that Life magazine was crazier than Pollock." (JP194)

The article presented Pollock as a paint-slinging cowboy from Cody, Wyoming. The town's newspaper, the Cody Enterprise, launched an investigation into Pollock's background because nobody in the town had heard of him. (JP194)

James Brooks and Bradley Walker Tomlin brought copies of the article to Pollock in the Springs but later recalled that Pollock refused to look at it while they were there. But Pollock would keep stacks of the magazine on a shelf and show them to visitors. Soon after the article appeared, Jackson bought a used 1941 Cadillac convertible costing $500. (JP195)

According to Milton Resnick, when Willem de Kooning saw the article and the photos of Jackson, he commented "He looks like some guy who works at a service station pumping gas." (DK285)

From How New York Stole the Idea of Modern Art by Serge Guilbaut:

In 1949, shortly after the publication of the Life article on Pollock... sales increased at an incredible pace. In October four paintings were sold to the wealthy painter Alfonso Ossorio. Thirteen more were sold at $3,600 during a one-man show judiciously held from November 21 to December 10. The year proved a profitable one, since Pollock sold thirty-five canvases for a total of $13, 870 ($4,578 of which went to the gallery). Apparently everybody got into the act, including many famous collectors who did not hesitate to invest in Pollock, such as John D. Rockefeller, Ossorio, Edward Root (£3,200), Lee Ault (president of Quadrangle Press, $1,900), Russel Cowles, The Museum of Modern Art, Duncan Phillips ($2,000), Grace Borgenicht, and institutions such as Vogue magazine and Carnegie Illinois Research Laboratory. In the following year Pollock sold for $13,600 and Rothko for $8,950. Note,too, that after the war large collectors started buying from Parsons. In 1945 Root bought Stamos and Rothko; other buyers included Alex M. Bing (real estate), Emily Hall Tremaine (art director of the Miller Co.), and Lynn Thompson.

At $8,950 per year, these artists were not on the brink of poverty, despite the still current myth about their financial difficulties. Recall that in 1951 fifty-five percent of American families fell below the poverty line of $4,166 for a family of four... In 1948 two-thirds of all American families lived on less than $4,000 per year. (SG242-3n50)

August 16, 1949: Republican Congressman George A. Dondero labels artists as Communists in speech to Congress.

George A. Dondero:

Mr. Speaker, quite a few individuals in art, who are sincere in purpose, honest in intent, but with only a superficial knowledge of the complicated influences that surge in the art world of today, have written me - or otherwise expressed their opinions - that so-called modern or contemporary art cannot be Communist because art in Russia today is realistic and objective....

As I have previously stated, art is considered a weapon of communism, and the Communist doctrinaire names the artist as a soldier of the revolution... What are these isms that are the very foundation of so-called modern art?... I call the role of infamy without claim that my list is all-inclusive: Dadaism, Futurism, Constructionism, Suprematism, Cubism, Expressionism, Surrealism, and Abstractionism. All these isms are of foreign origin, and truly should have no place in American art. While not all are media of social or political protest, all are instruments and weapons of destruction....

Cubism aims to destroy by designed disorder. Futurism aims to destroy by the machine myth.... Dadaism aims to destroy by ridicule. Expressionism aims to destroy by aping the primitive and insane.... Abstractionism aims to destroy by the creation of brainstorms. Surrealism aims to destroy by denial of reason....

The artists of the “isms” change their designations as often and as readily as the Communist front organizations. Picasso, who is also a Dadaist, an Abstractionist, or a Surrealist, as unstable fancy dictates, is the hero of all the crackpots in so-called modern art.... Legér and Duchamp are now in the United States to aid in the destruction of our standards and traditions. The former has been a contributor to the Communist cause in America; the latter is now fancied by the neurotics as a surrealist....

It makes little difference where one studies the record, whether of Surrealism, Dadaism, Abstractionism, Cubism, Expressionism, or Futurism. The evidence of evil design is everywhere...

Autumn 1949: Philip Guston returns to Woodstock after a year in Italy. (DA83)

Autumn 1949: "Artists: Man and Wife" exhibition at the Sidney Janis Gallery.

The exhibition featured the work of married artist couples including Willem and Elaine de Kooning, Jackson Pollock and Lee Krasner , Jean Arp and Sophie Tauber-Arp and Ben Nicholson and Barbara Hepworth.

Gretchen T. Munsun reviewed the show for the October 1949 issue of Art News, noting "There is a tendency among some of these wives to 'tidy up' their husband's styles. Lee Krasner (Mrs. Jackson Pollock) takes her husband's paints and enamels and changes his unrestrained, sweeping lines into neat little squares and triangles."

September 4 - October 3, 1949: "The Intrasubjectives" exhibition at the Samuel M. Kootz Gallery.

In 1948 Kootz closed his gallery at 15 East 57th Street and operated out of an apartment at 470 Park Avenue. In 1949 he reopened his gallery at 600 Madison Avenue, near Fifty-seventh Street.

From Landscape with Figures by Malcolm Goldstein:

This move did not mean that he gave up Picasso or that Picasso gave up Kootz. For the first ten years of the new gallery's existence, Picasso's art was its mainstay... The move to Madison Avenue caused Kootz to rethink his position and to review the talent of his artists. Three, Browne, Holty, and Romare Bearden, were found wanting and were dismissed in 1949. Over the next six years the sculptors Ibram Lassaw and Herbert Ferber joined the gallery, but accompanying these gains were serious losses: when he put the French abstractionists George Mathieu and Pierre Soulages under contract in 1953, Motherwell and Gottlieb left. (FG241-2)

The Intrasubjectives exhibition was another attempt by an art dealer to define the new American painting by calling it "intrasubjective." (The term Intrasubjectivism had been previously used by Ortega y Gasset in the August 1949 issue of Partisan Review.) (JF135) A similar effort had been made by Howard Putzel in 1945 with his "A Problem for Critics" exhibition.

The Kootz show included work by Jackson Pollock, Adolph Gottlieb, William Baziotes, Arshile Gorky, Morris Graves, Hans Hofmann, Willem de Kooning, Robert Motherwell, Ad Reinhardt, Mark Rothko, Mark Tobey and Bradley Walker Tomlin. (PP323)

The catalogue for the show was decorated with drawings by Adolph Gottlieb and contained statements by Harold Rosenberg and Kootz.

Samuel Kootz [from the exhibition catalogue]:

The past decade in America has been a period of great creative activity in painting. Only now has there been a concerted effort to abandon the tyranny of the object and the sickness of naturalism and to enter within consciousness.

We have had many fine artists who have been able to arrive at Abstraction through Cubism: Marin, Stuart Davis, Demuth, among others. They have been the pioneers in a revolt from the American tradition of Nationalism and of subservience to the object. Theirs has, in the main, been an objective art, as differentiated from the new painters' inwardness.

The intrasubjective artists invents from personal experience, creates from the internal world rather than an external one..." (JF135)

Harold Rosenberg [from the exhibition catalogue]:

Space or nothingness... that is what the modern painter begins by copying. Instead of mountains, copses, nudes, nudes, etc., it is his space that speaks to him, quivers, turns green or yellow with bile, gives him a sense of sport, of sign language, of the absolute.

When the spectator recognizes that nothingness [is] copied by the modern painter, the latter's work becomes just as intelligible as the earlier painting. (FG242)

October 4 - 22, 1949: Robert Motherwell solo exhibition at the Samuel M. Kootz Gallery. (MR135)

c. November/December 1949: Philip Guston and Bradley Walker Tomlin rent a loft in New York.

The loft was located at University Place between 12th and 13th Street. They divided the space into two studios with Franz Kline building a partition out of two by fours and plasterboard. Guston had met Kline previously at the Cedar Street Tavern and heard that he had tools and did carpentry. (FK178/85) A few weeks later, Tomlin moved to a separate loft and Guston moved into 51 West 10th Street which would be his studio for several years. Guston's family initially remained in Woodstock and he'd commute between the two locations until they eventually joined him, moving into a small apartment together in the same building his studio was located in. They lived between Woodstock and Manhattan. His daughter later recalled that "during most of my childhood, my parents had two groups of friends: those who lived in Woodstock - year round or, as we did some years, late spring to early fall - and those who lived in New York City. (DA83/MM48-49)

Musa Mayer [Guston's daughter]:

Philip easily found another studio on 10th Street, but it was some time, a difficult year of regaining bearings, before we settled. For some months, we stayed in Robert and Becky Phelps' tiny flat on Bedford Street and then at the Albert Hotel... That was the year we began shuttling between New York City and Woodstock...

Built in the late 1850s, 51 West 10th Street, where we lived for several years, had a venerable history. The Studio Building, designed by Richard Morris Hunt, was the first building of artists' studios in New York City... We were among the last of its tenants, for it was demolished in 1954. Our apartment there was a small one-room cold water flat with high, slanted ceilings and a skylight. The toilet was down the hall, and the area where I slept was separated from the rest of the room by a tall bookcase. My father's studio was in the same building. (MM49)

Eventually the family would move into the top two floors of a building on 18th Street, between Irving Place and what was then Fourth Avenue. The living quarters, previously occupied by Harry Holtzman, were on the third floor and Guston's studio was on the top floor. It had previously been the study of the artist Walt Kuhn. (MM90-91) (Kuhn, who had helped organize the Armory Show of 1913, had been committed to Bellevue Hospital for mental problems in late Autumn 1948 and died of an perforated ulcer in a White Plains hospital on July 13, 1949.)

In 1959 Guston would move his studio to a loft over a firehouse on West 20th Street. (DA88)

November 18, 1949: Mark Rothko speaks as part of "Studio 35" series. (RO263)

Rothko spoke on "My Point of View." Admission was 59 cents. (RO611fn82)

1949: John Cage lectures about sand painting at The Club.

When in 1966, art writer Irving Sandler asked Cage whether he had alluded to Jackson Pollock, "who had been inspired by Indian sand painting" during his talk, Cage replied "No, I was promoting the notion of impermanent art, [and Pollock's] work had a permanence. I was fighting at that point the notion of art itself as something which we preserve." (IS256)

November 21, 1949 - December 10, 1949: Jackson Pollock's third solo show at Betty Parson's Gallery takes place.

Jackson Pollock's first show since the Life magazine article attracted both buyers and favourable press reaction. Pollock had only sold one painting during his previous 1948 exhibition at the gallery. This time he sold 18 of the 27 paintings exhibited. (DK292) Jackson's mother Stella wrote to her son Frank in December that it was "the best show he has ever had and sold well eighteen paintings and prospects of others they both are fine he is still on the wagon." (JP198) Buyers included Valentine Macy, Harold Rosenberg and Mrs. John D. Rockefeller III. (JP198)

The paintings again had numerical titles. To differentiate newly created paintings from ones which hadn't sold at the 1948 exhibition, Betty Parsons added the letter "A" to the previously unsold works (ie Number 1, 1948 became Number 1A, 1948." (PP323) Also on exhibit was Peter Blake's model for an "ideal museum" which featured small wire and plaster sculptures by Pollock. Blake asked the Hungarian architect Marcel Breuer to attend the show. Breuer was designing a house for Mr. and Mrs. Bertram Geller in Lawrence, Long Island. As a result of the visit he got the Gellers to commission Pollock to do a mural for their home. (PP324)

Pollock stayed in New York during the exhibit - and afterwards. Artist-collector Alfonso Ossorio let Jackson and Lee stay in a remodeled carriage house he owned at 9 MacDougal Alley in Greenwich Village. Arriving on Thanksgiving day they originally intended to stay for three weeks but ended up staying for three months.

Christmas 1949: Samuel Kootz sells Christmas gifts.

Kootz' advertising for Christmas offered framed watercolours or gouaches for as low as $100.00. Kootz' Christmas advertising read as follows: "For an unusual Christmas gift for yourself or friends... Give a framed modern water colour or gouache by an important American artist. For $100, 150, 200 as you may prefer, you may send a gift certificate to your friends entitling them to a selection from the work of the following artists: William Baziotes, Byron Browne, Adolf Gottlieb, Hans Hofmann, Carl Holty, Robert Motherwell, or we shall be delighted to make the choice for you and enclose your card with your gift." (SG232 fn80).

December 16, 1949 - February 5, 1950: Jackson Pollock exhibits Number 14, 1949 in the Whitney Annual. (PP324)

Jackson Pollock, still maintaining his sobriety, attended the Whitney reception with his wife Lee Krasner. (JP199)

End 1949: The Club has a party.

Charter members contributed collages for decoration which covered most of the walls and ceiling. This was followed by a New Years Eve party which lasted for three days. During the New Years Eve celebrations, Philip Pavia announced, "This is the beginning of the next half century. The first half of the century belonged to Paris. The next half century will be ours." (DK292)

Sculptor James Rosati [Club member]:

The first New Years party party consisted of myself, de Kooning, Kline, Lewitin, Cavallon and Ludwig Sander. A fire was lit and we decorated the place with Christmas stuff we found on the street. Each of us had a section of wall, and we created a tremendous collage made up of junk materials. It was a beautiful thing. We all bought bottles of booze and stayed up all night. It was one of the warmest evenings in my memory. We repeated it the next year. (IS31)