Abstract Expressionism 1944

by Gary Comenas (2009, Updated 2016)

1940s: Artists hang out at the Waldorf Cafeteria.

According to art writer, Irving Sandler, the Waldorf Cafeteria (not to be confused with the hotel of the same name) became the "favorite hangout for downtown painters and sculptors" during World War II. Artists continued to gather there after the war although the Cedar Street Tavern would replace it as the main hangout during the late 1940s and 1950s. Ludwig Sander recalled that when he returned from active service he rushed to the Waldorf to catch up with all the artists he had known before his military service.

Irving Sandler:

During World War II, the Waldorf Cafeteria on Sixth Avenue off Eighth Street became the favorite hangout for downtown painters and sculptors. However, they were not comfortable there; when the weather permitted, they assembled in nearby Washington Square Park. The cafeteria was a gloomy and cruddy place, full of Greenwich Village bums, delinquents, and cops. The management did not want the artists; they just drank coffee, and were often too poor to buy even a cup. What was worse, since hot water was free, some artists would bring their own tea bags, or use the ketchup on the tables to concoct tomato soup. To harass them, the Waldorf managers allowed only four persons to sit at a table, forbade smoking and, for a time, even locked the toilet. In reaction, the artists began to frequent the Cedar and to think about forming their own club." (IS23)

Philip Pavia recalled that at the Waldorf Cafeteria "we'd all sit around a big table - eight or nine of us - we'd have big discussions and big fights. We'd fight about the Surrealists and French culture. Bill de Kooning talked about his Picasso, and Gorky talked about his Picasso." (BA341)

Philip Pavia:

... there was a real hunger. We all sought each other's company and it was practically daily; six out of seven nights of the week we all sat around and talked... Droves of artists started coming into the cafeteria. Jack Tworkov, Milton Resnick - I can't name them all. Pretty soon we couldn't fit around the table. So we had about four tables. Sidney Janis would come in, and Kiesler. And John Graham would come in with complete contempt for all of us. He hated the cigarette smoke and he would hold his nose while he talked to us. Now this was the beginning of everything. (DK217)

c. January 1944: André Breton meets Elisa Claro (née Binhoff).

According to Martica Sawin in Surrealism in Exile and the Beginning of the New York School Breton met Elisa in January when "in the midst of a snowstorm, he had stopped for lunch at a favorite refugee hangout, Chez Larre, and had noticed a woman with an overwhelming sadness on her face. He subsequently learned that her eleven-year-old daughter had drowned the previous summer while at a camp in Cape Cod and that she herself had attempted suicide." (SS355)

[Note Sawin refers to Elisa Claro as Elisa "Varo." According to Hayden Herrera in Arshile Gorky: His Life and Work Claro and Breton met in December 1943. (HH431)]

Elisa (like Matta) was Chilean. Breton would marry her in July 1945 after he divorced Jacqueline Lamba. Lamba, meanwhile, had fallen in love with VVV editor David Hare. (HH431)

1944: The Museum of Modern Art purchases Robert Motherwell's Pancho Villa, Dead and Alive. (HM)

1944-45: Adolph Gottlieb serves as President of the Federation of Modern Painters and Sculptors.

During 1942 - 1943 Gottlieb had been one of the Federation's vice-presidents. In 1944 he was also awarded first prize at the Brooklyn Society of Artists Annual Exhibition.

(AG23/42)

c. Early 1944: Jackson Pollock paints a mural for Peggy Guggenheim who later spreads a rumour that he urinated in her fireplace on the day of its installation.

Although Jackson Pollock wrote to his brother on January 15, 1944 that he had "painted quite a large painting for Miss Guggenheim's house during the summer," a friend of Lee Krasner, John Little, remembered it differently. Little stopped by Pollock's studio in January and was told by Lee that "Jackson's supposed to deliver that mural tomorrow" and "he hasn't even started it." The next day Little stopped by the studio again and was told by Lee, "you won't believe what happened. Jackson finished the painting last night." (JP143/(PP329fn17))

Guggenheim was working in her gallery at the time but sent a truck to collect the mural and deliver it to her home. Marcel Duchamp and David Hare were given the task of installing the work. They quickly realized that it was too big for the space designated by Peggy. Duchamp asked Pollock if he would mind if they cut eight inches off the end of the mural and Pollock told them to go ahead. (JP144)

While it was being hung Pollock helped himself to Peggy's supply of alcohol and it was during that afternoon that he allegedly urinated in Guggenheim's fireplace, at least according to Guggenheim's memoirs. Peggy recalled that Jackson kept on ringing her at the gallery to try and get her to come and look at the mural but she told him that she had to remain at the gallery. At one point, according to Guggenheim, he walked into a party being given by her roommate, Jean Connolly, took off his clothes and drunkenly urinated in the fireplace - an event which nobody else recalled witnessing. (JP144)

1944: Peggy Guggenheim introduces Mark Rothko to Betty Parsons. (RO231)

1944: Barnett Newman draws.

Newman's early drawings relate to his interest in ornithology and botany.

1944: Barnett Newman meets Betty Parsons.

Barnett Newman, who became Betty Parsons' "close friend and advisor" (RO231) first met Parsons at a dinner party given by Adolph and Esther Gottlieb around the same time that Rothko met Parsons through Peggy Guggenheim. (RO231)

1944: Clement Greenberg becomes the art critic for The Nation. (DK221)

1944: Barnett Newman gets published.

Newman's essay "The Modern Painter's World" was published in Dyn magazine and "Painter's Objects" in Partisan Review. (SG79)

February 1, 1944: Piet Mondrian dies in New York.

Dutch-born Mondrian, one of the founders of the De Stijl group, had arrived in New York in October 1940 (via London where he had traveled to in 1938). Once in the U.S. he joined the American Abstract Artists and had his first solo show at the Valentine Dudensing Gallery in New York in 1942. He died of pneumonia on February 1, 1944 and was buried at the Cypress Hills Cemetery, Brooklyn, NY.

c. Early 1944: Arshile Gorky meets André Breton. (MS266)

According to Martica Sawin in Surrealism in Exile and the Beginning of the New York School, "Following his summer in Virginia in 1943, Gorky returned to his Union Square studio in New York, and it was probably during the winter of 1943 - 44 that he accompanied Noguchi to the dinner at the home of Jeanne Reynal where he was introduced to Breton. His meeting with Breton can have been no later than the winter of 1943 - 1944, since Breton describes a gesture made by the daughter of 'my friend Arshile Gorky' in Arcane 17 which was written in the summer of 1944. " (SS331) According to Gorky biographer, Hayden Herrera in Arshile Gorky: His Life and Work, it was "early 1944" when the two artists met. (HH430)

Gorky met Breton through the efforts of Jeanne Reynal and Isamu Noguchi. Although there are various accounts of their meeting, Gorky's wife Agnes later confirmed that they first met at a meal at the Lafayette Hotel. (BA259) Agnes, who could speak French, acted as translator between Gorky and Breton.

According to Gorky biographer, Nouritza Matossian in Black Angel: The Life of Arshile Gorky, the meeting came about after Jeanne Reynal asked Noguchi to arrange a dinner at the Lafayette Hotel with Breton and the Gorkys so that Reynal, herself, could meet Breton. (BA352) However, in a letter from Reynal to Agnes Gorky dated February 27, 1942 Reynal described Breton as "one of the most sensuel people I have ever met" which means that she actually met Breton about two years before the meal at the Lafayette. (BA352/BA529n2)

According to another of Gorky's biographers, Matthew Spender in From a High Place: A Life of Arshile Gorky, it was over lunch at the Lafayette rather than dinner that the meeting took place. The meal went well and Gorky invited Breton to supper at his studio the following week. (MS266) Breton was impressed by Gorky's work and immediately asked to have it photographed for VVV.

Anne Matta:

Breton felt very close to Gorky. He visited him a lot, appreciated him and helped him find his way. Breton had a wonderful way of inventing artists. He saw things in their work and he made suggestions to the artists that became a reality for them. (BA353)

Isamu Noguchi would later say of Breton and Gorky, "I would say that Breton himself changed his category of Surrealism to include Arshile. If Breton said he was a Surrealist, he was a Surrealist." (BA371)

February 1944: Last issue of André Breton's VVV magazine.

Matta did the (vagina dentata) cover and much of the text was written in French. (SS346) The issue included poems by a seventeen year old high school student, Philip Lamantia. (SS346)

1944: Last issue of Dyn magazine. (SS346)

February 1944: "Interview with Jackson Pollock" by Robert Motherwell appears in Art and Architecture.

According to the chronology published by The Museum of Modern Art in Jackson Pollock, the article appeared in the February 1944 issue of the magazine. (PP320) According to Martica Sawin in Surrealism in Exile and the Beginning of the New York School, the article appeared in the February 1945 issue of Art and Architecture. (SS436fn4)

The article featured reproductions of The Guardians of the Secret and Search for a Symbol although both pictures where reversed in the repros. In the article, Jackson is quoted as rejecting "the idea of an isolated American painting" and saying "I don't see why the problems of modern painting can't be solved as well here as elsewhere." (PP320) Robert Motherwell later claimed to have helped Pollock with his statement for the magazine. According to Martica Sawin, Motherwell told her in November 1985 that he, Motherwell, had actually written the statement. (SS436n5)

Robert Motherwell [quoted in Jackson Pollock]:

Pollock first began to talk a lot to me when he was asked, a year or two after I met him, by a California art magazine to produce a statement of his views. He obviously wanted to accept, but was shy about his lack of literary ability, like a diffident but proud Scots farmer. We finally hit on the scheme of my asking him leading questions, writing down his replies, and then deleting my questions, so that it appeared like a straight statement - though there is a brief passage in it on art and the unconscious that does come from me, with Pollock's acquiescence. (PP81n65)

Jackson Pollock [from the Arts and Architecture article]:

I accept the fact that the important painting of the last one hundred years was done in France. American painters have generally missed the point of modern painting from beginning to end. Thus the fact that good European moderns are now here is very important, for they bring with them an understanding of the problems of modern painting. I am particularly impressed with the concept of the source of art being the unconscious.The idea of an isolated American painting, so popular in this country during the thirties, seems absurd to me, just as the idea of creating a purely American mathematics or physics would seem absurd... The basic problems of contemporary painting are independent of any one country. (SG175/SS)

February 1944: Robert Motherwell's review of Jackson Pollock's show at Art of This Century appears in Partisan Review.

Motherwell wrote that Jackson was one out of "no more than five out of a whole generation" who "represent a younger generation's artistic chances." (JP145-6)

February 1, 1944: Edith Sachar divorces Mark Rothko. (RO204)

In order to get a divorce one had to show cause such as adultery. Edith alleged that Rothko had committed adultery in a Washington Place rooming house. (At the time Edith was living at 71 Washington Square, with her business located at 36 East 21st Street.) (RO203)

Lou Harris, an old friend of Rothko testified during the divorce hearing that he was having a drink with Rothko on September 12 and Rothko asked him to leave because he was expecting someone. Harris rang Edith and met her and Benjamin Shaw, a book dealer, in a cafeteria in the Village and the three of them then went to Rothko's room. When Rothko opened the door he was allegedly in a bathrobe with a naked woman in his bed.

The hearing didn't go smoothly. The judge berated Harris ("...you, a friend, go and tell his wife - is that part of your profession as an artist to do such things?") and wondered what his motive might be for testifying against his friend ("Are you getting paid for it by any chance?") - but the divorce was granted. (RO204)

The artist Jack Kufeld, a friend of both Rothko and his wife, would remain friends with Edith (and her second husband, an engineer) until she died in 1981.

Jack Kufeld:

Edith was not very happy with Mark because Mark was kind of an artistic slob, a very sloppy guy; and she couldn't take that... I really don't know whether she wanted so much security as she wanted him to be ambitious in other directions I suspect. She was always ambitious. She set up a jewelry factory. You know, in those days people used to make rings out of copper and silver, and that's what she went into. And Mark just had a job, sort of a part-time job, as Adolph Gottlieb did and Lou Harris did, but they called it part-time. But he used to come to help her and I don't think she was very pleased with the kind of help that he gave her. In any case, that's the way she was oriented. Her family is pretty well off, as a matter of fact. They have apartment houses in Brooklyn and quite a bit of money. So she didn't have to worry about it, but nevertheless she wanted him to be ambitious. It was very amusing that she always referred to him as - after the divorce - Rothko, as if he was a complete stranger. (JK)

February 7 - 19, 1944: "Adolph Gottlieb Drawings" at the Wakefield Gallery, New York.

Barnett Newman wrote the text for the catalogue. (AG173)

February 8, 1944 - March 12, 1944: "Abstract and Surrealist Art in the United States" at the Cincinnati Art Museum.

Organized by the San Francisco Museum of Art, with works selected by Sidney Janis, the exhibition traveled to the Denver Art Museum (26 March-23 April) after its run in Cincinnati and then to the Seattle Art Museum (7 May-10 June), the Santa Barbara Museum of Art (June-July), the San Francisco Museum of Art (July) and the Mortimer Brandt Gallery in New York in November 1944. (DK207-8/BA353)

The exhibition included work by Arshile Gorky, Jackson Pollock, Hans Hofmann and Willem de Kooning among others, in connection with the publication of Janis' book, Abstract and Surrealist Art in America, which was published in November when the exhibition was at the Mortimer Brandt Gallery. (DK207)

February 1944: Adolph Gottlieb exhibits at the Wakefield Gallery.

Barnett Newman wrote the foreword for the catalogue of a show of Gottlieb's drawings at the gallery, still run by Betty Parsons. (MH)

March 7 - 31, 1944: "First Exhibition: Hans Hofmann," at the Art of This Century Gallery.

March 1944: Matta leaves Julien Levy for Pierre Matisse. (BA370)

April 1944: Arshile Gorky works on The Liver is the Cock's Comb.

Arshile Gorky promised to give Jean Hebbeln the painting, The Liver is the Cock's Comb (1944), as a gesture of thanks for money she had given Gorky and his wife earlier. According to art dealer Sidney Janis, the painting was once referred to by André Breton as "the most important picture done in America at that time." (BA352)

From Arshile Gorky: His LIfe and Work by Hayden Herrera:

On April 20, 1944 Mougouch [Gorky's wife's nickname] wrote to Jeanne [Reynal] that Gorky had been working very hard on Liver, which she called 'that huge canvas that you saw in the storeroom'... She [Jeanne Reynal] wished she could buy the painting, but Gorky had already promised it to Jean Hebbeln, a young Sarah Lawrence graduate who, with her husband, the architect Henry Hebbeln, had been introduced to Gorky and Mougouch by the Chermayeffs.

The circumstances that led to Jean Hebbeln's acquisition of The Liver Is the Cock's Comb tells us something about the painting's euphoric color and dancelike movement and the masterful way in which Gorky composed all its notes into one splendid, pulsing harmony. Knowing that Mougouch had no money to buy clothes, Jean took her to Bonwit Teller to buy a fur coat. Mougouch asked Jean if she could have the money instead. 'When I came home with a thousand dollars Gorky couldn't believe it. Our happiness absolutely exploded and then Gorky went and started to paint The Liver Is the Cock's Comb as a result of that gift of Jean's, which went boom like that, for no reason, nothing. It wasn't an exchange for a painting, nothing. He was so full of relief. I can't tell you what it is like to always be at the end of your tether. And when Gorky was doing this painting, he said, 'Give it to Jean.' And he gave it to her.'" (HH437-8)

The painting was one of the works included in Sidney Janis' book, Abstract and Surrealist Art in America, which was published when a traveling exhibition of the same name reached the Mortimer Brandt Gallery in November 1944. Janis thought Gorky should rename the work Improvisation but Gorky insisted on the Surrealist title The Liver is the Cock's Comb and contributed a similarly Surrealist artist's statement in regard to the painting:

The song of the cardinal,

liver,

mirrors that have not caught reflection,

the agressively heraldic branches,

the saliva of the hungry man

whose face is painted with white chalk.

According to Gorky biographer, Nouritza Matossian "'My liver' is an Armenian term of endearment. The cockscomb, or crown, denotes masculine pride... The cockerel was a symbol of manhood, in some villages beheaded with a single stroke of the knife by the bridegroom to prove he was not 'lily-livered.' It has been suggested that in his text Gorky cribbed Surrealist poetry from View, as he had done from Eluard or the letters of Gaudier Brzeska. (BA354)

April 1944: "Five American Painters" appears in Harper's Bazaar.

The article by James Johnson Sweeney was a double page spread featuring Milton Avery, Morris Graves, Roberto Matta, Jackson Pollock and Arshile Gorky. (BA355)

When Gorky showed his work to Sweeney he mentioned that he had been drawing close-up from nature in Virginia and Sweeney used this in his article: "Arshile Gorky's latest work shows his realisation of the value of literally returning to earth. Last summer Gorky decided to 'look into the grass' as he put it. The product was a series of monumentally drawn details of what one might see in the heavy August grass." (BA355)

A large color reproduction of Jackson Pollock's, The She-Wolf was reproduced in the article and purchased about a month later by Alfred Barr for The Museum of Modern Art. (SG87)

May 2, 1944: Peggy Guggenheim notifies Jackson Pollock that the Museum of Modern Art purchased The She-Wolf.

James Johnson Sweeney who belonged to the acquisitions committee of MoMA recommended the painting to Alfred Barr who was at the time the Director of Research in the Department of Painting and Sculpture. James Thrall Soby, then the Chairman of the museum's Department of Painting and Sculpture, also recommended purchasing the work as did Sidney Janis who was head of the museum's acquisitions committee. (PP320)

Barr was interested but felt the $650 asking price was too high. The museum asked Peggy Guggenheim if she would sell it for $450. She refused. After Johnson's article, "Five American Painters" appeared in Harpers Bazaar, with a large color reproduction of the work, the museum reconsidered their offer and bought the painting. (PP320) Pollock received a telegram from Guggenheim on May 2, 1944 telling him "Very happy to announce the museum bought She Wolf for $600 today. Love Peggy Guggenheim." It was the first work that Pollock sold to a museum. Pollock wrote to his brother Charles after the purchase, "I am getting $150 a month from the gallery, which just about doesn't meet the bills." He added "I will have to sell a lot of work thru the year to get it above $150. The Museum of Modern Art bought the painting reproduced in Harpers this week which I hope will stimulate further sales." (JP146)

Spring 1944: Arshile Gorky returns to Virginia. (BA355)

Arshile Gorky and his wife Mougouch (Agnes Magruder) stayed at Agnes' parents' farm, Crooked Run. Agnes was in the early stages of her second pregnancy. (BA362) She would have a miscarriage at the beginning of autumn when her and Gorky were still at the farm. (BA363)

Gorky took his giant easel (his "Golgotha") with him to Virginia in order to work on large paintings. During his stay at the farm he had produced thirty paintings, including How My Mother's Apron Unfolds in My Life, They Will take My Island and One Year the Milkweed. (BA369)

While staying at the farm Gorky and Mougouch subleased their New York studio. In a letter from Mougouch to Jeanne Reynal in April, Gorky's wife noted that they would be leaving soon for Virginia and that Margaret Osborn was going to sublease their Union Square studio. In another letter, dated May 5th, she told Reynal that she had visited Matta in his studio ("on the lure he would give me [Breton's novel] Nadja - which he did") and that Matta had shown her some os his erotic drawings ("He becomes more & more like a spoiled boy who wants to masquerade as de Sade.") She also mentioned a dinner with André Breton.

Agnes ("Mougouch") [from the letter to Jeanne Reynal, May 5, 1944]:

O what a beautiful man [Breton]. I called him to say goodbye & he wanted to come so we had a huge seigniorial steak as planned with you & then we all felt so happy we forgot to eat a specially good cheese I bought for HIM. We just talked quietly - he looked again at G.'s drawing with the idea of choosing one or two to be reproduced in color in the next VVV... Gorky's huge new canvas [The Liver Is the Cock's Comb] was in the room & Breton was v. impressed with it & spoke of it with great feeling & emotion... Then we talked of the country & little brooks & G. & he swapped stories via me about stones & walnuts & smells & Arshile was in a very poetic mood, & Breton sensed that & really felt love for him I think. We spoke of sadness & why & breton confessed his everlasting sadness & told of how in his happiest moments with women even they would say but you are sad & he would say no yet know that it was true. Gorky shares this with him though he is wilder than B. and you know Jeanne at this moment we all had tears in our eyes. It was a very beautiful evening & very rare. (HH441-2/original grammar retained)

(Although she mentions that Breton was interested in Gorky's drawings for VVV, the last issue of the magazine had already been published. It's possible that Breton was planning another issue which never came to fruition.)

While staying at the farm, Gorky's wife immersed herself in reading Breton with Gorky joking that she had lost her head over the Surrealists. (BA359) She wrote to Breton but received no response - he had gone to Canada (where he would begin writing Arcane 17) for three months with his new love, Elisa Claro. (BA362)

Also at Crooked Run farm was Agnes' mother, her mother's housekeeper and cook and Agnes' sister Esther.

Esther Magruder:

He [Arshile Gorky] never wore shoes, neither did she [Agnes], and they stripped naked at the drop of a hat. He loved gardening. He had a vegetable garden. The cows got into it, very early one morning. I heard the cows eating. I was out there, Gorky and Aggie were stark naked, trying to chase them out. (BA360)

Esther also recalled Gorky and her mother arguing over politics.

Esther Magruder:

Politics was a romance for Gorky. He dreamed there was ideal world out there. Someday everybody would love everybody else. He would paint and everything would be perfect. Gorky would talk politics and defend what Stalin was, and my mother went through he roof. No one avoided conflict. Almost every evening they had fights about politics. I couldn't stand all those fights. (BA360)

Locals were invited to barbecues on the farm, including the postmaster A.M. Jannings.

Esther Magruder:

Gorky told A.M. Jannings that Christ had been back to the world and he knew it for a fact because he had left a pubic hair in the whorehouse which was identifiable. I remember thinking, 'This isn't going to go down very well.' A. M. Jannings was just laid out. He was a Southern Baptist and went to church every Sunday and he was in total shock. (BA361)

"The people around here thought Gorky was the the weirdest thing they had ever seen, lying down in the field, flat, and looking up. Their idea was, if he's a painter, he sits up. Maybe he did sketches. I don't know, I never went up to him. He was concentrating. (BA361)

Gorky and Agnes returned to New York in November after almost eight months in the country. (BA368)

May 1944: Barnett Newman organizes an exhibition at the Wakefield Gallery.

The exhibition at the Wakefield, still being run by Betty Parsons, consisted of Pre-Columbian sculpture. Many of the pieces were from the American Museum of Natural History. During the weekends when Parsons was in the country, Barnett and his wife looked after the gallery. (MH)

Late March - April 25, 1944: National Academy's 118th Annual Exhibition.

Franz Kline won the S.J. Wallace Truman Prize for the second year in a row - this time for Lehigh River, Winter.

(FK177/Edward Alden Jewell, "The Two Academies, Right and Left Represented in Current Annuals - Juan Gris in Retrospect," The New York Times, April 2, 1944, Section: Drama Recreation News, p. X7)

March- Early April, 1944: Eighth Annual Exhibition of the American Abstract Artists at the Mortimer Brandt Gallery at 15 E. 57th St.

Artists included Piet Mondrian, Ad Reinhardt (named as A.D.F. Reinhardt in The New York Times review), Josef Albers, Suzy Frelinghuysen, Harry Holtzman, Fritz Glarner, Ibram Lassaw, Eleanor de Laittre, Charles G. Shaw, Carl Holty, Robert Jay Wolff, A.E. Gallatin, Alice Trumball Mason and Ilya Bolotowsky.

(Edward Alden Jewell, "The Two Academies, Right and Left Represented in Current Annuals - Juan Gris in Retrospect," The New York Times, April 2, 1944, Section: Drama Recreation News, p. X7)

Spring 1944: "First Exhibition in America of Twenty Paintings" at Peggy Guggenheim's Art of the Century Gallery.

Americans were shown alongside European masters like Picasso, Braque, Léger, Mondrian and Miró. (RO208)

American artists included Mark Rothko (Entombment), Jackson Pollock (Pasiphaë), Robert Motherwell, David Hare (The Frog is a Heart) and Laurence Vail.

Spring 1944: Peggy Guggenheim renews Jackson Pollock's contract for another year. (JP147)

Spring 1944: Thomas Hart Benton visits Jackson Pollock for the last time.

Benton visited Pollock in his studio. (JP147)

c. Spring/Summer 1944: "Art in Progress: 15th Anniversary Exhibition" exhibition at The Museum of Modern Art.

The show was an eclectic mix of styles ranging from Surrealism to Social Realism. European artists included Dali, Ernst, Hayter, Tanguy, Masson, Miro and Matta (Vertige d'Eros). American artists included Peter Blume, Walter Quirt and Arshile Gorky (Garden in Sochi), Jack Levine, Philip Evergood, Milton Avery, Paul Burlin and Edward Hopper. (SS352)

Summer 1944: Howard Putzel announces his departure from Art of This Century.

Putzel left the gallery in order to start his own gallery, Gallery 67. (SS366)

Summer 1944: Barnett Newman and wife spend the summer in East Gloucester, Massachusetts.

It was the third year in a row that Newman spent the summer there. Barnett was beginning to produce art again and made a series of crayon drawings. (MH)

Mid-June 1944: Jackson Pollock and Lee Krasner rent a studio in Provincetown for the summer.

Jackson and Lee sublet their 8th Street studio and rented another one on Back Street in Provincetown. Howard Putzel, who had left Art of This Century and planned to open his own gallery, joined them for two weeks during the summer. (PP321)

Pollock and Krasner traveled to Cape Cod by train and Hans Hofmann, who Lee had studied under, met them at the station in Hyannis. On the way to Provincetown their car, driven by Hofmann, got stuck in a sand dune. Pollock managed to lift it out of the sand which left a lasting impression on Hofmann. When later asked about Pollock, he'd say "Pollock? He's strong. He lifts cars." (JP148)

Neither Lee nor Pollock completed any work that summer despite having shipped up rolls of canvas from New York. He wrote to his brother Sande and his mother Stella in Connecticut, "I've taken a crew cut and look a little like a peeled turnip - or beet. Haven't gotten into work yet... What are the chances of your coming up? Let us know and we'll work out some arrangements." (JP148)

August 1944: Jackson Pollock participates in gay "drunken sexual idylls" in Provincetown.

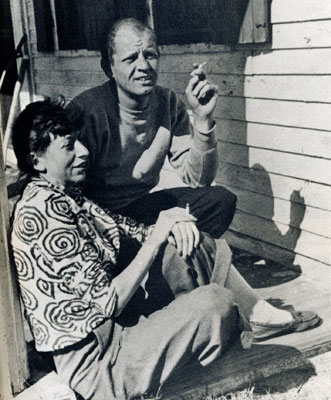

Lee Krasner and Jackson Pollock in Provincetown

(Photographer unknown)

From The Living Theatre: Art, Exile, and Outrage by John Tytell:

Frequently, during the summer, Pollock would appear at the cottage shared by Julian [Beck] and Bill Simmons in a semidrunken state. Part of the cottage was redolent of homosexuality, mostly because Simmons was self-consciously gay and eager to proselytise. Every night, a group of six to eight men would gather there to drink and talk. The balcony was reserved for sexual encounters. In August, as the weather grew warmer, Pollock would appear at any time of day or night. He had been struggling to repress homosexual inclinations for years, but on various occasions that August, whenever he felt sufficiently enraged at his wife or drunk enough to lose himself, he participated in what Julian would subsequently categorize as drunken sexual idylls. According to Julian, the sex was usually disappointing, and Pollock was too drunk to perform adequately. Several times, Lee Krasner came searching for him, and either Julian or Simmons would pretend that he was not there. For Julian, these meetings were unsatisfactory because of the sordid, forced nature and because Pollock was so evidently wrestling with obsessive problems that caused him so much pain he had to drink himself to the precipice of oblivion. Furthermore, the act they had consummated was a sort of blind groping, more lurchingly desperate than loving. (JT23)

Tytell notes that "Naifeh and Smith (Jackson Pollock, p. 249) quote Pollock's friend Peter Busa who was convinced Pollock had encounters with men. Naifeh and Smith also cite Lee Krasner who told several close friends that Pollock liked men, though the subject of homosexuality made him nervous. Naifeh and Smith (p. 480) claim that homosexuality was on his mind in the summer of 1944 and that after his opening at Peggy Guggenheim's, he frequented a gay bar called George's Tavern in the Village where he met Tennessee Williams." (JT357n.8)

The artist Harold Stevenson also claimed to have had sex with Jackson Pollock:

Harold Stevenson (20 April 1999, Long Island City):

Now to drop an ART name: Jackson Pollock I knew in the biblical sense (several times) from Mary's Bar on West 8th Street across the road from the original Whitney Museum (Greenwich Village 1949). Jackson fucked my ass not my brain. That's all I have to say... (HS13)

According to Artnet, Stevenson and Pollock would also "participate with one another" at Alfonso Ossorio's cottage in Springs, L.I. "I didn't mind going to bed with him, I just didn't want to paint like him" Stevenson is quoted as saying.

August 1944: Article by Barnett Newman on Pre-Columbian art appears in La Revista Belga.

Newman had meet Luis Jesus Navascués, the editor of the propagandist magazine La Revista Belga, at the Wakefield Gallery. Over the next two years he would write several art reviews for the magazine (and also for Ambos Mundos). (MH)

August 12 and 19, 1944: Clement Greenberg criticizes Surrealists.

From Surrealism in Exile and the Beginning of the New York School by Martica Sawin:

... he [Greenberg] launch a double-barreled attack on Surrealism in two successive numbers of The Nation (August 12 and 19). He started with a negatively charged comparison of Surrealists to the pre-Raphaelites on the basis that both sought to change the structure of industrialized society and that both attempted to reinvigorate academicism... Greenberg then sought to separate the Surrealists of whom he approved - Miro, Arp, and Masson who used automatism as a 'primary factor' - from those of whom he disapproved - Ernst, Dali, Tanguy, and Magritte who illustrated the fantastic in literal detail; "Ernst's volcanic landscapes," he wrote, "look like exceptionally well manufactured scenic postcards." The principal crime of the second group was that they were outside the "tradition of painting which runs from Manet through Impressionism, Fauvism, and Cubism [which] created the first original style since the French Revolution, and the only original one our bourgeois society has been capable of"... By setting up the Surrealists as a target he [Greenberg] could discredit the last existing avant-garde and install a legitimate heir to the modern tradition. Who that heir was to be would become evident in the reviews he wrote in the fall. (SS353)

The two essays were reprinted in England in the January 1945 issue of Horizon. (SS437n12)

August 25, 1944: Paris is liberated.

The liberation of Paris happened earlier than expected - at least for the Americans. General Eisenhower wanted to leave Paris in German hands in order to allow Patton to continue chasing the Germans across northern France and possibly push through the Rhine. Dealing with Paris would divert supplies needed elsewhere.

The liberation was largely accomplished by the generally ill-equiped citizens of the city. Military troops did not arrive until August 25th after about a week of skirmishes that started with a strike by the police force objecting to a plan by the authorities to disarm sections of the force. The strike began on Tuesday, August 15, 1944, with the police joined by metro workers. A call for "l'insurrection populaire" was published the same day in the Communist party's newspaper L'Humanité. The following day postal workers joined the strike.

On August 17th the BBC announced the occupation of Chartres, Dreux and Orléans by allied forces. The Germans ordered the evacuation of the Vichy government to Belfort, near the German border. (PL37) On August 18th posters were put up in Paris calling for an insurrection by its citizenry. On the 19th the French tricolore appeared on several public buildings including the Préfecture of Police. The German military attacked the Préfecture building without success. Their tanks were equipped with armour-piercing shells which made holes in the walls of the building but couldn't break them down. (PL39) By the 20th the National Council of the Resistance managed to take over the Hôtel de Ville. Although the Germans fired at the Hotel over the next four days they never mounted a full-scale attack, apparently unaware that inside the building the insurgents had only four machine-guns and a small number of revolvers to defend themselves with. (PL37-39)

After hearing reports of the ongoing insurrection at his base near Argentan, French General Leclerc sent a small detachment to Versailles on the evening of the 21st without permission of the Americans who continued to procrastinate about sending troops. (PL40) On the night of August 22nd a messenger finally convinced General Eisenhower's staff officers that failure to move on Paris immediately would lead to a massacre and possibly the destruction of the city. Shortly before nightfall Leclerc received an order from General Omar Bradley to advance rapidly on Paris. Leclerc's troops arrived in Paris shortly after 9:00 a.m on August 25th and at 2:15 a French tricolore was hung from the Arc de Triomphe by Parisian firemen. (PL52) A formal act of surrender was signed and de Gaulle arrived at the Gare Montparnasse at 4:15 p.m. After being received at the Hôtel de Ville in the evening, he delivered a short but rousing speech in both French and English to the people of Paris. On the 29th the Americans arrived and on the 31st the seat of the French Provisional government was transferred to Paris.

Although the street battles with the Germans during the insurrection had produced a considerable amount of Parisian causalities, the cultural landmarks of the city survived largely intact.

From Paris After the Liberation 1944-1949: Revised Edition by Antony Beevor and Artemis Cooper:

Paris being Paris, cultural landmarks counted for a much as ministries and police headquarters when it came to revolution. For the acting profession, the first place to be liberated (not that there were any Germans there) was the Comedie-Francaise. Yves Montand, who had recently established himself in Paris as a singer, appeared for sentry duty; an actress had rung Edith Piaf, his lover and mentor for the last two weeks, to say that they needed more volunteers. The twenty-three-year old Montand gave the secret knock to gain admittance to Moliere's theatre.

Actors and actresses greeted each other as if this was the greatest first-night party of their lives. Julien Berthau, appointing himself their leader, made a rousing speech, ending with the cry of the moment: 'Paris sera liberé par les Parisiens!' The whole company in a surge of emotion sang the forbidden Marseillaise, standing to attention. But there was something of an anti-climax when Berthau gave the order to distribute weapons. A few hundred metres from where they stood, German tanks waited for the first sign of trouble. To oppose them the Comedie-Francaise could produce just four shotguns and two stage revolvers. (PL42-43)

The "insurgents" at the Comedie Francaise remained unharmed but other Parisian insurgents weren't so lucky. The records of the Ville de Paris show that 2,873 inhabitants were killed during the month of August. (PL58) The largest single group of war-time causalities during the occupation of Paris was the city's Jewish population. On July 2nd 1942, René Bousquet, the Vichy prefect of police, began putting into operation a planned deportation of Parisian Jews to Germany. On the night of July 16, 1942 approximately 13,000 Jews, including 4,000 children, were rounded up and transported to the Velodrome d'Hiver stadium. Over a hundred committed suicide and most of the rest later died in German concentration camps. (PL14)

After the liberation French citizens suspected of collaborating with the Germans were attacked on the streets. Some women who had slept with the enemy were subjected to having their heads shaved by angry crowds which made them easily identified as collaborators.

From Paris After the Liberation 1944-1949: Revised Edition by Antony Beevor and Artemis Cooper:

Some women were subject to even greater degradation. There are photographs of women stripped naked, tarred with swastikas, forced to give Nazi salutes, then paraded in the streets to be abused, with their illegitimate child in their arms. There are also reports in some areas of women tortured, even killed, during these barbaric rites. In the 18th arrondissement, a working-class area, a prostitute who had served German clients was kicked to death...

A number of Resistance leaders tried to stop head-shaving. The Communist military commander, Colonel Rol-Tanguy, had posters run off and pasted up which warned of reprisals against any further incidents. Another leader, René Porte, respected in his quartier not least for his strength, bashed the heads together of a group of youths he found shaving a woman's head. One woman is said to have shouted at her shearers, "My ass is international, but my heart is French." (PL88-9)

Autumn 1944: Jackson Pollock makes prints at Atelier 17.

Stanley William Hayter's Atelier 17 was located across the street from Pollock and Krasner's apartment. (PP321) Hayter's workshop was popular with the Surrealists. Hayter encouraged experimentation and used the Surrealist technique of "automatism" to produce abstract engravings.

Jackson Pollock's friend (and ex-high school classmate) Reuben Kadish later commented that he had "inveigled" Jackson into attending Hayter's workshop: "I inveigled Jackson into trying it because I thought his work had a kinship to Hayter's prints." (JP149) (In the January 15, 1942 issue of Art News a critic with the initials J.W.L. had written that Jackson Pollock's "whirling figures" resembled work by Hayter.) Kadish had been an assistant to Hayter and had a key to the loft so he and Jackson would work there when nobody else was around. (SS370)

Reuben Kadish:

Pollock did not like working in the shop nor was he carried away by etching. The plates were never editioned during his lifetime and they began to exist only after his death. (SS70)

Eleven engravings done by Pollock at Atelier 17 were found by Lee Krasner after his death. Reuben Kadish recalled that "He wasn't happy with the prints."

It wasn't Pollock's first attempt at printmaking. When he was on the Federal Art Project he sometimes visited Theodore Wahl's printing workshop. Wahl later commented that "Jackson wasn't very serious" about printmaking. "He'd come up and say, 'I want to do a lithograph.' I'd flip him a stone, and he'd make a lithograph. He'd come back six weeks later, and it was the same thing. The problem with Jackson and printmaking is that you have to stick to the medium in printmaking - it's very technical - and Jackson couldn't stick to the medium." (JP150) One day Wahl left Jackson alone in the workshop and he helped himself to some tubes of oil paint and when Wahl returned was using the tabletop as his canvas. Wahl threw him out of the workshop. (JP151) According to Martica Sawin, "numbers 4, 6, 7 and 10 [of the Pollock prints] are the first of his works in which the entire surface is used in an allover manner. Since they were unfinished, they also provide, if one looks closely, a clue to the way the initial image is absorbed into and obliterated by the linear flow." (SS70)

c. Summer - October 1944: André Breton stays in Canada.

Breton stayed in an isolated cabin on Canada's Gaspé Peninsula with Elisa Claro. (SS355) While there he worked on Arcane 17.

Autumn 1944: Lee Krasner persuades Jackson Pollock to visit her homeopathic doctor Elizabeth Wright Hubbard. (PP321)

Pollock continued to drink and had stopped seeing his previous analyst, Violet de Laszlo in 1942. Janet Chase, a student of Hans Hofmann, later recalled an incident that occurred when she accompanied Hofmann to Jackson's apartment. As they were walking up the stairs to his apartment, a painter's easel came tumbling down the staircase. Hofmann picked it up and carried it back to the apartment . When he gave it back Hofmann asked why he had thrown it down the stairs and Jackson started to cry saying "I hate my easel. I hate art." (JP144)

Pollock felt comfortable with Hubbard, and would often stop by her office to talk to her. If she was busy she would ask him to wait in her apartment upstairs from her office. Hubbard's daughter later recalled that "He'd just sit there with his head in his hands." (JP145)

End October - November 11, 1944: First solo exhibition of work by Robert Motherwell at Peggy Guggenheim's Art of This Century gallery. (SS359/MD276/MR)

The exhibition included paintings, drawings and papiers collés. (MD276) The preface to the catalogue was written by James Johnson Sweeney. (MR135) In 1982 Motherwell would say, "I moved away from Surrealism around 1944 almost as quickly as I moved into it." (SS346)

From Surrealism in Exile and the Beginning of the New York School by Martica Sawin:

Motherwell's first one-man show followed at the end of October. It was heavily Mexican and/or Spanish in theme, including such works as Zapata Imprisoned and The Little Spanish Prison; Maria Motherwell's father had been a general in the time of Pancho Villa, so the artist had heard direct accounts of the revolution. His collage, Pancho Villa Dead and Alive, done in 1943 after Matta had advised him to work larger, was inspired by a photograph of Pancho Villa after he had been shot from Anita Brenner's book The Wind That Swept Mexico; it was purchased in the year it was made by the Museum of Modern Art. In addition, the tragic outcome of the Spanish Civil War already loomed large as a subject that would recur in this work for decades. (SS359)

1944: The first book edited by Robert Motherwell of The Documents of Modern Art series is published.

There would eventually be 14 books published in the series.

Robert Motherwell:

Well, all my life next to paintings I like books the best and always or for many years, decades, have haunted bookshops, secondhand bookshops, any kind of bookshops looking for things that interested me... And when I have attacks of anxiety, which I do all the time - as all artists do - one of the ways I alleviate it is to go to a bookshop and browse. In the forties the most pleasurable place to browse if you were interested in art was at Wittenborn's and Schultz's Bookshop which was on the floor above Curt Valentin's gallery - which was also the best gallery then. And I used to go in and look at things by the hour and talk to the people who came in. I'd talk to Wittenborn and Schultz and so on. Like most painters I'm a very poor linguist and I often used to be upset that there would be something in French or German or Italian that I couldn't read. One day we were talking about it and somehow out of the air came the idea that we should put all these things, or as many as we could, into English. And we just shook hands on it. Schultz was the deepest book lover of all. He insisted - and I had no reason to disagree - that Apollinaire's The Cubist Painters would be the first volume. We all agreed that all the books should be by artists themselves. Wittenborn had the feeling that they should be only in paperback. He thinks books are too expensive, with which I agree. But it was too premature. And they weren't publishers; they were small art bookstores publishing some books and it was too big a problem for them to take on by themselves...

Then Schultz was killed in a trans-atlantic plane crash. I think Wittenborn and Schultz were partners and I think Wittenborn was in the economic position that he had to pay off Schultz's estate and there was no capital left. Also Wittenborn literally and deeply believed in astrology - I believe this was in 1950 - and had my chart read by a very famous astrologer - to my diffidence - and the astrologer predicted seven terrible years for me. And I think that also affected Wittenborn's decision not to continue. And ironically the astrologer was absolutely right. That year I entered into a disastrous marriage which presently nearly paralyzed me as a painter. But during those years I was a professor at Hunter College and did very well there. And I think I would have done very well editing. But, anyway, through Schultz's unfortunate death, the wrongness of the stars, and so on, the thing came to an end. Several years ago Wittenborn came back to me and wanted to begin again. But I didn't want to be subject to astrology again so I went with Viking instead. (SR)

October 1944: The unemployment rate continues to decrease.

By October 1944 only 630,000 people were out of work. (SG90)

October 1944: Picasso joins the French Communist Party (PCF). (AI648)

His reasons were stated in an interview by Pol Gaillard published in full in the French Communist Party newspaper L'Humanité, 29-30 October 1944.

Pablo Picasso:

My membership of the Communist Party is the logical consequence of my whole life, of my whole work. For, I am proud to say, I have never considered painting as an art of simple amusement, of recreation; I have wished, by drawing and by colour, since those are my weapons, to reach ever further into an understanding of the world and of men, in order that this understanding might bring us each day an increase in liberation... these years of terrible oppression have shown me that I must fight not only through my art, but with all of myself. And so, I have come to the Communist Party without the least hesitation, since in reality I was with it all along... Is it not the Communist Party which works the hardest to know and to construct the world, to render the men of today and tomorrow clearer-headed, freer, happier? Is it not the Communists who have been the most courageous in France as in the USSR or in my own Spain?... I have always been an exile, now I am one no longer; until the time when Spain may finally receive me, the French Communist Party has opened its arms to me; there I have found all that which I most value: the greatest scholars, the greatest poets, and all those beautiful faces of Parisian insurgents which I saw during the days of August. (AI648/9)

October 3 - October 30, 1944: Kay Sage solo exhibition at the Julien Levy gallery. (MA)

October 4, 1944: William Baziotes' first solo exhibition opens at Peggy Guggenheim's gallery, Art of This Century. (SS357/359)

Baziotes' work had previously been shown at the gallery in the group Spring Salons of 1943 and 1944. (MD275) He hung the show with the help of Robert Motherwell. Baziotes was so nervous before the opening that he fainted. (MD275) Later, his wife, Ethel, recalled that Guggenheim actually preferred the work of Baziotes to Pollock. (MD275)

Maude Riley reviewed the exhibition for Art Digest, writing "If many of the canvases seem repetitive, and if some of them seem somewhat unsure, these faults are less impressive than the many virtues." (MD275) Guggenheim bought two large gouaches and one small oil painting for a total of $450.00. (MD275)

Baziotes' earlier work, such as The Butterflies of Leonardo da Vinci as exhibited in the "First Papers" exhibition in 1942, was inspired by plant and insect life whereas at least some of the later paintings in the 1944 show (i.e. The Wine Glass, The Balcony and The Parachutist) were more abstract and incorporated a grid and abstract curvilinear forms. (SS359)

Clement Greenberg reviewed the show for The Nation (November 11, 1944) noting that Baziotes "... confronts us with big, substantial art, filled with real emotion and the true sense of our time." He praised Guggenheim for "her enterprise in presenting young and unrecognized artists. Two of the abstract painters she has recently introduced, Jackson Pollock and William Baziotes... have already placed themselves among the six or seven best young painters we possess." (SS359) Greenberg added, "The future of American painting depends on what Motherwell, Baziotes, Pollock and only a comparatively few others do from now on." (SS361)

November 1944: Arshile Gorky returns to New York from Virginia. (BA369)

When André Breton saw the paintings Gorky produced in Virginia, he was impressed and promised to find Gorky a gallery and photographed one of the works for his new book, Eternal Youth. (BA369) With Breton's blessing and the acceptance of the Surrealists, Gorky suddenly became a name to be reckoned with. He was slightly baffled by all the attention, asking Jeanne Reynal if his work had really altered so much. (BA371)

November 1944: Abstract and Surrealist Art in America by Sidney Janis is published by Reynal and Hitchcock. (PP321/AG172)

The book was published in conjunction with the "Abstract and Surrealist Art in the United States" exhibition when it reached the Mortimer Brandt Gallery in New York in November after opening in Cincinnati and traveling to Denver, Seattle, Santa Barbara and San Francisco (see February above).

The "Reynal" of Reynal and Hitchcock, the publishers of the book, was Jeanne Reynal's brother. Twenty-nine artists were included as "abstract." Twenty-eight artists were included as Surrealists and fifteen artists were included in the section devoted to "American Works by Artists in Exile." Artists identified as Surrealists in the book included Adolph Gottlieb, Mark Rothko, William Baziotes, David Hare, Kamrowski, Margo, Andre Racz, Jimmy Ernst, Joseph Cornell and Dorothea Tanning. Pollock's The She Wolf and Gorky's The Liver Is the Coxcomb were both reproduced. (SS349/351)

Painters whose work was "a fusion of elements from each" of "two antithetical directions, abstraction and surrealism" included David Hare, Adolph Gottlieb, Mark Rothko and Arshile Gorky. Émigré artists included Mondrian, Léger, Chagall and the European Surrealists. Josef Albers and Hans Hofmann were included the abstract art section. (SS351)

December 20, 1944: Julien Levy becomes Arshile Gorky's dealer. (HH463)

Gorky signed his contract with Julien Levy on December 20, 1944. Levy took a one-third commission from all sales and paid Gorky a $175 advance each month in exchange for a number of drawings and paintings to be delivered later in the year. (BA374) Although Gorky had spent a considerable amount of time in Levy's gallery in previous years, it was only after Breton's endorsement of Gorky that Levy offered him a contract.

Gorky's wife Mougouch [Agnes Magruder] wrote to Jeanne Reynal about the deal on January 10, 1945:

Mougouch:

I have a strange hallucination that I have not told you of the contract with Julien Levy?????... anyway julien l. is all excited over g and feels he has felt that way ever since he knew g.s work which was 15 yrs ago... Its true you know he almost gave g. a show about 10 yrs ago... Breton... is writing the forward [sic] to the catalogue and all this with the framing and painting has made it necessary to put off the show, originally scheduled for the first week in feb... The manipulations with julien are sort of dense to me but as I understand he owns so many paintings per annum plus so many drawings and we get a monthly dispensation of $175 and then after j. has sold enough to cover his annual outlay on g. we get 2/3 on every thing sold that does not belong to him. (HH463-64/original grammar retained)

December 1944: Arcane 17 is published.

Breton's book was originally published by Brentano's in an edition of 325 with illustrations by Matta relating to Tarot cards. Some copies included an original drawing by Arshile Gorky. (SS357)

December 4 - 30, 1944: "40 American Moderns" at Howard Putzel's 67 Gallery.

The exhibition was the inaugural exhibition of Putzel's new gallery who, previously, had advised Peggy Guggenheim on her collection. Artists in Putzel's first show included Hans Hofmann, Adolph Gottlieb, Mark Rothko, Robert Motherwell, Jackson Pollock, William Baziotes, Morris Graves, Hans Hofmann, Richard Pousette-Dart and Mark Tobey. (AG42/RO600n6)