Abstract Expressionism June - December 1948

by Gary Comenas (2009, Updated 2016, 2020)

June 1, 1948: Arshile Gorky's wife has a birthday party.

Among the guests at Agnes' 27th birthday were her and Gorky's neighbours - the writer Malcolm Cowley and his wife, Yves and Kay Tanguy, Peter Blume and his wife and Alexander and Louisa Calder. (MS355) Agnes' mother arrived with Agnes' and Gorky's children, Maro and Natasha, who she had been looking after in Virginia. According to Gorky biographer Matthew Spender who later married Maro, Gorky told Agnes [nicknamed "Mougouch"] that he didn't want to see his children because it would be too painful.

Matthew Spender [from From A High Place, A Life of Arshile Gorky (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000)]:

"Essie [Agnes' mother] came up from Virginia with the children. Before they arrived, Gorky told Mougouch [Agnes] that he did not want to see the children again. The agony of saying good-bye to them when they left had been so terrible. What was the point of having them back, he said, if it only led to yet another separation, yet another painful good-bye? Life was easier without them...

The next day, before leaving, Essie took Gorky aside and tried to have a 'sensible' talk with him. Her daughter had mentioned that he had become very possessive these past few months. Was it true that she could not even do the shopping without his getting fretful? American women were used to a certain freedom; he knew that, surely. They couldn't just be locked up! Gorky listened without responding. Essie meant well, but it was the last subject about which he could ever be 'reasonable'... Essie and Mougouch privately decided that Maro and Natasha had better go back to Virginia. Essie would take them. Without the children, Gorky and Mougouch might have a better chance of working things out." (MS355-56)

Another Gorky biographer, Hayden Herrera whose father later married Gorky's wife, wrote about the same incident without mentioning that it was at Gorky's request that the children were removed.

Hayden Herrera [from Arshile Gorky: His Life and Work (London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2003)]:

"On June 1, 1948, Gorky and Mougouch gave a party to celebrate her twenty-seventh birthday. The Cowleys, Blumes, Calders, Josephsons and Tanguys were among the guests. As Mougouch danced Gorky watched with a disapproving eye. Her beauty, youth, and giddy energy were in terrible contrast to his maimed body. She was the farthest thing from the modest, compliant Armenian bride whom he had pictured only a decade or so earlier in Portrait of Myself and My Imaginary Wife. He turned to his mother-in law, who had come up from Virginia for the birthday, and complained that Mougouch was a flirt. Esther Magruder had noticed Gorky's increasing irritability and gloom as well as his possessiveness. She came to her daughter's defense: 'Well, you know, Gorky, you do keep Agnes on a very short leash. She's an American girl, born and bred, and they are used to a certain amount of independence. I think you ought to let her do a little more of whatever she wants to do.'

After the party, Mougouch and Esther decided that the children should accompany Esther home to Virginia. The atmosphere in the Glass House was too tense... Mougouch was understandably restless. Her marriage had never been sexually fulfilling; now she was finding it emotionally stifling as well. 'Gorky was isolating me from his life. He was wrapped in silence all those last months. There was no way of getting into it.' His remoteness made her long for intimacy. For years she had fended off Matta's flirtatiousness. Now his naughty-boy behavior began to attract her: Matta was accessible and playful, whereas Gorky was remote, dark, and saturnine." (HH583-4)

Nouritza Matossian, who has no Gorky family connections but (unlike Herrera and Spender) is Armenian, also did not mention that Gorky asked that his children be taken away in her biography of the artist. On the contrary, in Matossian's account the children being taken away horrified Gorky:

Nouritza Matossian [from Black Angel: A Life of Arshile Gorky (London: Chatto & Windus, 1998)]:

"Mrs. Magruder [Agnes' mother] arrived to spend Agnes's birthday with them on 1 June, alarmed by their unhappiness. She tried to reason with Gorky. 'You know you do keep her on a very tight rein for an American girl. She's used to having a certain freedom that I have.'

Mrs. Magruder tried to give the couple a break by taking the children away. This terrified Gorky, who told Muriel Levy that his 'home was being broken up.' His life seemed to fragment after that. 'I can hardly believe it when I think how it began,' Agnes said in retrospect. 'It was very difficult. It gradually became a terrible nightmare. He knew he had cancer.'" (BA453)

In a footnote Matossian writes that in a written note to her from Agnes in December 1997 that "Agnes Gorky explained that 'the reason [for removing the children] was to give Gorky and me time to rest and be alone together. Gorky was not well and very upset by the children's noise etc. We both missed them terribly.'" (BA538n11)

In Hayden Herrera's version of events the children were apparently back at the Glass House by the 17th. She quotes Mougouch (see below) in which Mougouch says that before leaving for her secret tryst with Matta on June 17th she arranged for a babysitter. When she returned she took the children to her parent's farm in Virginia. (HH586)

June 5/6, 1948: Matta visits the Gorkys. (MS356)

Although Hayden Herrera comments that "For years she [Agnes] had fended off Matta's flirtatiousness. Now his naughty-boy behavior began to attract her" in her section about Matta's visit in her biography of Gorky, Herrera notes one page later in the same book that there was nothing in Agnes' June 7th diary entry "to indicate any amorous relationship with Matta."

Hayden Herrera:

"A few days after the birthday party, Matta came to the Glass House for the weekend. Later he confessed that he had fallen in love with Mougouch [Agnes] on one of the many weekends that he spent at the Glass House. Perhaps it was that first weekend in June. After everyone had retired for the evening, Matta noticed that, because of its angle, the open window to Gorky and Mougouch's attic bedroom reflected their bed. As Matta told the story, he saw Mougouch's reflection reflected on the window of the floor below. While it is unlikely that any window opened in such a way that Matta could have seen via reflections up into Gorky and Mougouch's bedroom, it made a good story. Matta must have gone outside, stood in the grass, and looked up. He was smitten... After Matta's visit, her [Mougouch's] diary entry for June 7 says nothing to indicate any amorous relationship with Matta... And yet, within a few days, she had taken Matta as a lover." (HH584-5)

Agnes' diary entry for June 7th reveals that rather than being enamoured with Matta, she didn't trust him.

Agnes Gorky [diary entry dated June 7, 1948]:

"Matta was here this weekend & we enjoyed him - we talked a great deal about his magazine Instead & always reverted to his central theme the creation of a new myth - the word which will release a new flow of enthusiasm & energy - Gorky and I tried to make clear our feeling that these things are not consciously planned nor are they even apt to be recognized when they happen by any group of so-called intellectuals, consciously striving to hit the jackpot as it were - But as usual we were really talking on two planes none of us adhering to a single plane [...] It is Surrealism that Matta would supersede with a new reawakening of the same spirit of poetry...

... If only I felt more sure of myself - sure of what it is that I am opposing in Matta's effort. Certainly he is stimulating if only in this provocative way of stirring you to formulate your opposition. But then 9/10 of the disagreement arises from the difference in our lives, our attitudes. He lives almost as a public man. His great effort seems concentrated on solving or rather proving the validity of his own anguish in world terms - if he could spring the lock that hides the secret of our times... I feel sorry for him & wish in one way we could work with him - But I don't trust him... it is too often a very superficial enthusiasm - too quick his recognition - & his own desire for greatness could so easily blind him to the truth & lead him to embrace the easy superficial way." (MS357)

June 17, 1948: Agnes ["Mougouch"] has a secret rendezvous with Matta.

Agnes ["Mougouch"] later recalled that she "bolted on June 17, the morning after this horrid experience with Julien Levy and Gorky." (HH585) Gorky's art dealer, Julien Levy, had been visiting the Gorkys at the Glass House and had brought with him a bottle of whiskey. Gorky was not normally a drinker (and certainly not as much of a drinker as Julien) but on this occasion both men got drunk. After dinner they discussed what an artist's wife should be and compared an artist's wife to, among other things, a horse pulling a cart driven by the artist. The conversation made her so angry that she "left the room in tears" and the next day packed a suitcase and left.

Agnes:

"I packed a tiny suitcase. I told Gorky I was going away, but I didn't tell him where. I had a local girl who used to baby-sit for the children. I got her to come early and to leave when the children went to bed. I said to Gorky, 'I'm going away for a couple of days.' I said I'd be back on Sunday. After I left I rang up Matta. It was perhaps the worst thing I ever did, but I did it. The affair with Matta ruined my life in one zip. But if I'd stayed, Gorky's violence would probably have driven me away anyhow, as he got worse and worse.

I got into my car and drove down to the village. I rang up Matta and said: 'Do you really want to meet me somewhere? I'm going to be on the Saw Mill River Parkway at such and such a mileage.' And he was there. I went away with Matta for two days and came back and felt completely reborn... I told no one, but I don't know that Matta was discreet. I assumed he would be. Matta knew I did not want to leave Gorky, that I had no intention of continuing to see him alone. But I have been told by others that Matta was even boastful." (HH586)

Matta:

"She [Agnes] was brought up differently from Gorky. She was like a cousin to me. We spoke the same language. We were 'tweedy' and the others were 'oily.' Mougouch and I had the same education. Before Gorky became ill, they sometimes came to my house in Sneden's Landing. Our children were the same age. Gorky and Mougouch's daughters would come to Sneden's Landing and see my sons. But when Gorky was ill my place was not comfortable enough for him, and I would visit them. The relationship with Mougouch became very strong for her. She was fantastic with Gorky, because he was very ill and had to do - things to do with the colostomy. She was like a disciple to Gorky. She was very devoted to him... Gorky was sweet and fragile and moving. He had an inferiority complex." (HH588)

After spending two days with Matta, Agnes ["Mougouch"] returned to Gorky and took Maro and Natasha to her parent's farm, Crooked Run, in Virginia for their grandfather's birthday. (HH588)

June 26, 1948: Julien Levy crashes his car while driving Arshile Gorky home. (MS360)

Agnes and the children were still in Virginia at the time of the car crash. According to Matthew Spender, she went to Virginia in order to pick up their children who were staying with their grandparents. (MS360) According to Hayden Herrera, Agnes was actually taking the children to Virginia at that time, not picking them up. (HH588)

In Connecticut, Gorky and Julien had retired to Julien's home in Bridgewater after lunch with a psychoanalyst friend of Levy's who thought Gorky could benefit from analysis. When Levy was driving Gorky home, he hit a road post on Gorky's side and the car overturned. Levy had (according to his account) a broken collarbone. Gorky had a broken collarbone and two fractured vertebrae in his neck. He was put into traction at the New Milford Hospital. (MS361)

According to Levy, during "the morning just prior" to the accident, when Gorky was at Levy's property, Gorky had told him that he had read Agnes' diary and that she was leaving him. (MA288) Levy claimed that when he was later visiting Gorky in the hospital Gorky "secretly" said to him as Agnes, who was also in the room, was preparing to leave - "No word, Julien, please about her diary. I think we will try to forget that." (MA288) Hayden Herrera casts doubt on Levy's comments, noting that "What Gorky said to Levy about Mougouch's diary and what Levy wrote about what Gorky said probably have little basis in fact." (HH558)

Hayden Herrera:

"The writer B. Blake Levitt, who helped Levy prepare his memoir for publication, recently added a few details to this story in an article for the Litchfield County Times. Levitt remembered that, fearing a libel suit, he and Levy cut out a section of the manuscript that said Gorky had told Julien that he had read Mougouch's diary and that it contained 'details of her affair and intentions to divorce.' What Gorky said to Levy about Mougouch's diary and what Levy wrote about what Gorky said probably have little basis in fact. Mougouch says that her diary contained nothing about affairs or plans. 'I had never hidden my diary from Gorky. It was about my dreams and my own selfish troubles. Gorky was never interested.' In any case, Gorky's feeling of abandonment that accompanied his depression could have made him perceive himself as abandoned even if he wasn't. And Levy's memoir was affected by his anger at Mougouch over her liaison with Matta. Moreover, to assuage his own guilt at having caused Gorky's broken neck, he wanted to paint a picture of Mougouch as the woman who drove Gorky to despair." (HH588-9)

Agnes first heard of Gorky's accident from Kay (Sage) Tanguy who lived near the Gorkys in Connecticut. Kay rang Agnes in Virginia to tell her what happened and Agnes flew home. Matta met her at the airport.

Agnes:

"I was in Virginia not long when I had this telephone call from Kay Sage saying Gorky was in the hospital with a broken neck. I took a plane to New York. Matta picked me up at the airport and drove me to Connecticut. He left me at New Milford Hospital and went to wait at a cafe nearby." (HH592)

When Mougouch arrived at the hospital she was shocked by what she saw. In addition to his neck being broken Gorky's painting arm was "semiparalyzed."

Agnes:

"He was in traction and he was completely berserk. They had to set his collarbone but when he got back up he discovered that his right arm was completely awful. I guess the nerves of the right arm had gotten messed up somehow, and his arm was semiparalyzed. He couldn't lift it. So he saw this blackest despair. The nurses all said he was impossible: 'You'll have to take him home,' they said... He won't let us do anything to him.' They wanted to give him an enema. He refused... Gorky couldn't take it - this state. He couldn't bear being in traction with a colostomy..." (HH592)

According to Julien Levy an intern he spoke to at the hospital told him that "Every day he [Gorky] says to make way for crowds who will come to visit him. 'Make way for the throngs,' he says; his very words. And he says he is a famous genius... Throngs will come, he says, when they learn we keep him there, detain him on a rack of torture." (MS287)

Although the throngs failed to materialize, Gorky did have several visitors during his stay in the hospital. When Peter and Ebie Blume visited and saw the state he was in - his head was pulled back and weights had been applied to his body to stretch his neck and keep his vertebrae apart - Peter commented that he "looked like Christ in a crucifixion." When Margaret Osborn visited and saw his condition she "came away thinking, Gorky was crucified." (HH595) Julien Levy's wife, Muriel, would later say about Gorky, "To go through the path life took him, with all its pain, ordeals and nightmares... you'd have to be a saint to survive those things." (BAxv))

Mougouch left the hospital after Gorky fell asleep. She later recalled, "I went out and I suppose Matta drove me back to the house or to the railroad, where I'd left my car when I flew with the children to Virginia." (HH592) Matta returned to New York afterwards and Mougouch spent the night with the Tanguys. (HH593)

July 1948: Mark Rothko shows Harold Rosenberg his multiforms. (RO248)

Mark Rothko and his wife were renting a small house in East Hampton, Long Island during the first part of the summer - from approximately June 3 through most of July. (RO607n29) At the end of his stay he invited several people, including Harold Rosenberg to see his multiforms. Rosenberg later recalled "he [Rothko] trotted out about, oh maybe fifty paintings he had done that summer." Rosenberg thought they were "marvelous, it was just one of the most exciting visits to an artist's studio that I have ever had. He took out one painting after another and set them down. They were just absolutely terrific." (RO248)

July 1 - August 25, 1948: Willem de Kooning teaches at Black Mountain.

De Kooning got the job through the efforts of a friend he first met when working for the Eastman Brothers - Misha Reznikoff. Reznikoff knew the sculptor Peter Grippe and his wife Florence who ran the Atelier 17 printmaking studios in Greenwich Village. Reznikoff knew that de Kooning needed money and asked the Grippes if there was anything they could do for him. Joseph Albers, who was head of the art department at Black Mountain, was a friend of the Grippes and mentioned to them that he was having problems finding faculty for the summer session. Mark Tobey had agreed to teach painting but became ill and had to cancel the arrangement. Grippe recommended de Kooning for the job, adding that both John Cage and Merce Cunningham who were on the Black Mountain faculty, knew Bill and would vouch for him. After checking with Cage, Albers offered de Kooning the job. He would be paid $200 in salary in addition to room and board and train fare for both Bill and Elaine. De Kooning accepted the offer. Gus Falk later recalled what his class was like.

Gus Falk:

"... this little Dutchman comes in, says how do you do, and starts setting up a still-life. He spent about two hours setting up this simple, simple little still-life. Backing up and looking through the window of his hands seeing how it was, changing it a little bit, finally we were wondering what he was doing. Not talking much. Finally he stops and finishes it and he looks around and he says, 'Vell, ve're going to spend all summer looing at this ting. On one piece of paper or one canvas and we're going to look at it until we get it exactly the way it is. Then we're going to keep working on it until we kill it. And then we're going to keep working on it until it comes back on its own." (DK257)

Once they settled in, Elaine seemed to particularly enjoy the atmosphere of Black Mountain. According to Passlof she took "every class in the place" including those taught by Merce Cunningham who Elaine previously knew through Edwin Denby. When de Kooning's teaching stint came to an end, he returned to New York accompanied not by Elaine, but by Pat Passlof who de Kooning had offered to continue to teach. Elaine stayed on at the college, later recalling one of her last nights there with her husband:

From de Kooning: An American Master by Mark Stevens and Annalyn Swan:

"Not long before the summer came to an end, Elaine and de Kooning were at one of the Black Mountain parties when de Kooning, tired of the merriment, suggested a walk. 'I'm getting sick of crowds,' he joked. The two of them - who had gone to more parties in two months in the country, Elaine later said, than they had in the previous five years in the city - left the festivities and went into the darkness outside. 'After ten minutes on the moonlit road,' said Elaine, 'none of the lights from the school were visible to interfere with the vast, heavy, velvety blackness of the sky, nor did sounds of laughter and music penetrate the almost terrifying hush.' The two stood looking up at the sky, 'enveloped,' said Elaine, 'by the awesome multiplicity of stars.' It was a sight never seen in the city, where the reflected glare blanked out the stars and only a slice of sky was visible from a loft window. 'Let's get back to the party,' de Kooning said suddenly. 'The universe gives me the creeps.'" (DK263-4)

While at Black Mountain, de Kooning started work on Asheville which he would later complete in New York. (DK254/263)

July 5, 1948: Arshile Gorky returns home from hospital. (MS362)

At home Gorky became increasingly morose. Unable to use his right hand, he attempted to draw with is left hand. (HH597) Peter Blume recalled that Gorky "was depressed after the break of his neck for fear that he would not be able to paint... Everybody kept saying, 'Of course you're going to paint again.' But I don't know if that convinced him." (HH597)

Mougouch:

"After the accident, everything was awful as far as Gorky was concerned. Everything just collapsed. When he came home he had to wear his leather collar. He hated it. When he was lying down he'd take it off. His arm was not getting better. He was in misery about the arm." (HH595)

Gorky and Agnes continued to argue. Gorky was in extreme discomfort. He had to cope with the effects of earlier colostomy while wearing a traction collar around his neck. He slept in the guest room or on the sofa. On July 15, 1948 he and Mougouch had a massive argument. (MS362) After the argument, Gorky asked Agnes if she loved Matta. She said that she did but that she loved him more. The next morning she felt that they had had it out and things would be better from then on. (MS364)

July 16, 1948: Arshile Gorky confronts Matta. (MS364)

The day after their argument, the Gorkys drove to New York. Gorky had an appointment with Dr. Weiss and Agnes had an appointment with Jeanne Reynal's dermatologist to have a wart removed. Before she left she wrote a letter to Matta explaining the situation with Gorky and that Matta should stay away. (MS364)

The Gorkys stayed at Jeanne Reynal's house in New York. Once in the city Agnes and Gorky dropped the kids off at Reynal's home went to their doctor's appointments. After her appointment Agnes phoned Matta. She was horrified to hear that he had just had a run-in with Gorky. Gorky, after secretly making an arrangement to meet with Matta, had chased him through Central Park trying to beat him with his stick. According to Matta Gorky had eventually calmed down and Matta reassured him that Agnes did not intend to leave him. Gorky at one point apparently compared Matta to the Soviet Union and later in the conversation began to rant about Stalin - by which time Matta was convinced he was insane. Matta told Agnes to have a talk with Dr. Weiss about Gorky. After a discussion with Weiss she took the children and flew to Virginia, leaving Gorky alone in New York. (HH602)

Agnes:

"I told him [Dr. Weiss] everything. I told him I'd had a two-day fling and that Gorky had discovered it... he [Dr. Weiss] said 'I've been watching him and he's been going down under.' He said he had seen it in Gorky's painting. Gorky was 'sinking into darkness...' Gorky was insane... Dr. Weiss said, 'Yes, I found Gorky very disturbed. He'll beat you up. He'll kill you all. It's very dangerous and I have to save the lives I can save. I'm sending you to your mother's. I'm going to call up the airport and get you and the children tickets.'" (HH602-3)

July 17, 1948 (Saturday): Arshile Gorky roams the streets of New York. (MS367)

Still in New York, Gorky phoned the Schwabachers who invited him to visit for the weekend but he told them he wanted to return to Sherman. He told Ethel that he was very unhappy and that his marriage was at an end. Ethel became concerned and rang Mina Metzger who, like Ethel, had been a student of Gorky's and had remained in contact with him. Mina had apparently already spoken to Dr. Weiss and Gorky was to see a psychiatrist in three days, after the weekend. She suggested that someone accompany Gorky back to Connecticut if he insisted on going. Meanwhile, Agnes was attending an auction with her parents in Virginia. (MS367) She apparently rang Jeanne numerous times but was unable to get through. When she did finally reach her, Jeanne told her that Gorky had been wandering the streets.

In the evening, Gorky (carrying a small toy bird) knocked on the door of an old friend, Gaston de Havenon (at 7 East Eighth Street), but Gaston wasn't home so he went to Noguchi's studio who tried his best to calm him. Noguchi told Gaston later that Gorky had been looking for him and that he had with him a small papier-mache bird as a present which he'd left behind in Noguchi's studio. Although they looked for the bird later, it was never found. (MS367)

July 18, 1948: Agnes Gorky writes to the Schwabachers. (MS367/HH603-4)

Agnes ["Mougouch"] wrote to the Schwabachers from her parents farm in Virginia where she had taken the children - Crooked Run Farm.

Dear Ethel & Wolf

I am sure by now you must have heard something from Gorky and whatever it was it must have been a great shock to you both. I am sorry that I myself can tell you nothing that will lighten your so kind & generous hearts - but only add to the dread weight of this final disaster. That it must be final I know not only from my own heart by now wrung quite bloodless but from the advice of Doctor Weiss. There is everything & nothing to explain for the words look so cold & short & it has been a very long & passionate struggle which I can no longer make especially as there are two hopeful little girls involved...

Gorky's mental condition is serious, has been for several years and I have been dreadfully wong in trying to pretend otherwise... At the moment he is in no shape to make any decisions regarding the children nor do I know what we will be able to do with the future, even as to where we should live. I have written our tenant in the studio explaining the necessity of Gorky having it back, if for no other reason to try to establish a sense of continuity in his tormented world & later when I see how things go I must find a job & make a home for the girls... I think in a few days or a week I will take them up to Castine until I can come to some understanding with Gorky... I never conceived of life as easy & that if we failed it was because I had failed - a fatal case of inflation alas, for this thing is far beyond me now, and all his friends with all their warmth & affection can only help him if he can help himself.

Believe me, my heart has been totally engaged even to the exclusion of my instinctive nature and if I could have I would have spared him this but my love was not strong enough I guess.

I shall always be devoted to you & grateful beyond words & thank God I know you love him.

Agnes.

July 19, 1948: Arshile Gorky returns to Connecticut. (MS369)

Gorky had continued to roam the streets of Greenwich Village after Agnes took the children to Virginia.

Nouritza Matossian:

"The account of Gorky's last two days are confused... late at night, he wandered from the Village and found himself at 7th Avenue East, near the old Hotel Brevoort, where Gaston de Havenon lived. Gorky rang his bell... but there was no answer. He walked all all the way back down to the Village, to MacDougal Alley where Noguchi lived. They had often sat up all night, talking and sketching. He had not seen his friend for over a year, maybe longer. He stood before the door which opened on Noguchi's little courtyard, ringing the bell, calling his name from the street. 'Isaamu. Issaammu! Isaamuu!'

Noguchi later told de Havenon, 'I heard someone calling. I thought I was dreaming but then I realised it was a real voice. Isaamu, just like our friend.

He [Noguchi] got out of bed and went down the stairs to his courtyard. It was still dark, but he made out a grotesque silhouette on his doorstep. It was Gorky, with a collar around his neck, and in each hand he held a little cloth doll [which had belonged to his children], 'Old, dirty rag dolls,' Noguchi said. 'And tears were streaming down his face.'

Gorky held out the little dolls to him and said, 'This is all I have. This is all I have left!'

Noguchi was stunned. He took his friend up to the studio. In familiar surroundings, Gorky looked at Noguchi who had been close to him for years and sat with him though his black moods in the past. Noguchi was alarmed by his uncomprehending, fearful look. Gorky unburdened himself. His old friends had turned away from him. He had made a little gift, a paper bird for Gaston, but he wouldn't open the door. People who had pretended to be his friends were not his friends; they made fun of him; he had been betrayed; he felt he had been emasculated morally...

They talked for a long time. Gorky asked Noguchi to drive him up to Sherman, but Noguchi told Gorky to wait until morning... In the morning Gorky again asked Noguchi to take him home, but first he wanted to call on his doctor. Noguchi waited in his car. When Gorky returned from Dr. Weiss, he said to Noguchi, 'They want to do a lobotomy on me.' (BA467)

Noguchi drove Gorky back to Sherman, accompanied by Wilfredo Lam and his wife Helena, whom Gorky had met a year or so previously. In Sherman they rang Saul Schary who promised to bring Gorky some groceries and to keep on eye on him.

Hayden Herrera:

"Helena [Lam]... said that [Isamu] Noguchi called her and Wilfredo one morning to ask them to join him and Gorky on the drive to Sherman. Noguchi picked Gorky up and drove to Pierre Matisse's East Seventy-second Street apartment, where the Lams were staying that summer. 'When they arrived at our house, ' Helena recalled, 'Gorky told the doorman to ring and ask us to come to the window, as he did not want to come up. When we looked out we saw Gorky standing on the sidewalk, sad and dejected, constantly squeezing a small black rag-type doll in his hand. Wilfredo and I were perturbed by Gorky's looks but hoped that the drive with Noguchi and ourselves would animate him.' Gorky's right arm was stiff, she remembered, 'It hung down, he couldn't move it'...

In the car Gorky made an effort to talk about painting with Wilfredo, but mostly he was subdued. When they reached Sherman, he asked Noguchi to stop for a minute at the local store. He wanted to buy candy for Maro and Natasha. Helena went into the store with him and bought some chocolates for herself. When she tried to pay, Gorky would not let her. He gave her a dark look and said, 'Helena, what does it matter who pays?' Nothing matters anymore, soon all will be over anyway.'" (HH597-8)

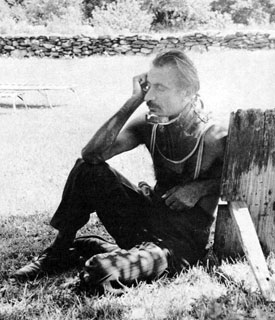

Once back in Sherman, Wilfredo Lam took photographs of Gorky in his traction device - just days before Gorky's death. (MA/HH468)

Gorky spent much of the time on the phone during the next two days in Connecticut, ringing his friends and telling them that his marriage was at an end, that Agnes had deserted him, saying that he had read her diaries. He tried to trace an Armenian friend who had been on the boat with him that brought him to America. He asked some of the people he rang for favours. Two friends who lived miles away were asked if they could drive over to see him immediately which they were unable to do. He asked Julien Levy if he could provide him with "a woman" who would help around the house. Other people he spoke to included Kay Sage, Lola Calas, Raoul Hague, Reuben Nakian. (MS369)

Then he rang Agnes. Relieved to hear his voice Agnes later recalled that she asked if she could return home and he mumbled incoherently saying he would "act like a man" and that he would "free" her. (MS370)

The evening of July 20, 1948: Saul Schary visits Arshile Gorky.

During that evening Gorky showed Schary a book on Leonardo da Vinci that Agnes had given him for his birthday. According to Hayden Herrera, "after Schary left, or perhaps even before, Gorky began drinking heavily" and "continued his telephone calls to old friends and acquaintances." One of the people he rang was Kay Sage. Sage had arranged for Gorky to have lunch with her and Dr. Allan Roos, a psychiatrist, the next day and Gorky was calling to cancel the appointment. She became concerned and rang Julien Levy who was equally concerned. It was in the middle of the night and too late for her to drive to Sherman so she rang Gorky's next door neighbour, Peter Blume, suggesting that maybe he could go over. Blume didn't go that night, but did visit the Glass House the following day. (HH609)

The morning of July 21, 1948: Saul Schary visits Gorky again.

The previous evening Schary had left his glasses at Gorky's home.

Hayden Herrera:

"... Schary called Gorky to ask if he could come and pick up a pair of distance glasses that he had taken off when they were looking at the Leonardo book the night before. Gorky said he would have them ready for him. Schary drove to the Glass House, entered by the screen door, which was always open, and found Gorky hunched over the telephone. 'Yes, my dear, ' Gorky said. 'No, my dear.' Then, 'good-bye, my dear,' and he hung up. 'He was in a very disturbed way when I got there. And he turned toward me, with my glasses in his hand, and said, 'Schary, Mougouch has left me. And my life is over. I'm not going to live anymore.' Schary delayed his departure as long as he could. He tried to persuade Gorky that he had everything to live for: his children; his painting. His work was beginning to sell. Gorky was unconvinced. 'Don't worry, Schary. I am going to act as a man does.' After an hour or so Gorky said, 'Schary, would you please leave. I have to do something.' Thinking that Gorky meant he had to attend to his bowels, Schary agreed to go. Gorky accompanied him out to his car. 'And I got in the car and he came around and picked up my hand, which was on the car, and he took it in both of his large hands, kissed it and said, 'Good-bye, Schary..." (HH609-10)

Having said good-bye to Schary, Gorky called Mougouch again... He told her he was going to take his bath. After that he would 'free her and free himself.' When she talks about these days, Mougouch's voice becomes constricted, almost as if her vocal cords cannot give sound to this memory: 'He told me, 'I'm going to kill myself. I'm going to hang myself.' I said, 'Don't. I'll come back. I am coming back.' He said, 'Don't come back. I've read your diary and I'm going to free you.' He said it quite nicely.' She repeated her offer to return to the Glass House, but Gorky abruptly hung up. Mougouch tried to call Gorky back, but he didn't answer.

Full of dread, she waited. She felt certain that Gorky would carry out his threat. 'I sat by the telephone and then Peter Blume rang. Gorky had hung himself.'" (HH610)

Late morning/afternoon July 21, 1948: Arshile Gorky commits suicide.

Sometime after Schary left Gorky's neighbours, the Blumes and the Cowleys went to the Glass House to look for Gorky. Peter Blume had been there earlier but had not found Gorky home and had rung Saul Schary to ask if he knew where he was. Kay Sage had meanwhile rung Muriel Cowley to ask if she could check on Gorky, telling her "Don't go alone." (HH611) After finding nobody there the Cowleys had gone over to the Blumes to find out if they knew anything. The two couples returned to the house to look for Gorky.

Peter Blume:

"Malcolm and I went up to the waterfall and the road sort of petered out and we had to stumble around in there. And we looked all over, thinking that he might possibly try to hang himself from one of the overhanging trees, because I thought that he had sort of a profound interest in the waterfall. And because it was so far removed from everything else, I thought this might be the place where he might choose to commit suicide. But he wasn't anywhere around. So we started wandering and came to a little road where the uranium prospector [from whom the Hebbelns had bought the property] had placed a stone crusher for construction. Gorky had two dogs, a dachshund and a huge dog as big as a horse. [The dogs belonged to the Hebbelns.] And when we saw this little dog barking as we came up, we knew this was where Gorky was...." (HH611)

Malcolm Cowley:

"We turned and followed the dog, which immediately stopped barking and trotted ahead of us. He led us to an old shed. The French would call it a hangar. That is, it was open on one side. And inside the shed, Gorky's body was hanging, looking like wax, his feet only a few inches from the ground. His shirt had slipped up and his pants had slipped down, and you could see the [colostomy] bandage around his abdomen." (HH612)

Peter Blume:

"... I saw... little dangling bits of rope around, hanging from the rafters... He had strung this clothesline over the rafters, had made a noose, and then stood on the box, just an ordinary box, which he kicked out from under him when he let himself down. And actually, when he was hanging, his feet could almost have touched the ground. He was so close because the rope, which was just a single clothesline, had become very much distended, quite stretched out by the weight of his body. There wasn't any double loop. It was just thrown over... Right next to the body was an old crate that a picture could have come in. Not a very big one, perhaps about 20 x 40 inches. And Gorky had written a note on that, 'Good-by my loves..." (HH612)

Malcolm Cowley recalled that the message said "Good-by all my loved." (HH613) During his lifetime Gorky had used the the term "beloveds" or "loveds" to refer to friends and family as well as his paintings. After the fire in his studio in Sherman on January 16, 1946, he had named two of his paintings Charred Beloved I and II. Was Gorky saying good-bye to his friends and family or to his work? Or to both? Mark Rothko would later comment about Gorky "I wonder if perhaps his love for art furnished him with his single greatest source of happiness. I believe it did." (RO267) Not being able to paint since his accident, Gorky was left without his "single greatest source of happiness." Although Matthew Spender noted in his biography of Gorky that the paralysis of his painting arm "gradually subsided," it is clear from Helena Lam's description of Gorky on July 19th that his arm was still a problem. According to Lam, it "hung down" as if "he couldn't move it." (HH597-8)

Peter Blume recalled that when he was looking for Gorky, he noticed a slashed painting on the easel in Gorky's studio. Had Gorky slashed the painting immediately prior to hanging himself? Agnes did not recall such a painting but she had not been to Gorky's studio in Sherman since their trip to New York on the 16th. Blume remembered the slashed painting as being light in color. (BA540n7/HH611)

For more on Arshile Gorky, type his name into the search engine and scroll down on the results page:

July 22, 1948: Arshile Gorky's obituary appears in The New York Times.

Gorky's obituary repeated various false claims that he had made during his life in regard to his past. He was not the cousin of Maxim Gorky and he had not been born in Russia.

After Gorky's death, five biographies were published about him. The first was Arshile Gorky by his ex-student and friend Ethel Schwabacher. Schwabacher's book, published in 1957, included a preface by Lloyd Goodrich and an introduction by Meyer Schapiro. In 1962 Harold Rosenberg brought out Arshile Gorky: The Man, the Time, the Idea. In 1998 Black Angel: A Life of Arshile Gorky by the Armenian writer Nouritza Matossian was published. A year later Matthew Spender's biography of the artist, From a High Place: A Life of Arshile Gorky came out. The latest biography, Arshile Gorky: His Life and Work by Hayden Herrera was published in 2003. Both Spender and Herrera had links to the Gorky family. Spender was married to Gorky's daughter Maro and Herrera's father was married to Gorky's wife, Agnes, after Gorky's death. In addition, Karlen Mooradian, the son of Gorky's sister Vartoosh, also published translations of Gorky's letters. While researching her Gorky biography, Nouritza Matossian discovered that many of the letters were fakes.

Nouritza Matossian:

"I was overjoyed to meet the only living person who had shared Gorky's childhood, his beloved sister Vartoosh Mooradian. In Chicago, this fierce old lady with tarnished, silver hair and her mother's dilated, dark eyes fished out old boxes of letters from under her bed... Together we deciphered his economically inverted characters. I had in mind the books edited by her son Karlen Mooradian, containing the published translations of Gorky's correspondence on wide-ranging topics from Armenia to Cubism to Surrealism. But there was no sign of those didactic letters, nor anything like them. When I mentioned that some must be missing, Vartoosh held up her transparent fingers to her face. 'I guarded these letters like my life,' she protested. 'They were my gods.' She insisted that there were no other letters. I was bewildered...

As the only person outside his family, and certainly the only writer, to be granted access to the original letters, I needed to work fast to discover the truth. A comparison led me to realise that twenty-nine of the letters to his family which Karlen had published in English were missing from Vartoosh's collection and could not be traced. As I studied the easy affectionate style of Gorky's writing in the original Armenian, full of news about the family and his longing to be with them, I came to a shocking conclusion. The missing letters were not Gorky's words at all. Karlen must have faked them and then inserted them among the genuine correspondence in this book. " (HHxiv)

Matossian was unable to ask Karlen about the letters because he died in 1990 - a year before his mother, Gorky's sister Vartoosh. While researching his biography on Gorky, Matthew Spender, confirmed Matossian's suspicions about some of the letters that Karlen had published.

Matthew Spender [married to Gorky's daughter, Maro]:

"Karlen Mooradian was the only son of Vartoosh, Gorky's younger sister. It was Karlen who had translated and published all of Gorky's letters to his mother, the largest single source of information about Gorky's thoughts on art. On the walls of the tiny apartment in Chicago where he and his mother lived their entire lives hung photos of himself in poses exactly like the poses that Gorky had assumed at the same age. Karlen never married. His whole adult life was spent in the shadow of his uncle.

Vartoosh survived Karlen by little more than a year. Through the kindness of the executors of their wills, Maro was eventually sent copies of the original letters from which Karlen had made his translations. Studying these documents with the help of two Armenian scholars, we came to the conclusion that many of Karlen's translations were figments of his own fantasy of what Gorky was, or what Gorky should have been. They were extensions of the sad, strange conviction which Vartoosh had wished upon him - that his own life was a continuation of her brother's." (MSxxii-xxiii)

About four months after Gorky's death Julien Levy held a memorial exhibition of his work. Art News reviewed the show in their December 1948 issue which prompted the following letter from Willem de Kooning which appeared in the January 1949 issue of the magazine. (De Kooning was teaching during the summer session at Black Mountain when Gorky died.)

Sir:

In a piece on Arshile Gorky's memorial show - and it was a very little piece indeed - it was mentioned that I was one of his influences. Now that is plain silly. When, about fifteen years ago, I walked into Arshile's studio for the first time, the atmosphere was so beautiful that I got a little dizzy and when I came to, I was bright enough to take the hint immediately. If the bookkeepers think it necessary continuously to make sure of where things and people come from, well then, I come from 36 Union Square [Gorky's studio]. It is incredible to me that other people live there now. I am glad that it is about impossible to get away from his powerful influence. As long as I keep it with myself I'll be doing all right. Sweet Arshile, bless your dear heart.

Willem de Kooning

September 1948: Jackson Pollock drawing in Partisan Review.

A company called County Homes ran a series of ads on the inside cover of Partisan Review. The series included work by both Pollock and Gottlieb. Pollock's drawing titled Drawing appeared in their advert that ran in the September 1948 issue. Under the reproduction of the drawing the company noted, "We asked Jackson Pollock to draw this picture to help tell PR readers what County Homes is doing about housing." (SG185) The drawing was a fully abstract work which could not possibly "help tell PR readers" anything about County Homes or housing.

c. September 1948: Charles Egan marries Betsy Duhrssen and has an affair with Elaine de Kooning. (DK271)

Egan and Duhrssen met on Martha's Vineyard in the summer while Elaine and Bill de Kooning were still at Black Mountain. When Egan proposed to her he confessed that there there was another woman he would always carry the torch for but who he could never possess. It became apparent to Duhrssen who Egan was talking about during their honeymoon when both Charles and his brother called her Elaine. Elaine was surprised to hear of Egan's marriage when she returned to New York from Black Mountain. Duhrssen recalled that "Elaine and Bill were living separately and at the time there were doubts about whether Elaine was still married to Bill." Elaine would often dine with Egan and his new wife. Betsy recalls, "She and Charlie would sit and have martinis while I was cooking, and she would discuss what he should do." After dinner Charlie would escort Elaine back to her Carmine Street apartment . Betsy recalled, "He'd say 'I'm going to take Elaine home now' and that's all I'd see of him until the next day." (DK271-272)

Betsy also recalled that during one party, both Charlie and Elaine went missing. Duhrssen "heard Bill yelling upstairs. Elaine and Charlie were locked in the bedroom and Bill was beating on the door... This was in front of everybody, of his friends." (DK273)

Bill tolerated Elaine's affairs because he would have his own one night stands. They lived apart at Black Mountain and continued to live apart after coming back to New York. Even if he wanted to divorce Elaine at this time, he would have been reticent - he was still not an American citizen and his marriage legitimised his position in the states. (DK275)

According to de Kooning biographers, Mark Stevens and Annalyn Swan, "In the late 1940s and '50s, Elaine even had affairs with de Kooning's two main critical champions, a brief fling with Harold Rosenberg, and a longer, more substantive relationship with Thomas Hess that extended well into the decade." (DK346) Willem, meanwhile "casually saw different women. A few represented liaisons of a night, two nights or a week. Occasionally, he would be seeing several women at once. In the early fifties, he set up a bell system at his studio to protect his privacy and sort out his girlfriends, giving each a different signal, such as one or two or three rings." (DK346)

Autumn 1948: The Club begins.

There is a dispute over whether The Club started in Autumn 1948 or 1949. Art writer Irving Sandler and the authors of the Pulitzer Prize winning biography, de Kooning: An American Master (NY: Alfred A. Knopf, 2006), Mark Stevens and Annalyn Swan claimed that The Club opened in October 1949. However, Philip Pavia, who found the venue for The Club at 39 East Eighth Street, said that it began in the fall of 1948, as the Abstract Expressionists outgrew the Waldorf Cafeteria.

Philip Pavia:

...in 1948... the Waldorf Cafeteria crowd, the Hofmann School and the Eight [sic] Street bunch... decided to rent a club room. The Waldorf was too small for our growing numbers, we were close to forty artists more or less, and the meetings were getting out of hand...

In 1948 I found a permanent place on Eighth Street, which was a block of empty lofts at the time. One by one different artists rented spaces there. We took a space between Stanley Hayter's print shop and Robert Motherwell's Subjects of the Artist School. However, the space would not be available until September 1st. Lewitin and I rented it from Sailors Snug Harbor Real Estate Corporation for $80 per moth We took it and we waited for our Club 'to be.'

Ibram and Ernestine Lassaw offered to have meetings at their loft to settle the problem of where to meet temporarily. The Club stated officially in the fall of 1948 at 39 East Eighth Street." (Philip Pavia, Club Without Walls, Selections from the Journals of Philip Pavia, ed. Natalie Edgar (NY: Midmarch Art Press, 2007), p. 48, 50, 53)

According to Irving Sandler, in A Sweeper-Up After Artists: A Memoir, The Club was formed as a result of a group of artists who met informally at Ibram Lassaw's studio in the "late fall" of 1949 "for the purpose of finding a meeting place." (IS27) The artists identified by Sandler who met at Lassaw's studio included Giorgio Cavallon, Peter Grippe, Franz Kline, Willem de Kooning, Landes Lewitin, Conrad Marca-Reilli, Phillip Pavia, Milton Resnick, Ad Reinhardt, James Rosati, Ludwig Sander, Joop Sanders, Jack Tworkov, art dealer Charles Egan, Elaine de Kooning and Mercedes Matter. Sandler later became the "manager" of The Club in 1956. (IS28)

According to Ibram Lassaw's daughter, "The quote from Irv Sandler... is not to be trusted. My mother says we never even met Irv Sandler until 1959 when my father gave him the opportunity to write about him for Three American Sculptors, Grove Press." (Denise Lassaw to Gary Comenas, "re: The Club," July 30, 2010)

The artists who met around Lassaw's kitchen table for the initial meeting about The Club was not the group that Sandler notes, according to Lassaw's daughter (after discussion with her mother):

Denise Lassaw:

Our dining table only seats about 6 people and it wasn't crowded. My mom remembers- Bill deK, Milton Resnick, Conrad Macarelli, Lewitan, Philip, and Ibram. The guys weren't thinking of being "charter members", they didn't even bother to take a picture, although my father had a camera and a dark room to develop film. They just wanted a place to sit and talk and not be bothered by the manager of the [Waldorf] cafeteria. they weren't thinking HISTORY. (Denise Lassaw to Gary Comenas, "re: The Club," July 30, 2010).

In regard to membership, Stevens and Swan claimed that "First, it was decreed that no women, communists, or homosexuals could be members of the Club, those three groups were deemed to be already too clubby, in an undesirable sense. (This rule was contested from the beginning, and later collapsed.)" (DK287) Stevens and Swan do not footnote their claim, however, so it is impossible to discover the source of it. It is not backed up by the published diaries of Philip Pavia.

From the diaries, conversations about membership revolved more around what type of artists would be welcome. Abstract artists and surrealists were okay but figurative artists were not particularly welcome.

Philip Pavia:

Our problem for many years was the induction of new members. A meeting for this purpose was like a review on art history and its prejudices:

"Let's keep the membership at he cafeteria level, working artists and no students... What about those strict geometry artists? The talk down to you like mothers-in-law, and never as equals.... No architects, they are absolutely colorblind... We should have a sprinkling of other artists besides painters and sculptors. Let's be generous and even include musicians... Let's include the Surrealists and their redcoat army... Let's go easy on letting the figurative artists in, because they're always talking about this cliché and that cliché. If you scratch them, they bleed art history... let some outsiders in...." (Philip Pavia, Club Without Walls, Selections from the Journals of Philip Pavia, ed. Natalie Edgar (NY: Midmarch Art Press, 2007), p. 56)

When The Club first started each member was given a key and could come and go as they pleased. Meetings were generally arranged by telephone on the "spur of the moment." Soon it became more formal, however - speakers were invited and discussion panels were prearranged. Roundtable discussions limited to members were held on Wednesdays until 1954 and lectures, symposiums and concerts took place on Fridays. Initially, guests were admitted for free, but later there was a charge of 50 cents for guests. Only coffee was served when The Club first opened.

Although Jackson Pollock was staying in New York for about three months from Thanksgiving 1949 onwards, he did not regularly attend the meetings at The Club. He did attend The Club once in the winter of 1950 but left before the lecture had finished. Harold Rosenberg would later say, "Jackson didn't like doing things with coffee." (JP201)

Eventually alcohol was introduced to the meetings - first a bottle of whiskey was supplied to "oil up" the panelists and, later, was served after the panel discussions, paid for by passing a basket. (IS30)

Elaine de Kooning:

... they would have these panels and after the panels they would pass the hat and buy liquor. And then everyone would have a very tiny amount, like half an inch of a paper cup. And they would have records of polkas which Philip Pavia liked, so everyone would dance. And that would go on for hours. It was a great deal of fun. After the panels there always was a party. I mean, it became very, very festive and people tried to come after the panel discussion was over, but Philip outwitted them. He simply made the panel discussions later and later. They were supposed to begin at 8:00, but he would wait until the audience came in, hoping the panel was over with, and then they'd be confronted with this speaker of the evening, whoever it was. (SE)

Autumn 1948: The Whitney's annual show of American art includes de Kooning's Mailbox. (DK265)

Autumn 1948: Jackson Pollock begins treatment for alcoholism. (PP322)

Pollock started seeing Dr. Edwin Heller, a general practitioner who had opened a clinic in East Hampton in 1947. The period of sobriety would last until the autumn of 1950. (JP190) It would be his longest period of sobriety as an adult.

Jackson and Lee Krasner visited his mother, Stella, in Connecticut over the Christmas holidays. On January 19, 1949 she wrote to Charles Pollock, "There was no drinking. We were all so happy... hope he will stay with it he says he wants to quit and went to Dr. on his own." According to Stella, The Dr. doesn't give him anything just talks to him." The doctor's widow would later say that her husband "didn't believe in substituting one drug for another. He treated Pollock with sympathy. When Lee Krasner asked Jackson how Dr. Heller had managed to cure him of his alcoholism when numerous doctors had not, Pollock replied, "He is an honest man. I can trust him." (JP189-90)

The following year, in mid-April 1949, Stella Pollock wrote to Charles after visiting Jackson in East Hampton: "Was out at Jack and Lee was so nice to be there and see them so happy and no drinking... he feels so much better says so they were getting ready to put in garden they have good soil Lee loves to dig in the dirt and she has green fingers. (PP323)

October 1948: The Subjects of the Artist School opens. (RO263)

The school was located in a loft in Greenwich Village. On Friday evenings a guest speaker was often invited to talk, such as Harold Rosenberg and John Cage. De Kooning made his first public statement about art in February 1949 at the school. (DK277)

According to Mark Rothko biographer, James E.B. Breslin, Clyfford Still had first presented his idea of opening a school to Mark Rothko when Still was visiting New York in April 1947. He also broached the subject with Robert Motherwell. After Still resigned from the California School of Fine Arts and moved to New York in spring 1948, discussions about the school continued and William Baziotes and David Hare were proposed as staff members. From Still's diary entries, the idea was to create "a center of free activity for imaginative effort" with a "group of painters, each visiting the center one afternoon a week, each an entity different from the others, each free to teach in whatever way he chose or free to stay away, every student free to work or remain away, attend every teacher's meetings or none." (RO263) By the end of the summer, however, Still had given up participating in the planning of the school and returned to San Francisco to teach again at the California School of the Fine Arts. Rothko Motherwell, Baziotes and Hare continued with the plan and rented a loft in Greenwich Village at 35 East 8th Street. It was during the time that they were renovating the loft that Mark Rothko met Bernard Reis. Robert Motherwell took Rothko along when he went to Reis's office to ask for $500 to buy stoves to heat the loft. (RO263)

Barnett Newman suggested the name of the school to emphasize the importance of subject matter in abstract art. (MH) Robert Motherwell later recalled "The title was Barney's [Barnett Newman] and I remember we all agreed that it was right because it made the point that our works did have subjects." According to Motherwell, the name "was meant to emphasize that our painting was not abstract, that it was full of subject matter." (RO263)

The school's catalogue noted that "The artists who have formed the school believe that receiving instruction in regularly scheduled courses from a single teacher is not necessarily the best spirit to advance creative work." (Unlike the nearby single-teacher, single theory Hans Hofmann's school which operated nearby.) Florence Weinstein recalled, "The idea was that you didn't get influenced by one artist." (RO264-265)

According to Motherwell, the school had three goals - "One to make a little money for the teachers; two, to enable students to interact with a variety of avant-garde artists; and three, to provide a meeting place for the avant-garde and its audience." (IS27)

Robert Motherwell:

Well, there was the school that Rothko, Baziotes and David Hare and I had together for a year. Then I had a school of my own for a year [the Robert Motherwell School of Fine Art]. But in both cases we didn't make enough except to pay the rent and the heat and so on....

Clyfford Still was originally to be one of the teachers [at The Subjects of the Artist school]. We had arranged it that each of us would teach one day so that, say Baziotes would teach on Mondays; Rothko Tuesdays; David, Wednesdays; I would teach Thursdays; and Still, Fridays. At the last moment, for reasons I've never known, Still dropped out and went back to California. So there was a blank day and to fill that blank day we began to invite other artists - de Kooning, Reinhardt, Harry Holtzman - I don't know who all - to come and instead of teaching to give a lecture in the evening. We were very anxious that the school not be doctrinaire, that those of us who were teaching be regarded as individuals, and that the students be regarded as individuals. Those Friday evenings, as they came to be called, became the magnet, the center, for everybody in New York who was interested in the avant garde to come to. Originally it was just for the school. Then people would call up and say, "Can we come, too?" And pretty soon we were renting a couple of hundred chairs and so on. We were so poor then that the pay for whoever gave the lecture was to be taken to dinner and given a bottle of his favorite liquor. In those days we all drank seventy-five cent sherry. If he wanted a bottle of Scotch or whatever it was we got it for him, and seven dollars was like seven hundred dollars now. Then that whole tradition went on and became the famous Club. But that was pure chance."

(SR)

[Note: Although Motherwell gives the impression that the Club evolved from the school none of the artists who started the school attended the formation meeting of the club in October 1949.]

[Note: In A Sweeper-Up After Artists: A Memoir, art writer Irving Sandler incorrectly states that the school was founded "in the fall of 1949." In discussions with Robert Motherwell and Mark Rothko about the school, Sandler noted that the school was "Clyfford Still's idea, proposed when they drove in Still's Jaguar to visit Motherwell in East Hampton." Sandler also incorrectly states that "The School closed after one semester." (IS26) The school actually ran for three terms, closing in the Spring of 1949.]

[Note: According to the Frey Norris Gallery's Wolfgang Paalen chronology, in 1948 Paalen spent "November and December in New York with Motherwell in East Hampton to discuss the foundation of a new art school with Rothko and Clifford Still." The school had already opened by that time.

[Note: the Hackett Freedman Robert Motherwell chronology refers to the school as "Subject of the Artists" rather than "Subjects of the Artist."]

October 1948: Philip Guston travels to Italy.

Guston had won the Prix de Rome. He stayed in Italy for about a year while his wife and daughter stayed in Woodstock, moving from rural Maverick Road to Orchard Lane in Woodstock. (MM39) Guston later recalled "It was thrilling to go to Arezzo or Orvieto for the first time. "I went to Arezzo many times, and to Florence. Seeing the frescoes, the Uffizi in Florence, and Siena excited and exhausted me." (DA82)

Only a few drawings from his trip remain. Although Guston painted sporadically during the trip, he did do a lot of drawings in Rome but didn't keep them. A few drawings that he did on Ischia (where he had gone "to escape the oppression of the masters") exist. He also visited to Spain and France.

October 10, 1948: Mark Rothko's mother dies. (RO265)

Rothko's mother had suffered an extended illness and her death had been expected. Robert Motherwell recalled, "The death of his mother is the only personal thing he [Rothko] talked to me about at length. He became obsessed over whether or not to go back to Portland." (RO265) Rothko stayed in New York.

The painter Ben Dienes recalled that after the death of Dienes' mother, Rothko told him "he knew how I felt because when his mother died he stopped painting, and he wrote a novel. He didn't paint, he said for a year or more." (RO266) Rothko also told Alfred Jensen that after his mother's death he "wrote a book which took him two years to complete." (No book exists and if Rothko did stop painting it wasn't for a very long period.)

Toward the end of the autumn session of the The Subjects of the Artist School, Rothko withdrew from active participation in the school. He wrote to Clyfford Still that he had experienced a "minor breakdown." Motherwell also recalled that Rothko was "clinically depressed" in late 1948 but that it had nothing to do with the school. (RO265)

October 11, 1948: Life clarifies art.

Life magazine held "A Life Round Table on Modern Art" with fifteen "distinguished critics and connoisseurs" which it reported under the title "Fifteen Distinguished Critics and Connoisseurs Undertake to Clarify the Strange Art of Today." Life asked "Is modern art, considered as a whole, a good or bad development? That is to say, is it something that responsible people can support or may they neglect it as a minor and impermanent phase of culture?" (SG187)

Participants included Aldous Huxley, Georges Duthuit, Meyer Schapiro, James Johnson Sweeney, James Thrall Soby, Sir Leigh Ashton, Clement Greenberg and Francis Henry Taylor.

The article was more than 16 pages long. The discussion focused primarily on European art, particularly Picasso, Matisse, Miró, Dalí, and Rouault, but also included illustrations of work by what it referred to as five "young extremists" - Willem de Kooning (Painting), Jackson Pollock (Cathedral), Adolph Gottlieb (Vigil), William Baziotes (The Dwarf), and Theodoros Stamos (Sounds in the Rock). Of de Kooning's painting, Clement Greenberg said, "The emotion in that picture reminds me of all emotion. It is like a Beethoven quartet where you can't specify what the emotion is but are profoundly stirred nevertheless." (DK266)

About Pollock's painting, Sir Leigh Ashton (director of the Victoria and Albert Museum in London) commented that it was "exquisite in tone and quality. It would make a most enchanting printed silk." Aldous Huxley thought the painting raised "a question of why it stops when it does. The artist could go forever... It seems to me like a panel for wallpaper which is repeated indefinitely about the wall." A. Hyatt Mayor, curator of prints at the Metropolitan Museum of Art said, "I suspect any picture I think I could have made myself." A professor of philosophy at Yale, Theodore Green, thought it was "a pleasant design for a necktie." (JP187)

October 25, 1948: André Breton excommunicates Matta.

Near the end of the year Breton sent members of the Surrealist group that cantered around him a notice headed "Decisions." The first decision dated October 25, 1948 excluded Matta from the group for "moral ignominy and intellectual disqualification." Although Matta had tried to excuse the fact that he had slept with Gorky's wife by saying his action was commensurate with Surrealist principles - after all Breton, himself, had had an affair with Elisa Claro while still married to Jacqueline Lamba - Breton still blamed Matta for contributing to Gorky's suicide. The second decision, dated November 8, 1948 expelled Victor Brauner from Breton's group as Braun had refused to condemn Matta. (SS410)

October 26 - November 20, 1948: Jeanne Reynal, Mosaics exhibition at the Julien Levy Gallery. (MA312)

November 2, 1948: Harry Truman is re-elected President.

The re-election of Harry Truman as President of the United States was a surprise to the press who had predicted that Dewey would be elected. Truman's Freedom Train campaign helped with his re-election as did his constant warnings about Russia and Communism. A vote for Truman became a vote against Communism. The fear factor worked in his favour. A poll conducted by the National Opinion Research Center in March noted that 73% of those question thought that there would be a world war within 25 years compared with 41 percent in 1946 (SG168)

November 16 - December 4, 1948: "Gorky" at the Julien Levy Gallery. (MA312)

The show included eight paintings. The exhibition brochure listed the following works: White Abstraction (1934), Garden in Sochi (1941), The Pirate (listed as 1945 but actually painted 1942-1943), Delicate Game (1946), Good Hope Road (1945), Impatience (listed 1946 but actually 1945), Soft Night (listed 1948 but actually 1947) and Sculptured Head (1932). Also included were numerous drawings. (HH713n624)

Sam Hunter reviewed the show for The New York Times. Hunter had given a bad review of Gorky's earlier show at Levy's gallery. This time he wrote, "Altogether the impression is of an extraordinarily delicate, tactile talent that had blossomed to full intensity." Clement Greenberg (who loaned a drawing by Gorky to the exhibition) wrote in the December 11, 1948 issue of The Nation, "American art cannot afford Gorky's death, and it is doubly unfortunate that it came at a time when he was beginning to realize the fullness of his gifts..." Henry McBride, wrote in the Sun that the "effect of these highly stylized, sumptuous paintings upon the observer now is accusatory, naturally. One asks oneself why this had to be, why quicker help could not have been proffered, for it is evident the man had great talent and equally certain that a vast amount of anguish preceded the suicide." (HH624)

c. 1948/49: Willem de Kooning meets Mary Abbott.

David Hare introduced Mary to Bill on the street in approximately 1948/1949. According to de Kooning biographers, Mark Stevens and Annalyn Swan, it was "in the period when the Fourth Avenue studio was de Kooning's cave - not long after his separation from Elaine, when he was painting the black-and-whites and then Woman I." De Kooning's affair with Abbott continued intermittently until the mid-fifties and they remained friends after they stopped being lovers. (DK320-1)

Mary Abbott:

[De Kooning] wasn't gallant, not the pulling-out chairs kind of manners. But pleasant, polite... He was brighter than the others were, and quieter about it. Didn't knock you down the way Pollock did, but he was very much a man... I didn't like Pollock that much. When he was sober he didn't talk, and when he was drunk Bill had to keep pulling him off me. One evening I was at a dinner of the Rosenbergs' and I was smoking and I offered one to Pollock. 'Would you like one of these?' And he said, very pretentiously, 'I only smoke canvas.'" (DK322)

December 1948: "The Sublime is Now" by Barnett Newman appears in The Tiger's Eye.

Barnett Newman responded to the question "What is sublime in art?" by writing "I believe that here in America, some of us, free from the weight of European culture, are finding the answer, by completely denying that art has any concern with the problem of beauty and where to find it." (MH)